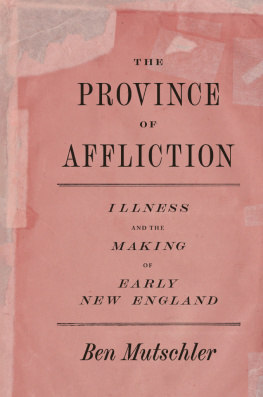

The Province of Affliction

American Beginnings, 15001900

A Series Edited by Edward Gray, Stephen Mihm, and Mark Peterson

Also in the series:

Trading Spaces: The Colonial Marketplace and the Foundations of American Capitalism

by Emma Hart

Urban Dreams, Rural Commonwealth: The Rise of Plantation Society in the Chesapeake

by Paul Musselwhite

Building a Revolutionary State: The Legal Transformation of New York, 17761783

by Howard Pashman

Sovereign of the Market: The Money Question in Early America

by Jeffrey Sklansky

National Duties: Custom Houses and the Making of the American State

by Gautham Rao

Liberty Power: Antislavery Third Parties and the Transformation of American Politics

by Corey M. Brooks

The Making of Tocquevilles America: Law and Association in the Early United States

by Kevin Butterfield

Planters, Merchants, and Slaves: Plantation Societies in British America, 16501820

by Trevor Burnard

Riotous Flesh: Women, Physiology, and the Solitary Vice in Nineteenth-Century America

by April R. Haynes

Holy Nation: The Transatlantic Quaker Ministry in an Age of Revolution

by Sarah Crabtree

A Hercules in the Cradle: War, Money, and the American State, 17831867

by Max M. Edling

Frontier Seaport: Detroits Transformation into an Atlantic Entrept

by Catherine Cangany

Beyond Redemption: Race, Violence, and the American South after the Civil War

by Carole Emberton

A complete list of series titles is available on the University of Chicago Press website.

The Province of Affliction

Illness and the Making of Early New England

Ben Mutschler

The University of Chicago Press

CHICAGO & LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-71442-4 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-71456-1 (e-book)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226714561.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mutschler, Ben, author.

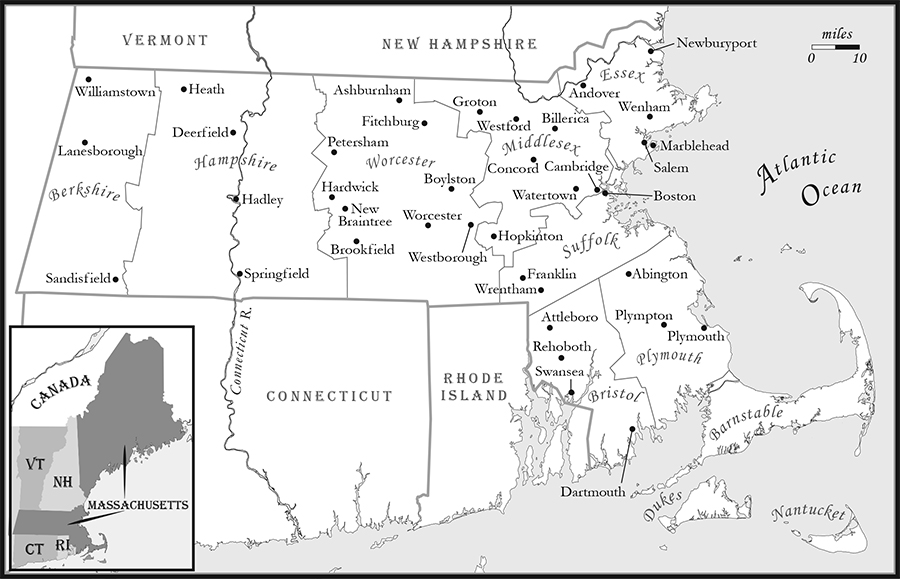

Title: The province of affliction : illness and the making of early New England / Ben Mutschler.

