The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support

of the Anne G. Lipow Endowment Fund

for Social Justice and Human Rights

of the University of California Press Foundation,

which was established by Stephen M. Silberstein.

Racial Propositions

AMERICAN CROSSROADS

Edited by Earl Lewis, George Lipsitz, Peggy Pascoe, George Snchez, and Dana Takagi

Racial Propositions

Ballot Initiatives

and the Making of Postwar California

DANIEL MARTINEZ HOSANG

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu .

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2010 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

HoSang, Daniel.

Racial propositions : ballot initiatives and the making of postwar

California / Daniel Martinez HoSang.

p. cm. (American crossroads ; 30)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-26664-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-520-26666-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. CaliforniaRace relationsHistory20th century.

2. ReferendumCaliforniaHistory20th century.

3. CaliforniaPolitics and government1945I. Title.

F870.A1H67 2010 |

979.4'053dc22 | 2010008921 |

Manufactured in the United States of America

19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on Cascades Enviro 100, a 100% post consumer waste, recycled, de-inked fiber. FSC recycled certified and processed chlorine free. It is acid free, Ecologo certified, and manufactured by BioGas energy.

To Umai, Isaac, and Norma

Contents

Illustrations

FIGURES

TABLES

Introduction

Genteel Apartheid

One difference between the West and the South I came to realize... was this: in the South they remained convinced that they had bloodied their land with history. In California we did not believe history could bloody the land, or even touch it.

JOAN DIDION

In the 1990s, a series of controversial California ballot initiatives renewed a debate over the meaning and significance of race and racism in public life. Within a span of seven years, as the nation looked on, California voters passed propositions banning public education and public services for many immigrants (1994), repealing public affirmative action programs (1996), outlawing bilingual education (1998), and toughening criminal sentencing for adults and juveniles (1994, 2000).

At first blush, California seemed an unlikely site to stage such contentious struggles. During most of the 1990s, California Democrats, traditional supporters of civil rights since the New Deal, held a ten-point lead in voter registration rates, capturing all of the statewide offices by the end of the decade. Moreover, California voters appeared to take quite liberal positions on many other issues, approving ballot initiatives to increase the minimum wage and to legalize medical marijuana while rejecting measures backed by conservatives to establish a system of public school vouchers and to weaken the political power of unions.

Scholars and pundits have offered several explanations: demographic transformations fueled by a growing number of immigrants arriving from Asia and Latin America; upheavals in the states economy, including the steepest economic downturn since the Great Depression; and a series of opportunistic political actors who used the ballot process for their own partisan gain. All of these lines of inquiry are worthy of attention and, indeed, each tells part of the story. But in continuing to search for the exceptional forces that drove the racialized ballot initiatives of the 1990s, these explanations each rest on an important historicaland thus politicalassumption that deserves scrutiny. By tracing these conflicts to a unique set of contemporaneous economic, political, and social forces, we are left to understand them as a departure from broader historical patterns or continuities; as an effort to turn back the clock on the states history of racial progress. Indeed, in these narratives, white supremacythe ideological complex that explains hierarchy, destiny, and even fatality as an expression of innate human differenceis figured as an anachronistic and static force; progress itself is racisms greatest enemy.

Could it be possible instead that white supremacy as an ideological formation has been nourished, rather than attenuated, by notions of progress and political development? What if we imagine racism as a dynamic and evolving force, progressive rather than anachronistic, generative and fluid rather than conservative or static? What if we understand racial hierarchies to be sustained by a broad array of political actors, liberal as well as conservative, and even, at times, by those placed outside the fictive bounds of whiteness? And finally, what if the central narratives of postwar liberalismcelebrations of rights, freedom, opportunity, and equalityhave ultimately sustained, rather than displaced, patterns of racial domination?

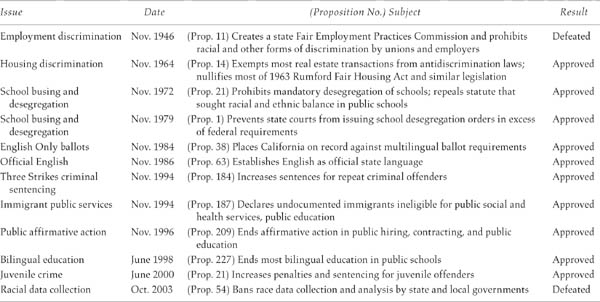

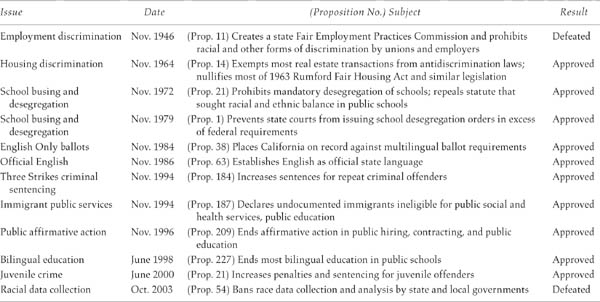

This book plows the soils of postwar California history in search of the conflicts, alignments, and political currents that preceded and produced the initiative politics of the 1990s, and it explores how the ballot propositions of that decade have shaped the states contemporary political culture. As suggests, across the postWorld War II era, Californias system of direct democracy has proven to be a reliable bulwark against many leading civil rights and antidiscrimination issues: California voters rejected fair employment protections in 1946, repealed antidiscrimination legislation in housing in 1964, overturned school desegregation mandates in 1972 and 1979, and adopted English Only policies in 1984 and 1986.

Taken together, this longer history of racialized ballot initiatives might suggest an opposite conclusion: that postwar California political history is characterized by an unchanging and undifferentiated racial domination, with rhetorical shifts simply masking an enduring racial animus. Yet this argument rests on equally ahistorical grounds, and reinforces the conception that progress and racism are natural adversaries: racism remains because we have made no progress.

Indeed, in the postwar era, rights and opportunity have been the lingua franca of California politicsthe state has imagined itself at the forefront of not only national but global progress and development, fettered only by the limits to its own imagination. During this period, we can also locate many of the forces and dynamics posited to be the engines of racial progress: a generally liberal political culture, a relatively robust economy, an increasingly diverse populace, and well-organized civil rights leadership. Yet as reveals, nearly every major civil rights and racial justice issue put before a vote of the people in California during this period has failed.

TABLE 1 Select Ballot Initiatives Examined, 19462003

Next page