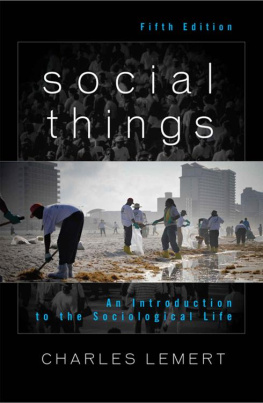

First edition 1995

Second edition 2004

First published 1995 by Paradigm Publishers

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1995, 2004 by Charles Lemert

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Cover art: Mistress and Maid by Vermeer. Copyright The Frick Collection, New York. Discussion of the painting in relation to the subject of this book appears at the beginning of . Ornament used with chapter titles is of Bangba origin.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-012-0 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-59451-013-7 (pbk)

T HE AUDACITY THAT JUSTIFIES a new edition of any book, even one not quite a decade old, puts the author of such a thing at the risk of repealing reticence too brazenly, thus overdoing what previously had seemed a good thing. Still, every once in a while, events beyond a books original concerns come along to sweep it into a new time where audacity yields immodestly to conviction.

I was in fact surprised by the question most frequently asked me by those who had heard of, but not read, Sociology After the Crisis. What crisis? The book appeared in 1995 and had been written in the years just before that. Looking backward, Im all the more amazed that, whatever the confusion aroused by the word Sociology, in the mid-1990s a title referring to a crisis would not promote more conviction. On second thought, the problem may have been with the word after, which allows the possibility that the crisis in question had passed. The fault is mine, but not all mine.

By 1992, just when Bill Clinton came on the global scene, many of us who at the time were inclined to think of the world as in crisis had been lulled into the naive expectation that social things, here and abroad, might get betterin principle if not in immediate fact. After the three terms of the Reagan-Bush administrations, the appearance of an American president who was both an enchanting communicator and brilliantly informed as to social policy seemed more than we of the indefinite left could have hoped to see again in this world. Not even the stunning victory of the right wing in the 1994 U.S. congressional elections was enough to dampen the spirits. Whereas the other side took hope from their long-dreamt-of victory over communism (not to mention a few wars here and there that seemed to purge America of the Vietnam syndrome), on the left the faithful took their relief from Clintons political outwittings of the conservatives and the steady improvement in the economy. Liberals at heart tend to forget their lessons. In the 1990s it was the lesson of the 1980s that obscene sums of new wealth flowed unevenly to the few on the upper floors of buildings before which, on the ground, doormen kept watch, greeting us in languages we could not understand.

Ours was a foolish, if honest, mistake, one that in retrospect had little to do with this or that complaint we might have against Bill Clintons and other third-way political strategiesnotably in the U.K. those of Tony Blair, which are largely inspired and thought-through, if not exactly invented, by Tony Giddens. A near decade ago we who did not quite see what the underlying crisis was, or how it was developing before our eyes, were simply looking in the wrong place. Wed have done better to look more closely to those of our acquaintances who for years had been warning of the global crisis in the capitalist world systemmost notably Immanuel Wallerstein, among others (many influenced by him). Put all too simply, for Sociologists to choose between Giddens and Wallerstein, the excellence of their works aside, is to choose between wishing the world were better than it is and realizing that it is what it is, for better or worse. Third-way politics holds out the hope that, though transformed, the world might be rearranged to meet the crisis. By contrast, a deep structural stock-taking of the capitalist world system leads by various paths to the realization that the world as it has been for a good half-millennium will sooner or a later come to a turning pointa realization which just happens to be the strict meaning of the word crisis.

It is not necessaryin fact it would be foolishto take sides too assuredly in this debate, which I so gawkily reduce to that between, on the one hand, a radical faith that the modern system, while shaken, is still workable and, on the other, a radical skepticism that the modern system, while powerful in all externally visible ways, has come at long last upon a crisis that, appearances notwithstanding, it may not endure. Indeed, this is not a debate between Giddens and Wallerstein, who do not regularly engage each other. It is, rather, a debate that is everywhere prominent among serious people of high or low station, in and out of academic Sociology, in and out of politics. It is in its way the debate of a lifetime for most of us still breathinga fact that comes as quite a shock to those of my generation, who arrived at what adult lives we have in the belief that the gloriously revolutionary 1960s were our defining moment. As it happens, the 1960s turned out to be no more than a prelude at most a beginningto the crisis now so evidently at hand that only the incautious would dare to deny it, even if, whatever they say for public consumption, they have not the least clue as to where the turnings will take us.

One of the more disputatious of the reviewers of the first edition of Sociology After the Crisis was a well-known Sociologist who took me for task for, in his view, my not knowing when the twentieth century began and the nineteenth century ended. Since the reviewer was clearly disappointed in me for the trouble I tried to make for the brand of Sociology he practices, I paid the complaint little mind save to thank him for the honor he did me in reading the book. Now, I think he had a point, though a point I do not buy. It is true that, like my betters in social history and other fields, I do not believe that centuries are strictly calendrical. Wallerstein codified the idea of the long sixteenth century; Giovanni Arrighi added the long twentieth century. I agree with Arrighi that the twentieth century did not begin any time close by the year 1900, but, rather than putting it at the long depression of 1873, I would shorten the twentieth century to beginning with the Great War of 1914. The nineteenth century collapsed not with the depression of 1873-1896 but with the war that solved nothing and contributed to the depression of 1929-1945. The war of 1914 dealt the liberal dream of modern progress the first of a series of body blows that came one upon another until 1990, when another series of events moved with unusual speed to put the very idea of a world, much less of a new world order, in a quandarythe end of the Cold War, the emergence of the American hegemony, the vulnerability of the American hegemony, the worsening of economic and health prospects for the worlds most poor, the brightening of world prospects in the new technologies of communication that began to encourage small businesses and not-so-small resistances to the tide of core dominance, and the impossible-to-explain social thing we now call globalization.

An imprint edited by Charles Lemert

An imprint edited by Charles Lemert