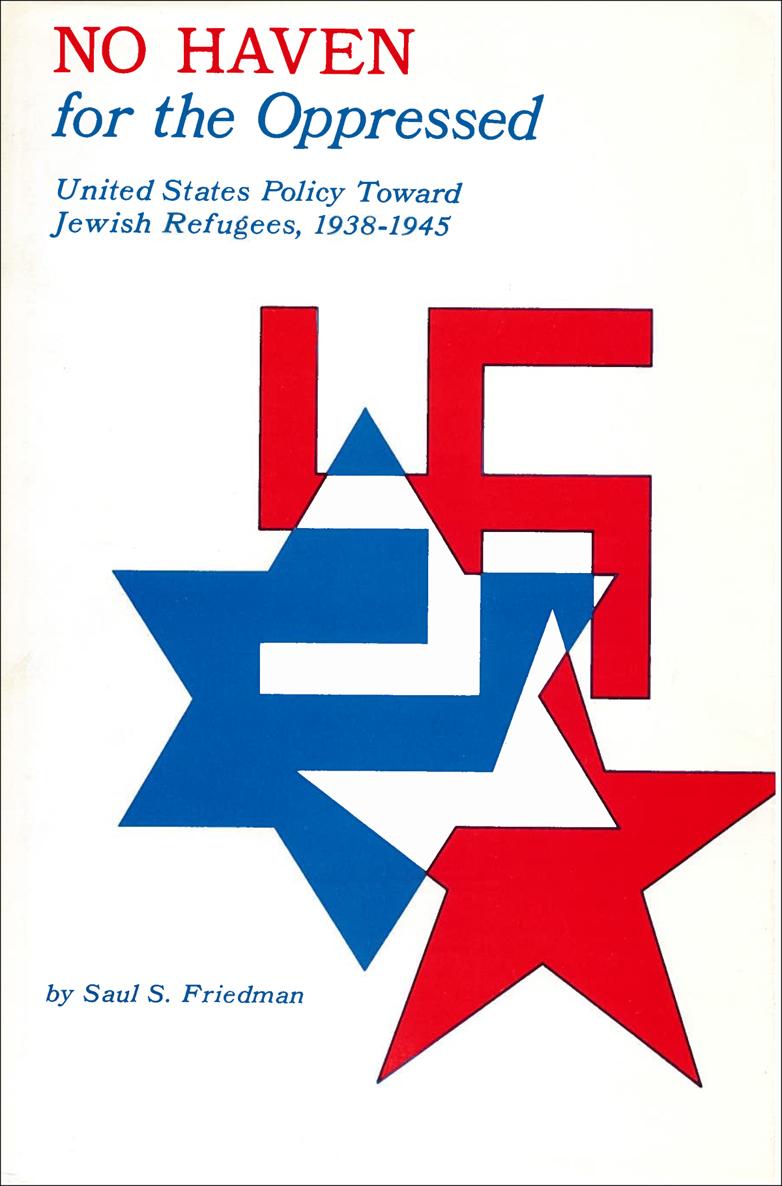

NO HAVEN

for the Oppressed

United States Policy Toward Jewish Refugees,

1938-1945

by Saul S. Friedman

YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY

Copyright 1973 by Wayne State University Press,

Detroit, Michigan 48202.

All material in this work, except as identified below, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/.

Excerpts from Arthur Millers Incident at Vichy formerly copyrighted 1964 to Penguin Publishing Group now copyrighted to Penguin Random House.

All material not licensed under a Creative Commons license is all rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the copyright owner to use this material.

Published simultaneously in Canada

by the Copp Clark Publishing Company

517 Wellington Street, West

Toronto 2B, Canada .

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Friedman, Saul S 1937

No haven for the oppressed.

Originally presented as the authors thesis, Ohio State University.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Refugees, Jewish. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945) 3. United StatesEmigration and immigration. 4. Jews in the United StatesPolitical and social conditions. I. Title.

D810.J4F75 1973 940.53159 72-2271

ISBN 978-0-8143-4373-9 (paperback); 978-0-8143-4374-6 (ebook)

Publication of this book was assisted by the

American Council of Learned Societies under a grant

from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

The publication of this volume in a freely accessible digital format has been made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation through their Humanities Open Book Program.

http://wsupress.wayne.edu/

Contents

Preface

T his manuscript represents the product of twelve years of research into the complicity of the Western democracies in what has popularly been termed the Holocaust, the slaughter of European Jewry in World War II. Several readings of Malcolm Hays Europe and the Jews generated intense discussions on this subject with an elder brother, Norman, while we were both students at Kent State University. Normans death in 1964 served as the motivation for a short research paper for Foster Rhea Dulles of Ohio State University on the wartime Anglo-American Conference on Refugees at Bermuda. The anguish of that research was the germinal of this paper.

