www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Original text copyright 1965 by Hodding Carter

Reprinted by the University Press of Mississippi, 2016, by permission of Hodding Carter III

Introduction copyright 2016 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Carter, Hodding, 19071972, author.

Title: So the Heffners left McComb / Hodding Carter II.

Description: Jackson, MS : University Press of Mississippi, [2015] | Series:

Civil rights in Mississippi | Originally published: 1965.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015041907 (print) | LCCN 2015042201 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496807489 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781496807472 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781496807496 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Heffner family. | Race discriminationMississippiMcComb. | Heffner, Albert W., Jr. | Heffner, Mary Alva. | ViolenceMississippiMcComb. | HarassmentMississippiMcComb. | Civil rights movementsMississippiMcComb. | African AmericansCivil rightsMississippiMcComb. | McComb (Miss.)Race relations. | McComb (Miss.)Biography.

Classification: LCC F349.M16 C3 2015 (print) | LCC F349.M16 (ebook) | DDC 323.1196/073076223dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015041907

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

reinforced by a neighbors grant

FIGURE FOUNDATION

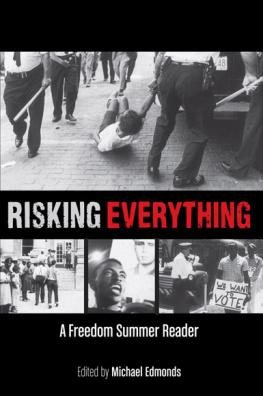

INTRODUCTION

Trent Brown, 2016

It is clearly not easy for man to give up the satisfaction of this inclination to aggression. They do not feel comfortable without it. The advantage which a comparatively small cultural group offers of allowing this instinct an outlet in the form of hostility against intruders is not to be despised. It is always possible to bind together a considerable number of people in love, so long as there are other people left over to receive the manifestations of their aggressiveness.

FREUDCivilization and Its Discontents

On Saturday, September 5, 1964, the Labor Day weekend, the family of Albert W. Red Heffner Jr. left their house at 202 Shannon Drive in McComb, Mississippi, where they had lived for ten years. They never returned to the town. On July 17 of that summer, they made a decision that would within a few weeks cost them their home, Reds job, the friends they thought they had made in the small southwest Mississippi city, and their peace of mind. Weve had it, Reds wife Mary Alva (Malva) told a reporter after they How is the civil rights work going? a womans voice asked. After realizing the potentially dangerous nature of the call, Sweeney hung up the telephone. Later that evening, cars began circling the Heffners block.

Over the next weeks, the anonymous phone calls continued, becoming increasingly vulgar and threatening. Malva recalled that they eventually received more than three hundred harassing calls. People in the neighborhood, if not active participants in the intimidation campaign against them, were certainly aware of the dangers the Heffners faced. One afternoon a four-year-old boy asked Mrs. Heffner, When is your house going to be bombed? a reasonable question considering the level of violence in the town that summer. Red Heffner had seen his role only as a possible line of communication between respectable white McComb and the civil rights workers. Even though he informed police chief George Guy, a man he considered to be his friend, of his actions and attempted to explain his reasoning to people in

The fall of the Heffners from the communitys grace was swift and complete. Their story demonstrates the power of fear, conformity, community pressure, and threats of retaliation of many sorts that silenced so many white Mississippians against the violence of the summer of 1964 as well as during the longer period of the civil rights movement in the state during the 1950s and 1960s. So the Heffners Left McComb is journalist Hodding Carter IIs succinct account of the events that led to the Heffners downfall and flight from their home. It is not a history of the broader civil rights movement in the city or of the voter registration campaign that triggered a wave of violence in McComb that summer. It concentrates instead on the background of the Heffners, their immediate actions in the early summer of 1964, and the campaign of intimidation that drove them from their hometown. Even on those terms, it is not an account of the full communitys thoughts and actions. Black McComb figures very little in Carters account, as he admits. The best role he could imagine for them in a telling of the communitys story is as a shadowy, contrapuntal chorus (10), a metaphor that says much about the limits in those days even of a sympathetic white Mississippian such as Carter. The students and other volunteers who came for the Mississippi Freedom Summer, Carter sets down as engaged in an idealist if foolhardy project (10). Their plans, voices, and fates receive little attention here. No, the book is by design an account of white McComb and its rejection of the Heffners. It is easy to see what Carter omitted, some things by design and others because he wrote the account immediately after the events he recounts. But by showing how acutely community pressure could turn on and drive away one previously respected white family during the most intense period of the civil rights movement in Mississippi, Carters book stands as an important but largely neglected document.

Early histories of the civil rights movement, as well as many popular accounts, focus on leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., opponents such as George Wallace, or action or inaction at the national level by Congress or Presidents Kennedy or Johnson. More recent scholarly work generally concentrates on local people, either activists or opponents of reform. Carters book, on the other hand, features a family that never chose to make a stand on the principles of the struggle in that time and place, yet were deliberately and systematically punished and driven into exile for what white McComb perceived as a most serious breach of the racial solidarity upon which the community rested and depended. Like most of their white middle-class peers in McComb, the Heffners felt invested in their community, church, and other local institutions. That investment led them to seek a way of understanding what was happening locally as national attention and grassroots pressure intensified on what most whites called without sarcasm the Mississippi Way of Life. The Heffners felt that the voter registration campaign in the state that summer and the violent white response to it represented something new and potentially disruptive to their community, and hoped through mediation or at least communication to end the violence that had begun in McComb as soon as the first outsiders had come to town. The longer tradition of violence against local blacks, on the other hand, seemed never to have excited much attention from Red Heffner. That violence was certainly less visible or somehow simply less troubling even to moderate white McComb, if only because it did not figure so prominently in the local or national press or in conversations with other community leaders and respectable people. Nor, it should be noted, did that longer pattern of violence against black McComb feature a summer dynamiting terrorist campaign, as happened in 1964.