The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Anne G. Lipow Endowment Fund in Social Justice and Human Rights.

Permission to reprint has been sought from rights holders for images and text included in this volume, but in some cases it was impossible to clear formal permission because of coronavirus-related institution closures. The author and the publisher will be glad to do so if and when contacted by copyright holders of third-party material.

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2021 by Daniel Martinez HoSang

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: HoSang, Daniel, author.

Title: A wider type of freedom : how struggles for racial justice liberate everyone / Daniel Martinez HoSang.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021012050 (print) | LCCN 2021012051 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520321427 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520974197 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Race discriminationUnited StatesHistory. | Racial justiceUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC E 184. A 1 H 659 2021 (print) | LCC E 184. A 1 (ebook) | DDC 305.800973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012050

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012051

Manufactured in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Preface

RESTRUCTURING THE WHOLE OF AMERICAN SOCIETY

Freedom is a contested ideal. Many political visions in the United States and across the world have been pursued in its name. But what kind of freedom, and for whom? Partial, proprietary, and market-based models of freedom have shaped, and continue to shape, conditions of unfreedom and inequality in this country. Other possibilities exist. They have emerged within movements for racial justice and are predicated on a wider type of freedomone that would transform whole societies, not just particular circumstances, and end subordination, rather than simply shifting its terms.

