Table of Contents

Guide

ALSO BY MANUEL PASTOR

Equity, Growth, and Community: What the Nation Can Learn from Americas Metro Areas

(with Chris Benner)

Just Growth: Prosperity and Inclusion in Americas Metropolitan Regions

(with Chris Benner)

Uncommon Common Ground: Race and Americas Future

(with Angela Glover Blackwell and Stewart Kwoh)

This Could Be the Start of Something Big: How Social Movements for Regional Equity Are Reshaping Metropolitan America

(with Chris Benner and Martha Matsuoka)

EDITED BY MANUEL PASTOR

Unsettled Americans: Metropolitan Context and Civic Leadership for Immigrant Integration

(with John Mollenkopf)

2018 by Manuel Pastor

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2018

Distributed by Two Rivers Distribution

Aint No Such Thing As Superman by Gil Scott Heron. Copyright 1978 by Cayman Music. Administered by Songs of Peer, Ltd. Used by Permission. All Rights Reserved.

My Back Pages by Bob Dylan. Copyright 1964 by Warner Bros. Inc.; renewed 1992 by Special Rider Music. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Reprinted by permission.

ISBN 978-1-62097-330-1 (e-book)

CIP data is available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Composition by dix!

This book was set in Garamond Premier Pro

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my parents, Manuel and Alba Gil Pastor

CONTENTS

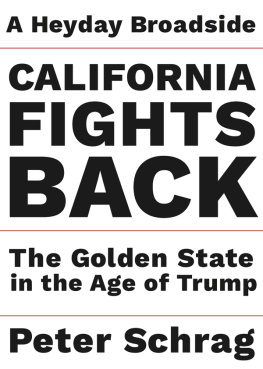

T he 2016 election of Donald Trump brought a sense of triumph to some but a sense of shock to others. Questions were quickly raised that looked both backward and forward: What went awry with the polling? Did last-minute interventions by the FBI make a difference? Who might be first of the many groups to be targeted by the new administration and just how bad might it get? With fears rising and declarations of #NotMyPresident beginning to roil social media, failed Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton stepped before a podium the next day and gracefully conceded. Expressing her faith in the electoral process, she offered hope that Trump would be a successful president for all Americans.

The reaction from California was markedly different. On the same day that Clinton accepted the results came a dramatic statement from the heads of the California State Senate and California State Assembly, Kevin de Len and Anthony Rendon, respectively. Expressing shock at the electoral turn of events and promising to challenge federal attempts to turn back progress on the environment, civil rights, and immigration, the two leaders concluded by writing that we will not be dragged back into the past. We will lead the resistance to any effort that would shred our social fabric or our Constitution. California was not a part of this nation when its history began, but we are clearly now the keeper of its future.

It was a rather remarkable declaration, not simply because a state so quickly and emphatically announced its rejection of the nations choice for president but also because it was California doing it. After all, this was the state that had foreshadowed the rhetoric Trump adopted with its own 1994 embrace of Proposition 187, a ballot measure designed to strip illegal immigrants and their families of access to nearly all social services, including education for undocumented children. Indeed, in some ways, the United States in 2016 was going through its own Prop 187 moment: a Republican politician, behind his Democratic competitor in the polls, successfully stirred up support for his candidacy by bashing immigrants, particularly Mexicans.

What changed? How did the Golden State complete an arc from anti-immigrant fervor to a seeming embrace of all Californians? How did it shift from the capital of car culture and suburban sprawl to a leadership position in combating climate change? What was the path from leading the nation in mass incarceration to becoming the first state to de-felonize all drug use? What led California, a place where income inequality worsened faster and earlier than in the rest of the nation, to become one of the first states in the nation to adopt a $15 an hour minimum wage? And what does all this mean for the rest of the country and for the American future?

California Matters

Understanding both what happened and what will happen in Californiaand rooting this story in larger structural forces and long histories of civic change, not just political personalitiesis certainly critical to the future of the Golden State. California may have moved from the crisis of division to a tentative state of repair, but tentative is the appropriate modifier: the state remains plagued by regional divisions, racial disparities, environmental challenges, and a desperate need to reboot the middle and shore up the bottom of the labor market. Addressing these issues will require creative policies as well as a new social compact that reflects the values, needs, and aspirations of all Californians. But while getting the state narrative right is an important part of that process, charting Californias past, present, and future is also important for the United States as a whole. Because as much as those in the Midwest, the South, New England, and indeed any other part of the country may hate to hear it, the demographic, economic, and social trends reveal a simple truth: California is America fast-forward.

A state once known for its own California Dream, complete with abundant sunshine, plentiful jobs, and sprawling single-family homes, California is also the state where America seemed to first unmoor and unravel. Part of this was a dramatic and sometimes disorienting demographic change: Californias ethnic makeup shifted dramatically between 1980 and 2000, with the non-Hispanic white share of the population falling from 67 percent to 47 percent. In the context of rapid Latino and Asian American/Pacific Islander growthalong with a profound process of deindustrialization that seemed to shake the foundations of the states working and middle classesan anti-immigrant fervor surged, finally culminating in the 1994 passage of Proposition 187.

Racialized conflicts were not limited to tensions about the newest Californians. With industrial employment shrinking, many turned to the relief that could be provided by drugs. Crack cocainea drug that soothed economic anxiety in that era in the same way that opiates do todayfueled the rise of militarized gangs that were, in turn, met by even more militarized police. In the late 1980s, Los Angeles police, years before the infamous 1992 beating of Black motorist Rodney King, were the proud owners of their own tank to batter down drug dens. Harassment was the order of the day; in one incident in 1988, nearly ninety officers broke open two apartment buildings, sprayed graffiti, detained nearly forty residents, and rendered nearly two dozen homeless without ever charging anyone with a crime.

Next page