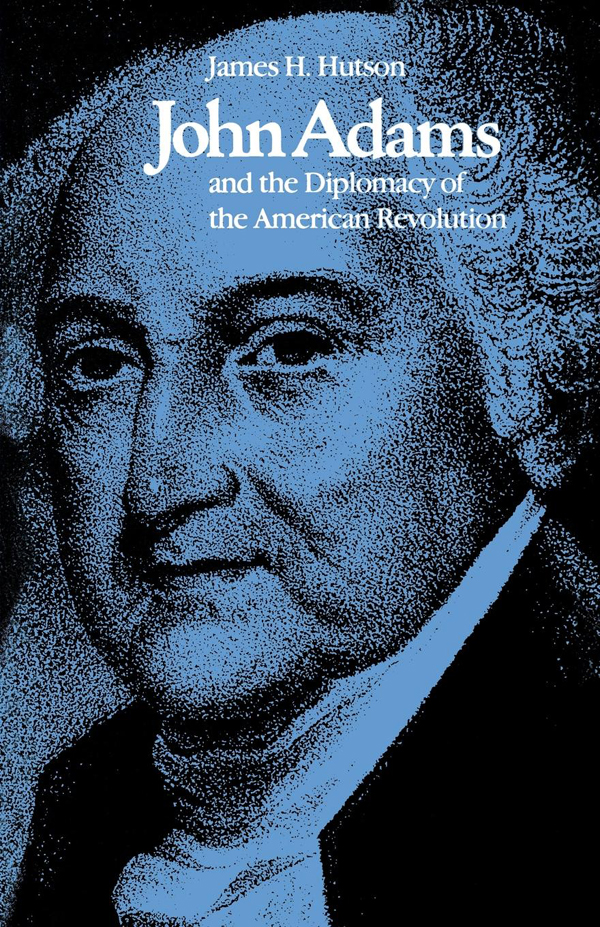

James H. Hutson - John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution

Here you can read online James H. Hutson - John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: University Press of Kentucky, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution

- Author:

- Publisher:University Press of Kentucky

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

JOHN ADAMS

AND THE DIPLOMACY

OF THE AMERICAN

REVOLUTION

JAMES H. HUTSON

JOHN ADAMS

AND THE DIPLOMACY

OF THE AMERICAN

REVOLUTION

FOR KATHY

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Hutson, James H

John Adams and the diplomacy of the American Revolution

Bibliography: p.

Includes Index.

1. United StatesForeign relationsRevolution, 17751783 2. Adams, John, Pres. U. S., 17351826. I. Title.

E249.H87973.3209247957575

ISBN 9780-81315314-8

Copyright 1980 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth

serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky,

Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club,

Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society,

Kentucky State University, Morehead State University,

Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,

Transylvania University, University of Kentucky,

University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506

Edmund S. Morgan, Sterling Professor of History, Yale University, has read and criticized this manuscript twice and has encouraged me to publish it. Without his assistance and moral support at critical periods, it would have never become a book. Stephen G. Kurtz, now principal of Phillips Exeter Academy, also helped me by interrupting his busy schedule and giving the manuscript a tough-minded reading. Several other people have assisted me in ways of which they, perhaps, were not aware: Mr. and Mrs. David Hutson, Mrs. Joseph Hranac, Gayle and Tracey Weber, and Benjamin and Scott Hutson. I am grateful for the opportunity of working at an institution as hospitable to ideas as the Library of Congress and would like, in particular, to acknowledge the intellectual stimulation supplied by my colleagues in the Manuscript Division.

The foreign policy of the American Revolution was not revolutionary. The ideas shaping it were those that informed European diplomatic thinking throughout the eighteenth century. Colonial Americans adopted those ideas as readily as they did the fashions, the books, and the other appurtenances of European culture that they imported so avidly. John Adams and his fellow statesmen of the Revolution absorbed the ideas as they grew up and, in 1776, applied them to the new American nations relations with foreign powers.

Eighteenth-century European diplomacy, writes Felix Gilbert, was entirely dominated by the concept of power. Its key ideas were the balance of power, which apologists promoted as an enlightened mechanism to secure peace, and the doctrine of the interest of states, according to which interest was the sole arbiter of political action.

A diplomacy based on power was congenial to eighteenth-century Americans because they subscribed to a theory of politics, propounded by English Opposition writers, which stressed that the ultimate explanation of every political controversy was the disposition of power. The sensitivity of colonial Americans to power was, according to a leading expositor of their ideas, one of the most striking things in their thinking. Even had colonial Americans never heard of the English Opposition, they would have been attentive to power in politics because of their long conflict with the French. The object of the wars with France was dominionpower over the North American continent. Therefore, an appreciation of power in politics was natural for the colonists.

In soliciting British assistance against the French, the colonists invoked religion and morality far less than self-interest and power, for they correctly assumed that British statesmen were more likely to be moved by calculations of power than by reminders of religious affinity. At every crisis with the French, Americans stressed to the British that they could not afford to lose the colonies because they were the source of their national power and of their weight in the European balance. James Logans Of the State of the British Plantations in America demonstrates that Americans had perfected this kind of appeal by 1732. Logans paper was laced with references to the true Interest, the present Interest, of Britain and her European competitors. And it insisted that Britains power and her position in the European balance was derived from America. The principal Security of Britain, wrote Logan, consists in its Naval force and this is supported by its Trade and Navigation. [It is no] less certain that these are very much advanced by means of the British Dominions in America; the Preservation of which is therefore of the utmost importance to the Kingdom itself, for it is manifest that if France could possess itself of those Dominions and thereby become Masters of all their Trade... they would soon be an Overmatch in Naval Strength to the rest of Europe, and then be in a Condition to prescribe Laws to the whole. The American Plantations, Logan concluded, are of such Importance to Britain, that the Loss of them to any other Power, especially to France might be its own ruin.

King Georges War (the War of the Austrian Succession) produced the customary American appeals to Britain: All parts of the Empire were interdependent, wrote Massachusettensis in 1746, and if the Colonies were lost... Britain would lose its own independence too.

Most of the leaders of the American Revolution matured during the French and Indian WarJohn Adams graduated from college the month of Braddocks defeatand they adopted as their own the attitude toward foreign affairs which prevailed during that period. Since few statements by leaders of the Revolution survive from the 1750s, the proof of this contention must principally rest on the similarity between the foreign-policy assumptions of the Revolution and of the French and Indian War. John Adams is unusual in that he left statements about his youthful attitude toward foreign affairs which show the continuity of his views between the 1750s and the 1770s.

From a tender age Adams was thrilled by the prospects of American power. At ten he thought the men of Massachusetts a race of heroes, who would have cut to pieces at once the Duke DEnvilles army had it dared attack Boston. In 1755 so great was his confidence in the resolution of my countrymen, that I had no doubt we could defend ourselves against the French, and that better without England than with her. Adamss youthful cockiness fed upon a vision of American greatness which was widely held in the colonies and which was nothing less than a beliefdecades before scholars usually locate itin the countrys manifest destiny. New Englanders believedwith rapture, Adams recalled later in lifethat the Pilgrim Fathers had chiseled into Plymouth Rock the prophecy:

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution»

Look at similar books to John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.