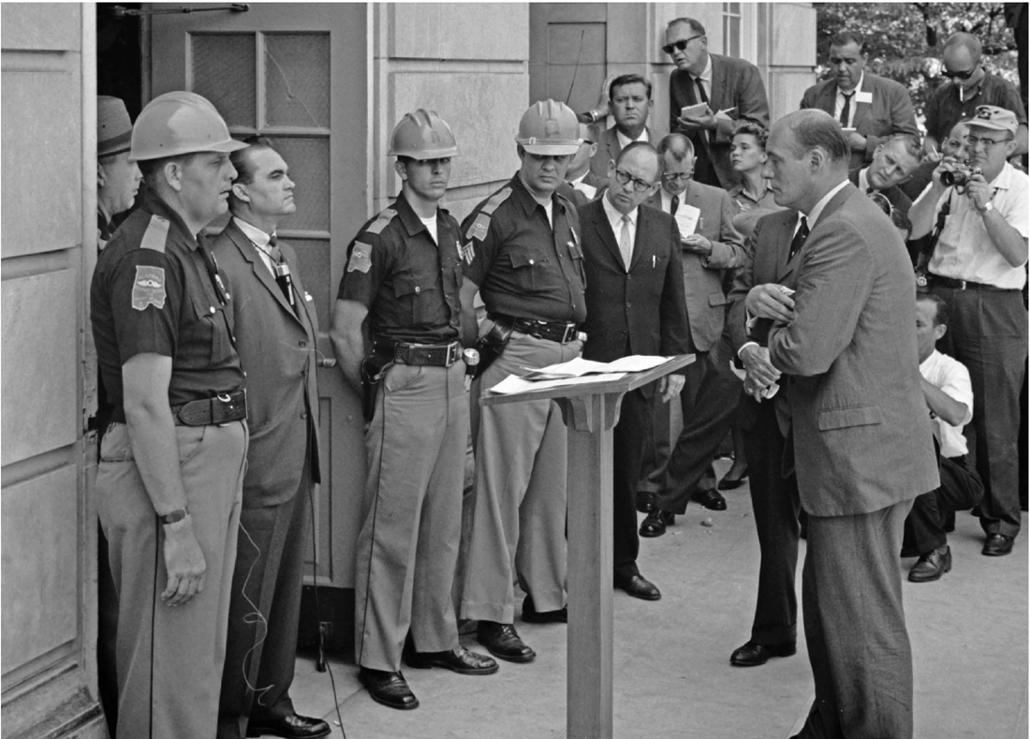

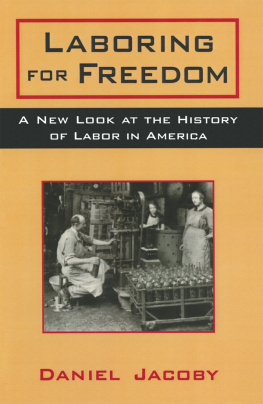

In one of the most iconic photos of the civil rights era, George Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama, stands on the steps of the University of Alabamas Foster Auditorium in Tuscaloosa. He is staring down US deputy attorney general Nicholas Katzenbach, while a gaggle of national reporters looks on. Outside the frame on that June morning in 1963 were Vivian Malone and James Hood, two Black students whose enrollment Wallace had sought to prevent, in defiance of a desegregation order from a federal judge. When after several hours Wallace abandoned his stand at the schoolhouse door, and Malone and Hood completed their enrollment, the episode was woven into a story about national progress against the moral wrongs of racism. That same evening, John F. Kennedy took to the airwaves promising new legislation to combat discrimination and end segregation in public education.

George Wallace stares down US deputy attorney general Nicholas Katzenbach at the University of Alabama, June 11, 1963. Credit: Warren K. Leffler/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection [LC-DIG-ppmsca-04294].

The story that Kennedy told pitted Wallaces racist image of freedom, in which the liberties of white people depend on the subordination of others, against a state-sanctioned anti-racism defined in terms of liberal values and full inclusion in the US market economy. Two points stand out. First, Malone and Hood are themselves erased from the picture, leaving two (white male) representatives of the state, Wallace and Katzenbach, center stage, and a third, Kennedy, as narrator. Second, the model of freedom that Kennedy celebrated was ambivalent at best. The abstract values of US liberalismfairness, opportunity, equalitycan expose people to, rather than shelter them from, violence, dispossession, and early death. And full incorporation into the market, as consumers, workers, citizens, and soldiers, can extract more than it provides.

The gains represented over the last half-century by a growing middle class of color, the opening of US immigration policy, resurgent demands for tribal recognition and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples, and claims for recognition by women and queer people of color are real and substantial. But liberal anti-racism based on individual rights and market opportunities alone also carries with it serious jeopardy. Once granted the freedom of opportunity, individuals become more, rather than less, responsible for their fate in the world. If that fate is hunger or unemployment, addiction or prison, we know who is at fault. This form of moral entrapment has a long history, unfolding through liberal policies that conferred freedom upon Black and other minoritized subjects who were looked on as inherently degraded. Communities and individuals freed by emancipation from bondage or the bestowal of citizenship, civil rights or other grants of opportunity, find themselves unable to refuse the culpability that shadows them.

Liberal rights and freedom, of the kind celebrated by Kennedy, can take as much as they give. They are fully compatible with industrialized forms of punishment and incarceration. They can serve to negate collective identities and historical perspectives, demanding that efforts to address disadvantage be channeled through individuals, not groups, and that past injustices play no part in present claims. In the context of the Cold War, they also played a crucial role in state-sponsored narratives justifying US militarism and global domination.

Malones and Hoods admission to the University of Alabama, and other stories like theirs, thus were simultaneously an affirmation of rights and a conscription into existing structures of power. As a form of redress they required the renunciation of many strategies that might actually dismantle prevailing structures of inequalitymaterial redistribution, historical reparation, or the recognition of collective demands. Dreams of emancipation can end with incorporation in the status quo.

But there have also been collectives who believed that the everyday functions of liberal democracyits models of governance, hierarchy, violence, and powerwere the source of their subordination, rather than their redemption. They have turned their intention instead to the abolition of militarism, state violence, and the appropriation of land and labor, to imagine the world anew.

At about the same time that Vivian Malone was finishing her first year of classes in Tuscaloosa, the organizer and social movement trainer Ella Baker gave a short talk to volunteers organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who had come to register voters in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Baker, who guided so many episodes of the Black Freedom movement, explained the stakes of their collective work: Even if segregation is gone, she told the group, we will still need to be free; we will still have to see that everyone has a job. Even if we can all vote, if people are still hungry, we will not be free ... Remember, we are not fighting for the freedom of the Negro alone, but for the freedom of the human spirit, a larger freedom that encompasses all mankind.