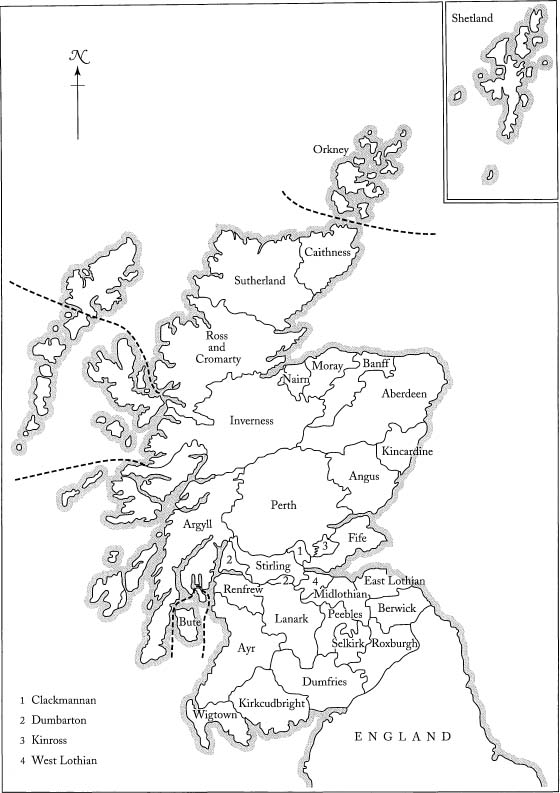

SCOTLAND IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

SCOTLAND IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

UNION AND ENLIGHTENMENT

David Allan

First published 2002 by Pearson Education Limited

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2002, Taylor & Francis.

The right of David Allan to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN 13: 978-0-582-38247-3 (pbk)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library

Typeset in 11/13pt Baskerville MT hy Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong

CONTENTS

In producing a work such as this, one inevitably accumulates debts to other people, and it is a pleasure to acknowledge their assistance here. Numerous friends and colleagues shouldered the burden of reading and commenting on my drafts, frequently (though probably not always) saving me from myself: Rab Houston, Keith Brown, Bill Knox, Bruce Lenman, Richard Saville, Robert Crawford, Nicholas Phillipson, Alexander Murdoch, Andrew Mackillop, Roger Emerson, Andrew Nicholls, Mark Spencer, Helena Thorley, Alexander Thorley, David Palmer and Katie Price (now Allan). I am grateful also to Hamish Scott for some important kindnesses, and to Andrew Maclennan and Heather McCallum at Longman for editorial support throughout the period from proposal to publication. Finally I should mention those undergraduates in the University of St Andrews to whom I have tried to explain different aspects of eighteenth-century Scotland. They may be surprised to learn that their suggestions and encouragement were important factors in the completion of this book.

Nation

One issue above all was made so problematical by eighteenth-century events that it continues to perplex the Scots even today: their nationhood the need continually to ask Who are we? The answer, of course, has never been entirely straightforward. A convoluted political and religious relationship with the English, the unavoidable fact of extreme geographical proximity and deeply rooted ethnic and linguistic ties have ever muddied the water. Yet the late-medieval conflicts with England, continuing sporadically into the sixteenth century, had somehow fashioned a collective identity among Scotlands disparate inhabitants, infusing them with a profound sense of their own separateness. If knowing what properly defined a Scot remained complicated first amid intensifying hostilities between the countrys Gaelic-speaking Highlanders and Scots-speaking Lowlanders and then because of the peoples own violent religious differences following the Reformation a working solution to the problem, frequently repeated and almost universally endorsed by all ranks and persuasions, gradually emerged. Whatever else they might be, the Scots, by the later seventeenth century, could at least be sure that they were not English.

