Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2013 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53544-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Qualitative research in social work / edited by Anne E. Fortune, William J. Reid, Robert L. Miller, Jr.2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16138-1 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-231-16139-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-231-53544-1 (ebook)

1. Social serviceResearchMethodology. 2. Qualitative research.

I. Fortune, Anne E., 1945 II. Reid, William James, 1928 III. Miller, Robert L., Jr.

HV11.Q28 2012

361.3072dc23

2012036492

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

James W. Drisko

Frederic G. Reamer

Robert L. Miller, Jr.

James W. Drisko

Jane F. Gilgun

Roberta G. Sands

Catherine Kohler Riessman

Lesley Green Rennis, Lourdes Hernndez-Cordero, Kjersti Schmitz, and Mindy Thompson Fullilove

Shirley J. Jones, Robert L. Miller, Jr., and Irene Luckey

Judy L. Postmus

Raymie H. Wayne

James W. Drisko

Henry Vandenburgh and Nancy Claiborne

Ian Shaw

Ralph F. Field

Barry J. Ackerson

Timothy Page

Laura Frame

Julanne Colvin

Toni Naccarato and Liliana Hernandez

Julie S. Abramson and Terry Mizrahi

An increasing problem in many countries is the aging of the population, necessitating family caregiving that may pose serious burdens on the caregiving individuals. How should a researcher approach the burdens and strategies of caregiving? Here are two examples:

EXAMPLE 1:

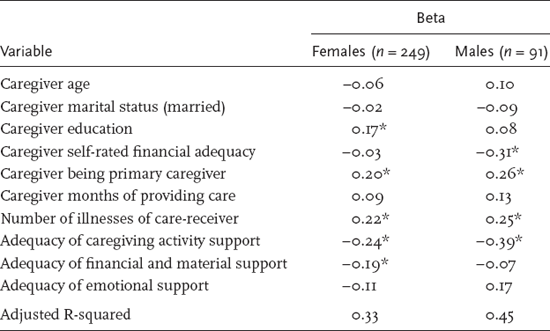

Lai and Thompson (2011) contacted 340 family members who cared for an elderly person. They conducted a telephone interview with each family member and gave them a structured questionnaire that included measures of caregiving burden, demographics, and social support. They used statistical methods to assess the impact of perceived adequacy of social support on the caregiving burden among male and female caregivers; that is, did caregivers who thought they received more support feel less of a burden? Part of the results of their multiple regressions are included in table 1.

The authors conclude: Perceived adequacy of social support was the most important correlate of caregiving burden for female caregivers and the second most important correlate of caregiving burden for male caregivers. For both male and female caregivers, the perceived adequacy of social support variables accounted for a larger proportion of the variance of caregiving burden than did the health of the care receivers. (2011:104).

Table 1 Portion of Multiple Regression, Predictors of Caregiving Burden

Table adapted from: Lai, D. W. L. and C. Thomson (2011). The impact of perceived adequacy of social support on caregiving burden of family caregivers. Families in Society, 92(1):99106.

*p .05

EXAMPLE 2:

Thornton and Hopp (2011) interviewed seven adult daughters who were caring for their parents with heart failure, using four open-ended questions about the illness, the most challenging thing about caregiving, assistance with caregiving, and what might improve their caregiving. They used a phenomenological approach and several steps of coding to analyze themes (caregiving stress and caregiver coping strategies). Here is part of what they had to say about valuing the caregiver role (a subtheme of caregiver coping strategies):

Several daughters reported receiving recognition from others in their community for their caregiving. This recognition was very important to the caregivers and seemed to help sustain them in their difficult vocation. As one caregiver explained, Theres a lot of people with kids and they be telling her, I wish I had your daughter for a daughter, because I take care of my mother. Valuing the caregiving role, evidenced by reflecting on caregiving qualities, identifying caregiving benefits, and accepting community validation for caregiving, helped the caregivers cope with the stressors of their work (Thornton and Hopp 2011:214).

Although the two examples deal with similar topics, they represent very different approaches to social work research. Example 1 is, of course, a quantitative research study. It relies on standardized questionnaires with the assumption that the questions have the same meaning for everyone, involves a fairly large number of participants, uses statistics to look at the relationship between social support and caregiving burden, and enlists probability to determine the likelihood of a true relationship. Example 2 is a qualitative research study. It relies on a set of open-ended stimulus questions, queries a small number of participants but involves in-depth questions about the topic, and determines participants key themes through the researchers interpretation using a systematic multi-level coding procedure. Instead of statistics, it uses the participants own words to illustrate and validate the themes.

Example 1, the quantitative study, can give the relation between social support and caregiving burden for the hypothetical average caregiver. It cannot tell what that support looks like nor how an individual felt if she did or did not get the support she expected. Example 2, the qualitative study, can determine how the women perceived the support, what it meant to them, and in this case, what type of support was useful. In this particular study, however, whether support increased or decreased the caregiver burden cannot be determined.

This book is about qualitative research methodology in social work, example 2. The first edition of Edmund Sherman and William J. Reids (1994) Qualitative Research in Social Work was one of the earliest attempts to present qualitative methods from a social work point of view. At a time of epistemological debates but not much actual research, it included not only methodology but exemplary social work research and commentaries from most of the seminal researchers of the time. It quickly became an essential text for those learning qualitative methodologies.

Qualitative methodology in social work has evolved rapidly since 1994. In 1998, Deborah Padgett completed the first edition of her qualitative text, and in 2008, the second. Ian Shaw and Nick Gould (2001) also published a qualitative textbook. In 2002, Ian Shaw and Roy Ruckdeschel launched the international journal,