2015 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045 ), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mart, Michelle, 1964

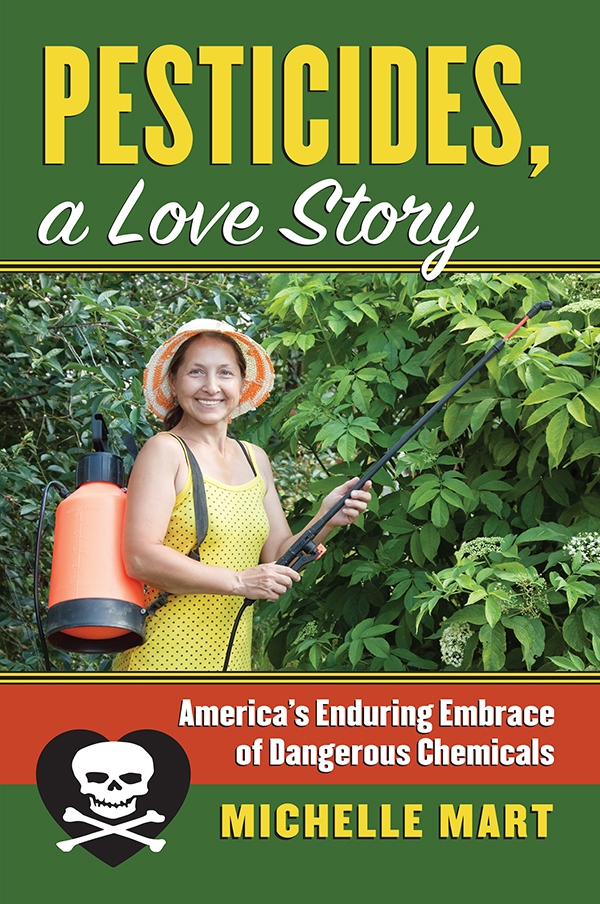

Pesticides, a love story : Americas enduring embrace of dangerous chemicals / Michelle Mart.

pages cm (CultureAmerica)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7006-2128-6 (hardback : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-7006-2157-6 (ebook)

.PesticidesUnited StatesHistory..Agricultural chemicalsUnited StatesHistory..PesticidesSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory..PesticidesUnited StatesPublic opinionHistory..Public opinionUnited StatesHistory..United StatesSocial conditions 1945 .NatureEffect of human beings onUnited StatesHistory.United StatesEnvironmental conditions.I.Title.

SB 950.2 .AM 37 2015

363.738'498 dc

2015020380

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10987654321

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z.- 1992 .

Introduction

Presto! No More Pests, read a 1955 article in Coronet magazine introducing the new pesticides aldrin and dieldrin to readers. These synthetics were not only easy to use, the article emphasized, they were sister miracle-workers for the housewife and back-yard farmer that did not harm other living things when used properly. This type of article was common in the mid- 1950 s, and similar messages were found in advertisements from chemical manufacturers. News stories and ads alike not only highlighted how easy it was to use pesticides or how powerful they were but also emphasized that American bounty was inextricably linked to the wonders of chemical agriculture. Readers, for instance, opened their Saturday Evening Post from 1952 to see a full-page Dow Chemical Company ad showing grocery-store customers buying large, lushly colored fruits and vegetables that were not the work of Mother Nature alone.

Who wouldnt love synthetic pesticides?

Apparently, most Americans did. At least there was evidence that they had been embracing these chemicals since news of them had first burst on the scene during World War II and continued to do so into the twenty-first century. More than percent of soybeans grown in the United States in 2008 , for example, were Roundup Ready genetically modified organisms (GMOs), dependent on the generous use of the herbicide glyphosate to control weeds.

This book is a story about this remarkable continuity, about how attitudes toward pesticide use remained relatively stable from the 1940 s to the present day. Why did synthetic pesticides become so pervasive, and, more importantly, why did they remain so? Why did popular and political attitudes toward pesticide use change so little over six decades, even in the face of numerous criticisms and crises that offered opportunities to rethink the commitment to synthetic pesticides?

Silent Spring, with the rise of environmentalism that was ushered in by its publication, was the most obvious turning point when faith in pesticides might have weakened. And it didbut only to a certain extent. The persistent insecticide DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and its chlorinated hydrocarbon cousins were banned a decade after Silent Spring was published, and the name DDT became synonymous with human abuse of the environment. But, contrary to the dominant story that we tell about the revolutionary impact of Rachel Carsons 1962 book, the overall commitment to pesticides did not lessen. Indeed, their use went up. Farm use in the United States more than doubled in the thirty years after Silent Spring was published. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, more than . billion pounds of pesticides were used annually throughout the world at a cost of $ billion, with the United States accounting for percent of the total amount used and percent of the money spent. What accounts for this paradox: the rejection of DDT and a strengthened commitment to pesticide use? One way to solve this puzzle is to uncover the origins of the story we tell about modern pesticides and their use.

Average Americans first learned of a new delousing powder, DDT, in early 1944 with news stories that the Allies had brought a raging typhus epidemic in Naples to a standstill. Within a few months, more stories reached the United States about DDTs successes against the malarial mosquitoalthough it was harmless to man, so far as the evidence goes, reported the New York Times. Hailed as the greatest single weapon in the war against [malaria] from 1944 on, DDT had a powerful effect on the American imagination. The story of modern American pesticides usually starts here, during World War II, with the embrace of DDT by most Americans as a chemical miracle bringing improved health and agricultural bounty. The real significance of this wartime moment thus lay in the transformation of American life that would follow.

DDT and its pesticide cousins were part of a technological revolution that reshaped American life, most visibly changing the operation of the nations farms. After the war, farmers used an array of mechanized equipment as well as mass-produced feed, seed, fertilizer, and synthetic pesticides. More broadly, the chemical revolution symbolized the confidence many Americans felt in their ability, through modern science, to tame and control nature, just as the United States was taming the rest of the world militarily, politically, and economically in the postwar era.

By the end of the twentieth century, the chemical age was no longer revolutionary; it was entrenched. Evidence that chemicals were woven into every aspect of modern life was well illustrated in the enduring power of pesticides. The types of pesticides used and the way that they were used had changed in half a century, but their ubiquity had noteven if they seemed less visible than in an earlier age. DDT was a powerful insecticide whose immediate effects were clear, as was its persistence. By the start of the twenty-first century, DDT was no longer sprayed across US fields; it had long been eclipsed by the herbicide glyphosate, better known to ordinary citizens by its brand name, Roundup. The shift from insecticides to herbicides had been going on for years and was accelerated by the introduction of genetically modified crops in the 1990 s. Although one of the arguments in favor of GMOs had been that they would reduce pesticide use by modifying crops internally instead of having to douse them with chemicals, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the GMOs that dwarfed all others in acres planted were Roundup Ready varieties of graincrops that could be safely sprayed with glyphosate and suffer no damage. The use of glyphosate doubled from 1996 to 2003 , with the majority of soybeans and corn planted in the United States being Roundup Ready by 2008 , and it had become the worlds largest-selling herbicide by 2004 , with $ million in sales annually. The whole point of chemical companies investing in herbicide-resistant GMOs was clear. Back in 1982 , an article in