First published 2012 in India

by Routledge

912 Tolstoy House, 1517 Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place, New Delhi 110 001

Simultaneously published in the UK

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2012 Devi Prasad

Typeset by

Star Compugraphics Private Limited

5, CSC, Near City Apartments

Vasundhara Enclave

Delhi 110 096

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-415-51659-4

If a book can confirm that art is not a self-standing enterprise, but bears vital relations with public life and our material and spiritual path through the world, this fine collection of essays on Gandhi by one of Indias distinguished artists, will do so with a determination that comes from long experience of activism and of service to others.

Devi Prasads remarkable pottery is well known to many and since he has been the subject of a recent exhibition and a book by Naman Ahuja, so are his more diverse achievements in the arts, particularly in photography and painting. He is known too for his Gandhian activism. But what this book will bring to public knowledge is a lifetime of his reflection on Gandhian ideas.

The menu of Gandhian themes in this book is impressively wideranging and that should come as no surprise, given the close and extended relations that the author had with Gandhi in a very vital phase of his life in the forties through the Quit India movement, till Indian independence. Yet Devi Prasad does not restrict himself to Gandhi, the historical figure. Though he writes with personal insight about Gandhis historical importance, the essays also range over Gandhis thought and they uncover the mind and the philosophy behind the great campaigns of Indias anti-imperial struggle.

In a very brief Foreword, I can only mention one or two of the many instructive reflections in the pages that follow, so as to provide a stimulus to the reader for a more detailed and careful reading of them.

It is to be expected that a book on Gandhi by an artist and a craftsman and designer would be at its most assured and masterly in the discussion of Gandhis ideas on education. I say this is to be expected because Gandhi conceived of education as something that should be founded on making, not on learning, that it should involve the body and its habits as a path to the cultivation of virtue as well as to the development of skills and of understanding. This is a very different idea of moral education than the acquisition of principles and normative imperatives, and an artist is much more likely to elaborate it convincingly than an academic philosopher. Much is made by commentators on Gandhi of the affinities between him and Socrates. But I think there is nothing in the celebrated dialectical or dialogical method, quite like this link between the dispositions of the body and virtue, on which Gandhi rested his ideal of education. Nayee Talim, as it is expounded in this volume, is a quite radical departure from even the heterodoxies of a Socratic conception of education.

Having been an activist himself, initially with Gandhi, then with international peace movements, Devi Prasad, in successive chapters, writes at length and with the conviction of personal experience of his own youthful participation in the freedom movement, about Gandhis ideals of satyagraha and ahimsa, of civil disobedience and non-violence. My own view is that his discussion of education in other parts of the book should be read alongside these finely detailed discussions of participatory popular politics. The reason for this is central not only to a deep comprehension of Gandhi but for an understanding of the politics of our times. Gandhi understood well how much the standard forms of education provided by schools and colleges are essentially to build a class of career professionals, and broadly speaking, a ruling class. By contrast, real education by which the public comes to understand how society is structured and how it works, comes not in classrooms but on the sites of sustained popular movements. Thus, for Gandhi, just as we release our creative juices in the disciplines of the body and the skills it is capable of in an education based on making and crafting and coping with ones environment, we learn about the structures of the society we live in by our attendance and disciplined participation in the social and political movements of our times, whether it is the decades long freedom movement in India, or the revolutionary labour and peasant mobilisations that led to radical changes in different parts of the world, or in the civil rights or womens movement in America

On another matter too, Devi Prasads early experiences bestow on him a special authority. Anyone who has read it, knows that the correspondence between Gandhi and Tagore is much more than a personal and sympathetic exchange between two extraordinary men, who admired each other; it documents some of the most fiercely concentrated disagreements as well as convergences over some of the most vital philosophical issues in politics, political economy, culture, and human values. Devi Prasad, whose art and life were shaped by his close relations with both Tagore and Gandhi, is better situated than anyone else to explore those issues as they surface in these letters of unsurpassed substance. Though his book focuses on Gandhian themes, he speaks with an insiders knowledge about an entire field of interest that governs these two modern giants of Indian thought and sensibility.

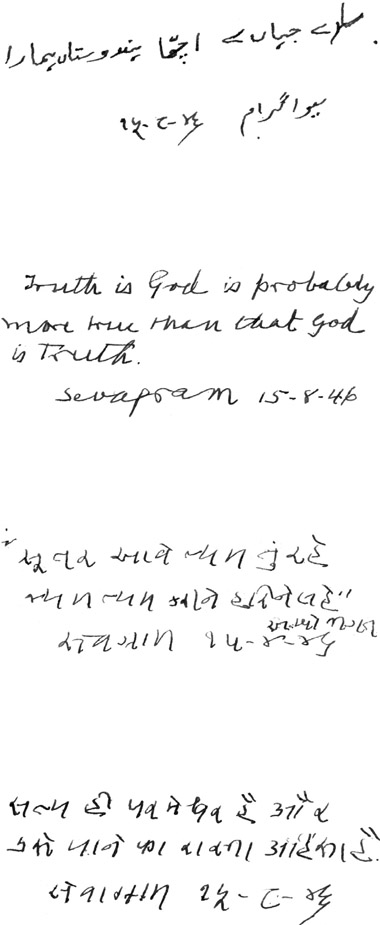

There is a prevalent, if glib, understanding of the debates undertaken in the correspondence, which contrasts the protagonists as the respective spokesmen of indigenist localism (Gandhi) versus universalist cosmopolitanism (Tagore). It is true that Gandhis ideal of a free and independent India envisioned a polity conceived in terms of highly scattered loci of power, and a political economy conceived as ensuring that the millions of peasants in a predominantly agrarian society were not left desolate by a lop-sided metropolitan conception of development. To put it negatively, it was based on a deep suspicion of the tendencies of modern capitalism and a centralised state that promotes its corporate tendencies. It found no alternative to such tendencies that did not stress the centrality of the villages of India and the peasantry, which inhabited them, and worked on the land. It is far from obvious that Tagore would lay the same emphasis on these things. But, however that may be, as Devi Prasad demonstrates, these arguments were made by Gandhi in the most cosmopolitan and universal spirit. He makes the point with a telling quotation:

My mission is not merely freedom of India, though today it undoubtedly engrosses practically the whole of my life and the whole of my time. But through the realization of the freedom of India, I hope to realize and carry on the mission of the brotherhood of man. My patriotism is not an exclusive thing. It is all-embracing and I should reject that patriotism which sought to mount upon the distress or exploitation of other nationalities. The con-ception of my patriotism is nothing, if it is not in every case, without exception, consistent with the broadest good of humanity at large.