Ohio University Research in International Studies

This series of publications on Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Global and Comparative Studies is designed to present significant research, translation, and opinion to area specialists and to a wide community of persons interested in world affairs. The series is distributed worldwide. For more information, consult the Ohio University Press website, ohioswallow.com.

Books in the Ohio University Research in International Studies series are published by Ohio University Press in association with the Center for International Studies. The views expressed in individual volumes are those of the authors and should not be considered to represent the policies or beliefs of the Center for International Studies, Ohio University Press, or Ohio University.

Executive editor:

Gillian Berchowitz

Southeast Asia Series consultants:

Elizabeth F. Collins and William H. Frederick

2017 by the Center for International Studies

Ohio University

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

Printed in the United States of America

The books in the Ohio University Research in International Studies Series are printed on acid-free paper

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Espiritu, Talitha, author.

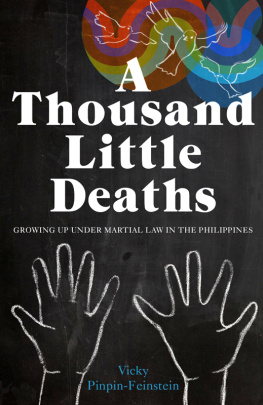

Title: Passionate revolutions : the media and the rise and fall of the Marcos regime / Talitha Espiritu.

Description: Athens : Ohio University Press, [2017] | Series: Ohio University research in international studies. Southeast Asia series ; no. 132 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017000722| ISBN 9780896803121 (pb : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780896803114 (hc : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780896804982 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: PhilippinesPolitics and government19731986. | PhilippinesHistoryRevolution, 1986. | Mass mediaPolitical aspectsPhilippines. | Politics and culturePhilippines. | Mass media and culturePhilippines.

Classification: LCC DS686.5 .E87 2017 | DDC 959.904/6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017000722

Introduction

THE POWER OF POLITICAL EMOTIONS

The dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos came to an ignominious end on February 25, 1986. After twenty-one years in power, Marcos fled the Philippines following a four-day popular revolt dubbed people power. The euphoria in the streets was televised live around the globe. With the force of national allegory, these televised images conveyed a seemingly incontrovertible message: here is visible evidence that a peoples democratic aspirations can triumph over authoritarianism; here is proof of the utopian possibilities of political emotions.

The political spectacle of people power conjoins two stories, each one pivoting on the activation of emotion in the political sphere. On the one hand, there is the melodramatic story of how Marcos rose to power by creating a national family, a political fantasy that was both seductive and treacherous in its claims to transform the nation into a postcolonial utopia via a dictatorship of love. On the other hand, there is the story of how a sentimental culture of protest grew in close proximity to the official political sphere, an intimate public laboriously channeling the moral outrage of a people pained by the egregious excesses of the Marcos regime. The media figured prominently in both these stories. Marcos, after all, was a master of the political spectacle, and melodrama was both the mode and modus operandi of his statecraft. After the assassination of Marcoss arch political rival, Benigno Aquino, Jr., in August 1983, however, the freest press in Asia came alive after a decade

Marcoss rise to power and the 1986 popular revolt bring into relief a problem perennially addressed in the affective turn in the field of social movement studies: the deeply entrenched fear of mass action as the irrational exercise of mob psychology.

Berlant sees an affective public taking the place of the mythical rational public imagined at the center of classic accounts of U.S. citizenship. Challenging the Enlightenment view of rationality as the distinguishing trait of the human subject, the culture of true feeling holds that what makes us human is our ability to empathize with the suffering of others. Elevating compassion to a civic duty, the culture of true feeling is premised on the notion that subjects are emotionally identical in their pain and suffering and therefore imaginable by each other. As the glue that holds an affective public together, an emotional humanism presumes that to feel emotion x in response to injustice morally authorizes one to participate in the political sphere. Paradoxically, however, this brand of visceral politics locates political agency in private emotional acts.

Berlants concept of true feeling is a productive starting point for thinking about the poweras well as the pitfallsof political emotions in the two stories that I trace in this book. These stories are due for a critical reappraisal in light of a renewed interest in affect and emotion in the study of political cultures. Recent work on the Marcos dictatorship has indeed begun to explore the affective and emotional dynamics of political repression and dissent. Joyce Arriolas work on print culture and Rolando Tolentinos prolific writings on the cinema similarly see the conflict between Marcos and his critics in terms of a binary struggle between official and popular forms of nationalism, eliciting hegemonic and abject political feelings, respectively.Passionate Revolutions builds on these important developments in the field. As a focused study of the role of the press and the cinema in the rise and fall of the Marcos regime, it seeks to explain how political emotions operate in official and popular forms of nationalism, and how these two affective realms intersect in the interfaces between national allegory, melodramatic politics and sentimental publicity.

National Allegory, Melodrama, and Popular Struggle

What is the relationship between nationalist movements and their symbolic forms? Berlant has coined the term national symbolic to refer to the range of discursive resourcesicons, rituals, metaphors, and narrativesthat constitute a cultures shared language for constructing a collective consciousness. The national symbolic, in other words, activates public subjectivity in the realm of fantasy. Here, the fractured and depersonalized colonized subject is restored to state of wholeness by an affective act of identification with an imagined national body.

Marcoss many tracts on national culture echo Fanons polemic in Wretched of the Earth. Like Fanon, Marcos saw the importance of addressing the psychic wounds of the colonized subject, whose self-worth can be restored only via a program of cultural rehabilitation. This basic precept was the animus behind the regimes cultural policy (see ). Let me signpost the affective dimensions of this policy here. Briefly put, it is not enough to have a cultivated mind; the task of national regeneration requires the citizen to have a reeducated heart. It is up to the state, then, to create a national culture that would provide a space of emotional contact, recognition, and reflection for its citizens. As a dramaturgical mirror designed to reflect back to the citizen an image of her best self, this national culture will transform the citizen into a subject of feeling: someone with affective commitments to the regime and its fantasy of a national family.