MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2018

Text Shaun Crowe 2018

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2018

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Text design by Phil Campbell

Cover design by Phil Campbell

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

Printed in Australia by OPUS Group

9780522874051 (paperback)

9780522874068 (hardback)

9780522874075 (ebook)

Foreword

Shaun Crowes Whitlams Children is an excellent piece of research on a subject demanding academic analysis. It is well organised and written, using material from political science, international experience and interviews with major players. I particularly like the way he explored the issue as a scholar should rather than approaching the material within a straitjacket from which only one conclusion would be bound to emerge.

Using the Whitlam legacy as an overarching theme for the study was deliberately provocative and deliciously thought-provoking. The fact that both sides have a pointthe Greens with their reference to Goughs support for a new policy agenda, and Labor with its reference to his commitment to hard-headed electoral politicsillustrates the dilemmas involved in efforts at LaborGreen cooperation. It also raises the question of whether we might gain some insights by looking at the emergence of the Greens as the fourth split in Labor. After all, after the student rebellions of the 1960s, we did see a green Labor left emerge alongside and supported by the socialist left, a part of which was influenced by Marxism. Dissatisfied with the compromises associated with the search for majority support, some of these activists left to join the Greens.

The introductory chapters dealing with Australian history and political sciences understanding of the impact of social and cultural change on political parties are excellent, providing real context for the rest of the book. Looking to our history reminds us of the fluidity of things and of the existence of divisions within the parties, not just on strategy and tactics but also on philosophy and ideology. None of the two major parties are monolithic blocs, and nor are their leaders completely free to act. This makes efforts at cooperation (including coalition) problematic even when circumstances are leading them in that direction. True believers as we label themand on both sidesoften exercise more influence than their numbers might indicate.

Shaun Crowes discussion of parties and party systems reminds us that there are many ways to interpret political conflict and that the relationship between party and society is forever changing. What I very much like is the way this material was integrated into his analysis of the interviews he conducted. He shows how a commitment to post-materialism emerged from within democratic capitalism and played out, and how a belief in electoral and catch-all politics can represent a powerful ideological force. He shows too how what were originally mass parties can drift into cadre party status under the influence of professionalisation and the realities of elections.

I am not sure how it would have influenced his conclusions, if at all, but I felt he might have included a chapter on the preference question. The books focus is on relations between the Greens and Labor in parliament and government rather than in the electorates. Reference is made to the conflicts there, for example in inner-city Sydney and Melbourne, but there is no overall analysis of preference distribution and particular preference squabbles and what they might tell us about the relationship. Is it the case, as the Coalition often claims, that whatever looks to be the situation on the surface where we see differing degrees of hostility there is in fact a LaborGreen party just as in the past they claimed there was a LaborCommunist party?

In terms of identifying the major factors one needs to take into account to understand the relationship, Shaun takes us to pragmatism versus fundamentalism, jobs versus the environment, human rights versus public opinion, and fossil fuels versus sustainable growth. Others he might have reflected on include preference politics (as alluded to above), participatory versus representative democracy, and attitudes to trade unions and their rights at work. Again, I do not think a broadening of themes in this way would have changed the conclusions he reaches.

It is clear that any understanding of the future relationship will be, partly at least, based on ones assessment of the trajectory that will be taken by the Greens: further growth, a plateauing of influence or decline? Labor did emerge as a minority but became a majority party (i.e. able to win a majority of seats in parliament) on the basis that it represented a significant grouping (employees and their unions) and because it saw its primary political task as the winning of elections. It was able to speak for the nation and maintained that capacity despite the three splits and a more conflicted working-class electorate today. This does give it some degree of power status and appeal to potential members and MPs. Certainly, this was the view expressed by many Labor MPs in interviews for this book. Today we might ask whether the Greens constituency is large enough (and political enough) to go beyond its current minority status. Occasionally they express such expansive aspirations in terms of becoming Australias truly social democratic party. This would require the sort of compromise the ALP has been willing to make throughout its historyand it is hard to imagine a Greens equivalent.

What this all means is that Australia is stuck with two types of left party needing each other but not happy about that fact of political life. In particular, Labors traditional right faction and the Greens Marxist faction are obviously unhappy, being sworn enemies as they are. One might ask: is there a Whitlam-like leader of the ALP or of the Greens who would be willing to challenge these factions in the interests of a more permanent alliance?

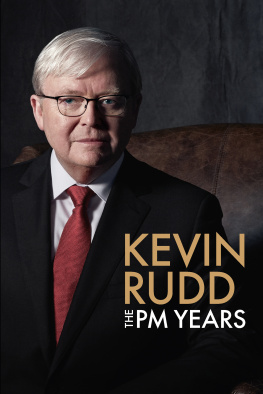

This leads me to make a point about the GillardBrown agreement. Whitlams Children shows that the Greens were happier about it than many on the Labor side. Was it the case that Gillards commitment to the agreement was the key (or at least a major element) in that defeat, or was it the case that Labors internal divisions (and flip-flopping on policy) were the key to its defeat? One can only speculate on how the Gillard government would have performed in the eyes of the electorate without the continuing conflict over her ascension to power at the expense of Kevin Rudd. The circumstances under which Gillard came to power and the continuous sniping related to it drained her leadership of the authority it needed to project the agreement with the Greens (and the independents) as indicative of her strengths and a positive force for good.