Whitehall Paper 79

The Permanent Crisis

Irans Nuclear Trajectory

Shashank Joshi

www.rusi.org

Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies

The Permanent Crisis: Irans Nuclear Trajectory

Shashank Joshi

First published 2012

Whitehall Papers series

Series Editor: Professor Malcolm Chalmers

Editors: Adrian Johnson and Ashlee Godwin

RUSI is a Registered Charity (No. 210639)

ISBN 978-0-415-83256-4

Published on behalf of the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies

by

Routledge Journals, an imprint of Taylor & Francis, 4 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon OX14 4RN

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Please send subscription orders to:

USA/Canada: Taylor & Francis Inc., Journals Department, 325 Chestnut Street, 8th Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19106, USA

UK/Rest of World: Routledge Journals, T&F Customer Services, T&F Informa UK Ltd, Sheepen Place, Colchester, Essex CO3 3LP, UK

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Contents

Shashank Joshi is a Research Fellow at RUSI and a doctoral student of international relations at Harvard Universitys Department of Government. He specialises in the international security of South Asia and the Middle East. He has published peer-reviewed work in academic journals, commented on international affairs for radio and television, and is a regular contributor to newspapers including the New York Times, Financial Times, Daily Telegraph, Guardian, Hindu and Times of India.

Shashank holds Master's degrees from Cambridge and Harvard, and previously graduated with a Starred First in politics and economics from Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge University. During 2007-08, he was a Kennedy Scholar from Britain to the United States.

He has taught as a supervisor and teaching fellow at both Cambridge and Harvard. He has also worked for the National Democratic Institute in Moscow on electoral analysis and democratic training projects, Citigroup in New York in their regulatory reporting division, and in RUSIs Asia Programme on India and global security issues. He is a graduate of the Columbia-Cornell Summer Workshop on the Analysis of Military Operations and Strategy.

His recent publications include Indias Military Instrument: A Doctrine Stillborn, Journal of Strategic Studies (forthcoming, 2013); Transition from Assad, in Syria Crisis Briefing: A Collision Course for Intervention, RUSI Briefing Paper, 25 July 2012; China-India Relations: Awkward Ascents, Orbis (Fall 2011); Reflections on the Arab Revolutions: Order, Democracy, and Western Policy, RUSI Journal (Vol. 156, No. 2, April 2011); China, India and the Whole Set-Up and Balance of the World, STAIR: St. Antonys International Review (Vol. 6, No. 2, February 2011); and Indias AfPak Strategy, RUSI Journal (Vol. 155, No. 1, March 2010).

I am extremely grateful to all those who supported me in the writing of this Whitehall Paper. Malcolm Chalmers was exceptionally generous with his time and expertise. He offered extensive guidance from start to finish, and carefully read several drafts of the manuscript. Andrea Berger and Hugh Chalmers were similarly helpful, and I could not have done without their frequent advice, particularly on a great number of technical issues. The paper benefited from the patient and expert editing of Adrian Johnson, with Ashlee Godwin. Saqeb Mueen and Daniel Sherman have been unfailingly supportive colleagues.

Many other individuals provided feedback, whether in writing or in conversation. Some of these would wish to remain anonymous, but I particularly want to thank Ali Ansari, Nick Beadle, Julian Borger, Jonathan Eyal, Peter Jenkins, Frank ODonnell, Andreas Persbo, Ian Stewart, Sir Harold Walker, and Heather Williams. I am grateful to others who commented on drafts at two workshops held at RUSI in June and August 2012. Finally, my greatest debt of gratitude is to Hannah Cheetham, Sundanda Joshi and Vinit Joshi.

Any remaining errors or shortcomings are, of course, mine alone.

- CBI Central Bank of Iran

- CIA Central Intelligence Agency

- GCC Gulf Cooperation Council

- HEU Highly enriched uranium

- IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency

- IDF Israeli Defense Forces

- ILSA Iran and Libya Sanctions Act

- IRGC Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps

- LEU Low-enriched uranium

- MEU Medium-enriched uranium

- NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- NIE National Intelligence Estimate

- NPT Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

- OPEC Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries

- RUSI Royal United Services Institute

- SIPRI Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

- SIS Secret Intelligence Service

- TRR Tehran Research Reactor

- UAE United Arab Emirates

- UK United Kingdom

- UN United Nations

- US United States

- USSR Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

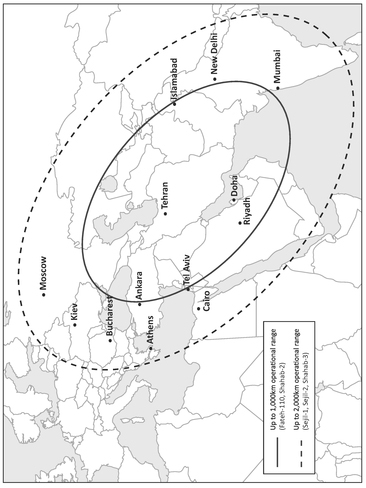

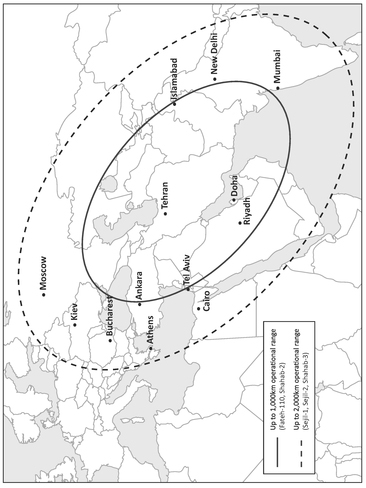

Map 1: Approximate ranges of Iranian ballistic-missile systems.

Six years ago, in mid-2006, Iran had no centrifuges spinning and possessed no enriched uranium. Robert Joseph, the US under secretary of state for arms control, declared that year: we cannot have a single centrifuge spinning in Iran. Iran is a direct threat to the national security of the United States and our allies.

Today, as President Barack Obama prepares to begin his second term, Iran has installed over 9,000 centrifuges, and has produced 6,876 kg of uranium enriched to 3.5 per cent, known as low-enriched uranium (LEU).

The quickening pace of Iran's nuclear activities, and its growing degree of 'nuclear latency' a state's temporal and technical proximity to acquiring a usable nuclear device has produced a sense of urgency amongst a number of countries, including Arab rivals of Iran. Iran's dogged pursuit of nuclear technology in the face of unprecedented pressure has also placed new stresses on the Iranian state itself. Indeed, a former senior Iranian diplomat, Seyed Hossein Mousavian, observes in his recently released memoirs that 'the nuclear Crisis has been the most important challenge facing the Islamic Republic's foreign policy apparatus since the 1980-88 war between Iran and Iraq'.

The first quarter of 2012 was especially fraught. Fears of an Israeli military attack on Iranian nuclear facilities peaked, European and American sanctions on Iran intensified, and Iran enriched uranium at its fastest-ever pace. A round of talks during 2012, beginning in April in Istanbul and concluding in June in Moscow, briefly eased this tension. However, these negotiations have failed, with Iran expecting but being refused sanctions relief, and the West remaining dissatisfied with Irans continued enrichment and lack of co-operation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The dialogue has now been downgraded to expert-level rather than political-level, reflecting the dim prospects of a settlement. Although the domestic political flux in the United States has now eased, making it easier for the second Obama administration to demonstrate flexibility in nuclear talks, Irans own politics are not going to stabilise until at least June 2013, when President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad will be replaced. This means that, despite the encouraging prospect of direct US-Iran talks beginning as early as November or December 2012, diplomacy might still struggle to find traction over the short-term, as sanctions begin to bite deeply.