Other titles: American beginnings, 15001900.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Series: American beginnings, 15001900 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020000791 | ISBN 9780226714424 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226714561 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : DiseasesSocial aspectsNew EnglandHistory18th century. | DiseasesSocial aspectsNew EnglandHistory19th century. | Public healthNew EnglandHistory18th century. | Public healthNew EnglandHistory19th century. | New EnglandHistory18th century. | New EnglandHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC RA 446.5. N 48 M 87 2020 | DDC 362.10974dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020000791

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

TO THE MEMORY OF MY PARENTS, PHYLLIS HALEVY MUTSCHLER AND LOUIS HENRY MUTSCHLER

On a late summer day among one of Philadelphias leading families, when the thick heat in the city could rival places well to the south, young Henry Drinker happily chomped through a piece of watermelon until he ate too close to the Rine. It was an innocent enough mistake for a six-year-old to make. But as his mother surmised in her diary, that moment of youthful exuberance had been costly, the cause of Henrys vomiting and disordered bowels and the beginning of a serious sickness. Between late August and October 1777, Elizabeth Drinker kept a vigilant record of her sons precipitous decline and slow recovery. Henry voided 3 large Worms, and vomited one alive. He was unable to eat for nearly two weeks, reduced almost to a Skelaton, and ran a constant fever. While there were promising signs of recovery by September 6, when Henrys appetite began to return, his mother judged his illness to be an inviterate Bloody and white flux, a worrisome condition. She confessed, I cant help being happrehensive [sic] of his falling into a Consumption, which would be chronic and finally fatal. Henry had lived through earlier bouts of worms and bloody, mucous-laden stoolsand in his sufferings and recovery, he was typical of many children of his timebut his mother had seen enough illness in her family to fear the worst. At age forty-two, Elizabeth Drinker had already lost three children, two girls and a boy. The first little Henry, named after his father, had died as an infant in 1769.

Drinker viewed young Henrys progress in the coming weeks with a mixture of optimism and restraint. A promising morning was followed by a discouraging night; Henrys appetite continued to increase but his fever remained; and his bowels could come down in a frightfull manner, as they had on September 15, when they appeared red, Bloody and inflamd and cast a bitter smell through the room. There were continuous calls to the Pot, a steady administration of clysters (enemas) and other physic that Drinker appears to have applied both on her own and in consultation with physicians, and, above all, a good deal of careful watching and waiting. Finally able to have his britches put on and walk across the room with the help of a servant who had been charged with carrying him about the house, Henry suffered another setback at the end September, taken off his feet again by pains in his hams and a cold brought on by the autumn chill. It was not until October 26, two months after his initial sickness, that Elizabeth Drinker could signal Henrys full return to daily affairs. On that day, Drinker joined her sister, her three healthy children, and Henry at Quaker meeting, noting with relief the first time of our little Henrys going since his recovery.

The troubles had all started, in Elizabeth Drinkers mind, with a few errant bites of melon. As in so many other incidents in early modern life, the thin membrane separating the workaday world and a world of perils had been all too easily punctured.

***

The origins of this book lie in Henry Drinkers unfortunate encounter with that watermelon rind, in its evocation of the closeness of danger and the possibility of sudden change in everyday affairs. Elizabeth Drinkers remarkable diary, one of the richest accounts we have of daily life in eighteenth-century America, was my first window onto the ubiquity of sickness and other misfortunes in the period. But I subsequently found that while Drinkers diary is perhaps more insistent than other sources in its recording of illness, it is by no means exceptional.

Almost any source from the period reveals a world riddled by affliction. Letters contain polite inquiries into health and offer running accounts of the status of family, friends, and acquaintances. Newspapers and almanacs feature all manner of information about sickness: the spread of epidemics ravaging distant lands and neighboring colonies and towns, the arrival of infected goods and persons subject to quarantine and cleansing, and the sale of enslaved persons whose bodies are advertised as healthy and as already having weathered smallpox. Sermons seize on severe sickness as a warning that death might strike at any moment and as an inducement to examine the diseased state of ones soul. The acts and resolves of colonial assemblies depict a staggering range of afflictions besetting early modern folks. War veterans and their families ask for restitution for medical care; towns press for relief in the wake of epidemics; the injured, infirm, and simply unlucky plead for special licenses and exemptions from taxes, fees, or other public obligations. Government itself is subject to diagnosis and cure, the republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government in

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).