The impact of the Treaty of Union, by whose ratification in 1707 the last Edinburgh Parliament agreed that Scotland should be incorporated into a newly forged British state governed from the English capital, was therefore necessarily unsettling. Deciding whether to establish these new arrangements in the first place, as well as which of several possible variant forms they might take, inevitably caused internal convulsions. All manner of other issues were also left unresolved for the Scots by the creation of a new polity. Key questions were in fact settled not in the surprisingly laconic treaty but in the slow and difficult evolution of political practice over succeeding decades: What precisely was to be the new role of Scotlands politicians and institutions? How might the Scots secure their own interests within a predominantly English state? And would Westminster seek to preserve or to erode Scotlands distinctiveness? Even less clear were the ramifications for the Scots identity. In particular, if nationhood were ordinarily expressed through the free exercise of sovereign self-government, had Scotland itself also ceased to exist in 1707? Whatever their views, and however they preferred to answer these questions, all Scots were forced to confront the consequences of Union. It is with the background to this epochal event that we must begin.

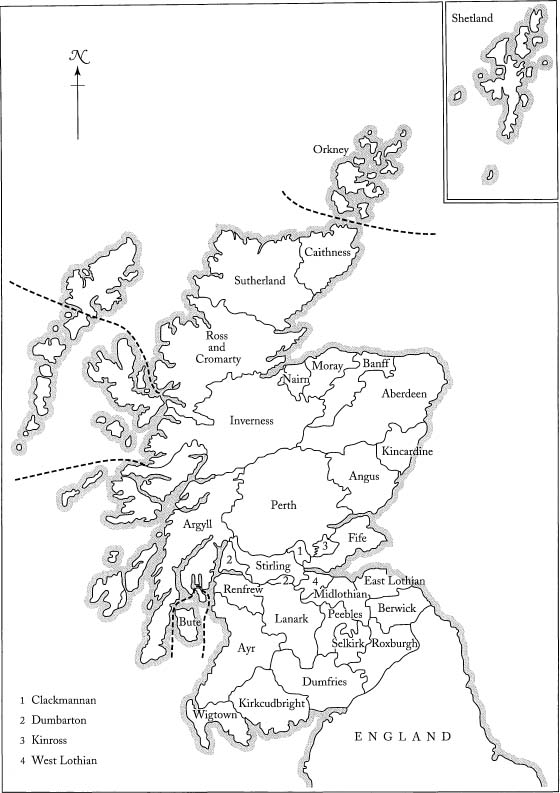

Eighteenth-century Scotland

In 1700 the separate kingdoms of Scotland and England still had a considerable distance to travel before their slightly awkward marriage could be consummated. Mutual suspicion, at times verging on a complete breakdown in relations, marked the notably cantankerous years leading up to the treaty. Superficially it can appear that Union was the result of irresistible processes of convergence that, if not quite inevitable, it was the product of long-term forces pressing the two neighbours ever closer to some kind of lasting political unification. While this interpretation certainly dominated between the eighteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, recent historiography, less deferential towards older pieties, has begged to differ. It is now generally agreed that, although specific trends of convergence can indeed be identified as far back as the sixteenth century (especially those arising out of both peoples shared formal commitment to Protestantism), so too were deeply rooted patterns of divergence also strongly evident. These were in fact still driving the two old enemies further apart until a surprisingly advanced stage in the pre-Union proceedings.

The political developments of the seventeenth century were not the least of the hindrances to closer and happier Anglo-Scottish relations. The experience of the regal union or union of the crowns, stemming from 1603 when James VI of Scotland had succeeded his mothers childless cousin Elizabeth, Queen of England, thus beginning an often unhappy arrangement by which two historically antagonistic kingdoms shared the same monarch, lay at the root of the strained relationship. Pro-unionists ever since 1603 have pointedly interpreted this royal connection as a milestone on the road to greater intimacy; and the Treaty of Union was indeed, as we shall see, in many ways a solution to the constitutional and diplomatic tensions which were James VI and Is peculiar legacy to his successors (though it was not, it should be added, the only possible solution: elsewhere in seventeenth-century Europe, the Habsburgs awkward tenure of both the Bohemian monarchy and the German emperorship did not result in a unified state). But the intrinsic problems of multiple monarchy, especially when it is remembered that a third throne that of Ireland came along with Jamess English inheritance, led many Scots to even greater resentment of Englands pre-eminence within the British Isles. It also prepared them to resist any suggestion that their own future might lie with absorption in what would inevitably be an anglocentric polity.