This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1942 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

A WEEK WITH GANDHI

By

Louis Fischer

ILLUSTRATED

Authors Note

This little volume is published through no fault of mine. I kept a careful diary during the week I spent with Gandhi. Lest those notes be lost or destroyed I wrote them out after I returned to America. A number of friends saw the manuscript and urged me to let it be published in full. I argued that it would be a very incomplete account of my visit to India. I had had many other talks in India which were important but off the record, I said. A book on Gandhi alone would not be a comprehensive book on India. Thats all right, my friends replied, say so in a foreword. I am saying so now.

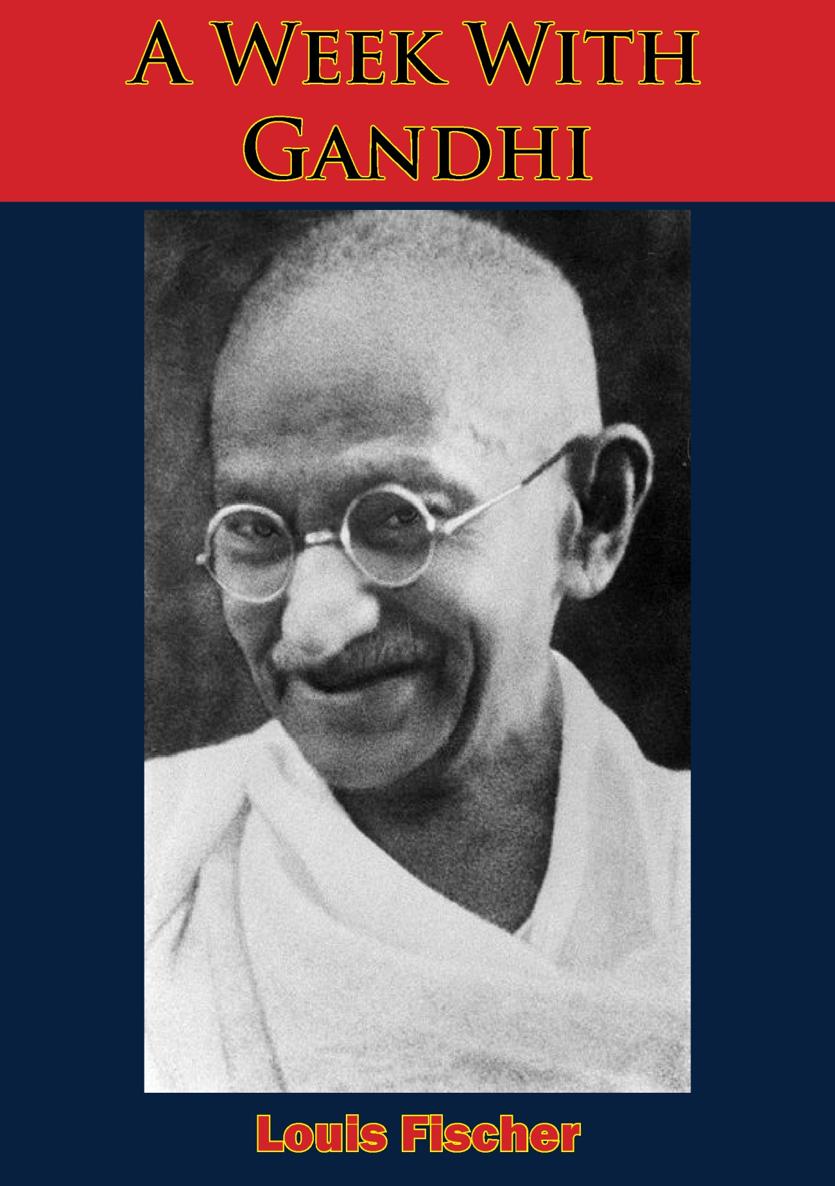

My talks with Gandhi were a rich, stimulating experience. Lord Linlithgow, the Viceroy at New Delhi, said to me, Gandhi is the biggest thing in India. That is correct. Gandhi is a unique phenomenon. Contact with his personality and mind is exciting. I made an almost stenographic record of everything he said to me. I reproduce it in the following pages. My own comments on Gandhi will be found in a short last chapter.

June 3, 1942

AFTER twenty-seven hours in the hot, dusty express train from New Delhi, I arrived in Wardha, a small town in Central India, at 8:30 p. m. Ten days earlier I had asked Jawaharlal Nehru to arrange an interview with Gandhi for me. In a few days Nehru wrote from Wardha saying that Gandhi would see me. He advised me to get into touch with Mahadev Desai, Gandhis secretary, to fix the time. I informed Desai that any time would do and he wired back: WelcomeMahadev Desai.