My investigations of the Jewish refugee question have since been guided and expanded by Professors Robert Chazan, John Burnham, Harry Coles and Robert Bremner of Ohio State University. I am, however, especially indebted to Professor Marvin Zahniser, who took on an unknown student several years ago and guided him through the difficult days of general examinations, research grants, and the final editorial winnowing. Because of the excellent advice and direction given me by these scholars, I hope that this book constitutes a synthesis of American social, diplomatic, and minority history for the period 19381945.

In approaching such a difficult subject I have also been generously aided by a number of government historians and private archivists, including Miriam Leikind of Rabbi Silvers Temple in Cleveland, Ezekiel Lipshutz and Mrs. D. Abramowicz of YIVO, Hester Groves of the American Friends Service Committee, Robert Shosteck of the National Bnai Brith Headquarters in Washington, Richard Ploch, curator of rare books and special collections at Brandeis University, Dorothy Brown, professor at Georgetown University, Arthur G. Kogan, chief of the research guidance and review division of the Historical Office of the Department of State, Dean Allerd of the Office of Naval History, Thomas Hohmann of the Modern Military Records Division, and numerous unnamed persons in the National Archives, the Library of Congress, the Roosevelt Library at Hyde Park, the American Jewish Archives at Hebrew Union College, the Cleveland Public Library, and the Ohio State University who made my travels and studies less trying.

I am, moreover, indebted to those persons, at one time intimately involved in the decision-making processes of refugee questions, who have given freely of their time to answer questions related to this dissertation. Among them I wish to thank Harold Willis Dodds of Princeton University, who added valuable insight into the Bermuda conference; Lillie Shultz, Leona Duckler, and Richard Cohn of the American Jewish Congress, who broadened my understanding of Rabbi Stephen Wise; former presidential adviser Benjamin Cohen, I. S. Kenen of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, and Helen Eckerson, chief of the statistical section of the Department of Immigration and Naturalization.

But most of all, I wish to express my gratitude to my wife, Nancy, who tolerated the painful seizures of creativity and revision and encouraged me to continue with this project, which is dedicated to the oppressed children of all races and of all time.

S. S. F.

Introduction

I n the spring of 1941, when the United States was not yet formally embroiled in World War II and when it was still possible to rescue Europes persecuted Jews from Vichy France, Isaac Chomski, a doctor representing the OSE (Jewish Health Protection Society), the American Joint Distribution Committee, Secours Suisse (Swiss Aid), and HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) was placed in charge of 111 child refugees at the local Quaker relief office in Marseilles.* All but five of the children, whose ages ranged from eight to fifteen, were Jewish. Each carried a small, untidy bundle or a battered valise which held belongings remaining after wanderings in two or three different lands. Each child also wore a white numbered card about his neck, a card which read Father died in concentration camp at Buchenwald, Mother died in French internment camp at Gurs, Parents sent to Lublin, or simply Parents unknown.

Throughout the 500-mile train ride which carried the group on its way to the Spanish border and its ultimate destination, the S.S. Mouzinho, docked in Lisbon harbor, Chomski was struck by the solemnity of the children, their stoic acceptance of the meager food provisions, and their unlaughing silence as they watched a host of French university townsNmes, Montpellier, Toulouse, Tarbespass by. Only rarely did a child volunteer to speak with the doctor, and this conversation was generally followed by a tearful breakdown as the young refugee confided his fears of going to America, where he had no one.

On Sunday morning as the train neared the small provincial town of Oloron, thirty miles from the Spanish border in the department of Basses-Pyrenees, Chomski noted a transformation in the children. Awake even before dawn, they were in a festive mood, for many hoped to glimpse their parents for one last time this day. The children knew that close to Oloron was Gurs, the notorious French concentration camp where 10,000 Jewish refugees were living under the most primitive conditions. Originally constructed to house 3,000 Spanish Loyalist refugees, Gurs had been converted into a detention camp for German nationals (including Jewish refugees) by the French government in 1939. By 1941 it was serving as a deportation center to the East. Thirty persons died of hunger, exposure, or disease in Gurs each day, but this did not dampen the enthusiasm of Chomskis charges, who hoped that the prisoners would be released for a few moments to meet the train. Klaus, a boy from Germany, showed Chomski a photograph of his father. Tall, stately, his World War I German officers uniform bedecked with medals, the father was one of many still detained in Gurs.