Publication of this volume was aided by a gift from

Eric R. Papenfuse and Catherine A. Lawrence.

A volume in the Haney Foundation Series, established in 1961

with the generous support of Dr. John Louis Haney.

Copyright 2018 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used

for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this

book may be reproduced in any form by any means without

written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gigantino, James J., II, author.

Title: William Livingstons American Revolution / James J. Gigantino II.

Other titles: Haney Foundation series.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2018] | Series: Haney Foundation series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018007652 | ISBN 978-0-8122-5064-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Livingston, William, 17231790. | New JerseyHistoryRevolution, 17751783. | New JerseyPolitics and governmentTo 1775. | New JerseyPolitics and government17751865. | GovernorsNew JerseyBiography. | United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783.

Classification: LCC E302.6.L75 G54 2018 | DDC 974.9/03092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018007652

In the fall of 1778, William Livingston lamented to his cousin John Henry Livingston that he had not seen his family for more than two weeks in the previous two years. The hardships of prosecuting the American Revolutionthe lodging & diet and the numerous stratagems laid for himhad filled his days with indisposition, weariness, or discouragement. Dodging kidnapping plots and raids on his home, he believed that the Tories are ready to devour me, bones & all; yet he also felt that Providence supported him and made him useful to his country.

This book is about these types of hardships and discouragements that William Livingston, New Jerseys first governor, experienced during the American Revolution and, specifically, how he managed a state government on the wars front lines. Livingston, as a wartime bureaucrat, played a pivotal role in a pivotal place, prosecuting the war on a daily basis for eight years. Although few historians have paid serious attention to these state-level executive operations before, during, and after the Revolution, second-tier founding fathers like Livingston actually administered the war and guided the day-to-day operations of revolutionary-era governments, serving as the principal conduits between the local wartime situation and national demands placed on the states. William Livingstons American Revolution examines the complex nature of the conflict and the choice to wage it, the wartime bureaucrats charged with administering it, and the limits of that patriot governance under fire during and after the war.

This book, then, is as much about the position Livingston filled as about the man himself. The reluctant patriot and his position as governor quickly became one, as Livingstons distinctive personality molded his offices status and reach. A tactful politician, successful lawyer, writer, satirist, political operative, gardener, soldier, and statesman, Livingston became the longest- serving patriot governor during a brutal war that he had not originally wanted to fight or believed could be won. His prewar experiences put him in a difficult position as a wartime bureaucrat but also helped him seize power from an increasingly hostile legislature. The battle between Livingston and the legislature over control of governmental operations created a power relationship that allows an exploration of the dynamic prosecution of the war on a range of important issues, including the role of finances, the battle against loyalism, and the creation of a new federal government that benefited from the lessons of the Revolution. In each area, Livingston contended for increased executive power, effectively arguing that the governors office served as the primary guardian of state power, as opposed to the elected legislature or the militia, both of which he often criticized for bowing to the will of a fickle electorate. His vantage point on the war was much wider than most. He not only sat for the wars entirety in a central political position but also served in both the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, holding high political office continuously from 1774 to 1790. As a founding father, Livingston not only saw it all but also contributed substantially to the new nations making at every level.

Despite his efforts to improve the condition of New Jersey during the Revolution, Livingston remains one of the forgotten founders. No complete biography of him has appeared since 1833.

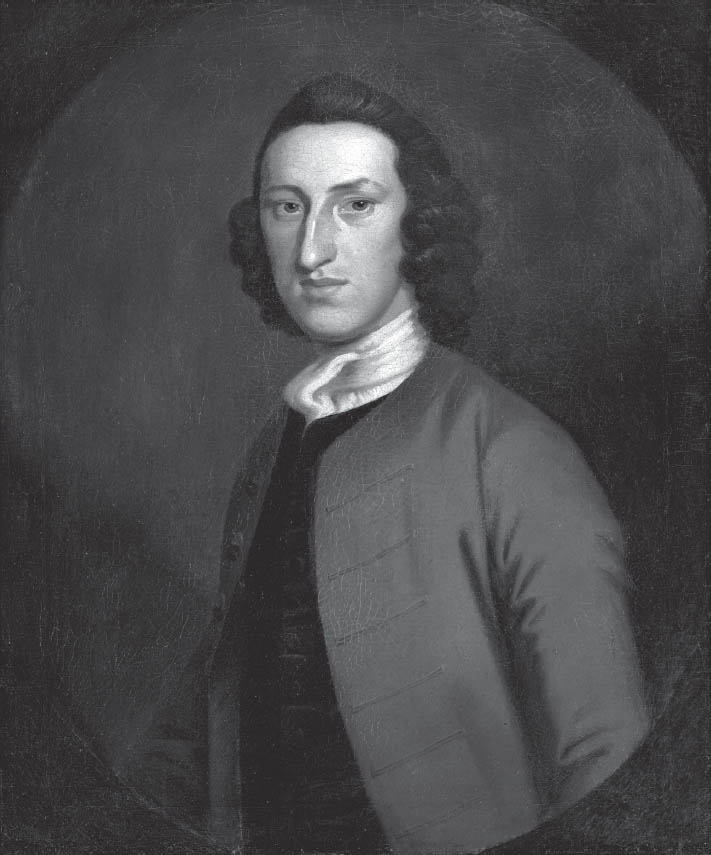

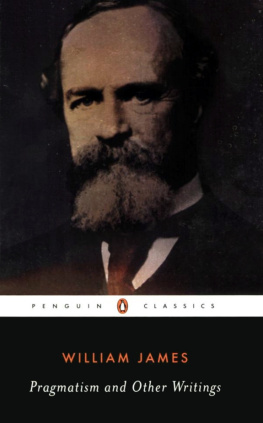

Figure 1. William Livingston. Portrait by John Wollaston (c. 1750). Courtesy of Fraunces Tavern Museum, New York City.

An examination of this distinctive individual in a locale central to the revolutionary movement sheds new light on the Revolutions impact on politics, the economy, and common people while engaging several important historical questions. The first theme explored here is the choice to go to war. Livingstons struggles with independence as he served as a delegate to the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1776 reflect the same difficult choices faced by thousands of Americans. Moreover, Livingston epitomizes those founders who saw the revolutionary movement in royalist terms. Several founders believed that Parliament had usurped the prerogatives of the crown after the Glorious Revolution and inappropriately interfered with issues, including colonial affairs that should have been the sole province of the king. Livingston and others hoped George III would exert a stronger executive authority against Parliament, though popular Whig ideology that converted many to republicanism soon overtook this line of reasoning as the war began. This popular ideologysomething Livingston never took comfort inremade New Jerseys patriot government and led to Livingstons ejection from the Continental Congress in June 1776 for his continued opposition to immediate independence. Livingston never abandoned his royalist leanings and retained both a strong interest in greater executive authority and a healthy suspicion of legislators, beliefs that dramatically affected how he prosecuted the war in New Jersey.

Livingstons moderation provides a model with which to explore the