As I stepped out of the train at Wardha, a young man in white approached me and asked whether I was Fischer; when I said yes, he told me he had been delegated by Gandhi to meet me. A tonga was waiting. A tonga is a one-horse, two-wheeled carriage in which the passengers sit behind the driver with their backs to the horse. We drove through the darkness to the outskirts of town and got out at a house which an Indian millionaire nationalist had bequeathed to the Congress Party for use as a hostel. I slept on a big second-story porch open to the sky. All night an orange-white-green Congress flag fluttered with a kind of Morse-code noise.

June 4, 1942

I was up early and took a tonga with Gandhis dentist for Sevagram, the village which is Gandhis home when he is not in jail. The dentist said that England had been an understanding master. I tried to make him talk about Gandhi. He insisted on talking politics.

The tonga stopped. I jumped out and there stood a tall, brown-and-white figureGandhi. I walked towards him with long quick steps. He held his hand on the shoulders of two women who walked on either side of him. His thin brown legs were bare up to his loincloth. Leather sandals on his feet; a cape of cheesecloth around his shoulders; a folded white kerchief on his head. He said, Mr. Fischer, with an English accent, and we shook hands. He greeted the dentist, turned about, and I followed him to a flat, thick board resting on two metal trestles. He sat down, put his hand on the board, and said, Sit down. He said, Jawaharlal has told me about your book and the type of person you are, and we are glad to have you here. How long will you stay? I told him I could stay a few days.

Oh, he exclaimed, then we will be able to talk much.

A young man walked over to him, bowed low to his feet, and swayed up and down. Bas, has, Gandhi muttered. I imagined it meant Enough, and later found that my guess was right. Soon two other young men did the same thing, and again Gandhi shooed them off.

I asked him why he had chosen this village to live in. He said so-and-so, and he mentioned a name which I didnt get, had chosen it for him. I made no comment, but he noticed that I didnt catch the Indian name, and so he said Mira Ben was Miss Slade, an Englishwoman who had long been associated with him. He explained that it was her idea that he should live in a village in the center of India, and he had asked her to find the place. He did not wish to live inside the village because it was too unhygienic and noisy. It is better here, on the outskirts. The dentist started talking about false teeth, and Gandhi explained to him that the bite in the sets he wore was imperfect. A woman brought out a brass bowl filled with water and three sets of artificial teeth, and I decided to go. Gandhi said, You will walk with me in the evening and morning, and we will have other opportunities to talk. I bowed and went away.

I was given the freedom of Sevagrams guest housea one-room mud hut with earthen floor and bamboo roof. There are several beds in the room. Leading from the room is a tiny kitchen and also a water room with a stone floor on which stood a large number of tin and brass buckets and two tin washtubs, which Baithe aged maid kept filling with water carried in jars on her head from the village well. Gandhi had told me that I would be in the care of Kurshed Ben, or Sister Kurshed. Miss Kurshed Naoroji is a Parsi, aged about forty. She wore a coarse yellow homespun sari. She had studied singing in France and Italy for six years, but had dropped her musical career fifteen years ago and has since been a constant disciple of Gandhi. Her family are millionaires. Her grandfather, who died during the first World War at the age of ninety-five, was the first Indian member of the British House of Commons. Saklatvala, another Parsiand a Communist, was the third and last Indian member of the British Parliament.

Kurshed Ben is intelligent and quick. I argue with her that there has been an overemphasis here on Indian nationalism. An independent India, I contend, might become Fascist, and then it would have less freedom than under the British. She rejects this reasoning. She wants the British out first, and then the Indians will solve their own problems. We want to be alone, Kurshed said. It is like a housewife who has had guests staying with her for too long, and she is impatient to see them leave, and can think of nothing else but the pleasure of the moment when she sees them going out through the front door.

Kurshed took me visiting to several members of the Gandhi ashram, or community. They are all Congress field-workers or Gandhis secretaries, or just people who arrive and stay for a while to sit at the naked feet of the master. They come from various parts of India, and sometimes speak different Indian languages, so that they must communicate with one another in English. The children are very beautiful. I stopped in at Mahadev Desais hut. I found him, bald and paunchy, dressed only in a loincloth, sitting on a floor mat spinning on a primitive charka. His wife was in the next room, clothed in a much-twisted sari, doing likewise. Desai spins five hundred yards a day. The charka is a very simple machine which any peasant could make or buy cheaply. Desai said he travels a good deal and spins on trains. But he had never noticed anybody else doing it. Thanks to Gandhis propaganda and personal example, hundreds of thousands of Indian peasants had taken up home spinning in order to develop village industry and provide clothes for the almost-naked millions. But the habit has not spread very far, Desai admitted, and spinning is no factor in Indias national economy.