THE KEGAN PAUL LIBRARY OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY

Jerusalem in History K. J. Asali

Ancient Civilizations and Ruins of Turkey Ekrem Akurgal

A Short History of the Saracens Ameer Ali

Alexander the Great E. A. Wallis Budge

The Technical Arts and Sciences of the Ancients Albert Neuburger

A History of the Hebrew People Charles Foster Kent

A History of the Jewish People, Vol. II James Stevenson Riggs

A Short History of the Saracens Ameer Ali

Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon Austen H. Layard

Annals of the Kings of Assyria E. A. Wallis Budge

Jerusalem in History K. J. Asali

Early Europe G. Hartwell Jones

The Technical Arts and Sciences of the Ancients Albert Neuberger

Excavations at Ur Sir Leonard Woolley

Jewish Life in the Middle Ages Israel Abrahams

The Mameluke or Slave Dynasty of Egypt, 12601517 William Muir

On the Trail of Ancient Man Roy Chapman Andrews

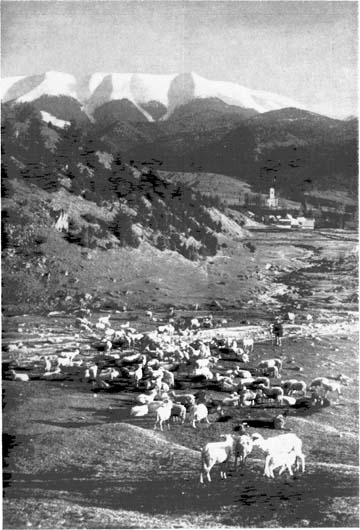

Peasant Europe H. Hessell Tiltman

The Kingdom of Georgia Oliver Wardrop

The Land of the Hittites John Garstang

First published in 2005 by

Kegan Paul Limited

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Kegan Paul, 2005

All Rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electric, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

ISBN: 0-7103-1155-9

ISBN: 978-0-710-31155-9 (hbk)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Applied for.

WESTERN EUROPE, preoccupied with the problems of international relations, industry, and the future of armaments, is sometimes in danger of overlooking the fact that more than half the entire population of that Continent is composed of peasants. The immense territories of this hundred millions of cultivators (outside the frontiers of the U.S.S.R.), whose bent backs till the soil of the ocean of peasant-lands, stretch from the Black Sea to the Baltic, forming a natural barrier between East and West. The peoples who inhabit that land of farmsteadsPoles, Ukrainians, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Southern Slays, and the resttogether represent the largest single unit in Europe, split by artificial political walls, but united by the bonds of common interests and, in war or peace, usually a common fate.

Those peasant territories remain to-day almost virgin soil for the world's manufacturers, populated by millions of potential customers clad in home-made clothing and living on the produce of their soil.

In this immense region governmental neglect, oppressive taxation, the fall in world agricultural prices, and political persecution in some of the most populous of the areas concerned first called a halt to development and then set the pendulum swinging back to conditions reminiscent of the serf-states of a century ago. That neglect and repression, unreported but nevertheless real, existed before the oncoming agricultural crisis left the peasant millions too poor to buy matches, salt, and oilthe three essentials of village lifeand will, unless the course of history changes, continue to exercise their baneful influence long after the world crisis has passed.

For generations the tillers of the soil, living far from civilization, were content to remain the dumb oxen of humankind. To-day an awakening is in progress, born of a growing consciousness of human and racial rights and quickened by a peace settlement which, while ostensibly based upon the principles of self-determination, denied all freedom and security to whole peasant nations such as the Ukrainians and Croats, while in other areas, such as Greater Rumania, minorities numbering millions were handed over, without consultation and against their wishes, to the care of nations a hundred years behind them in culture and development.

In the following pages are outlined the economic, political, and social conditions existing to-day in those peasant lands east and north of Vienna. Peasant Europe is based, not upon information thoughtfully revealed by the Press Bureaux maintained by governments, but on facts gathered during talks round the family tables of those who, born on the soil, see with the eyes and speak with the tongue of the peasant ; and who demand, not opportunities for migration, but consideration and decent conditions for themselves, their children, and their neighbours' children.

In an area divided by political barriers into seven states, and inhabited by some fourteen races with individual histories and in differing stages of development, conditions naturally vary. The highly organized agriculture of Hungary and Czechoslovakia finds little echo in the dwarf-farms perched high up on the Bulgarian hillsides or in the poverty-stricken villages of Serbia and the Old Kingdom of Rumania. Similarly, the main preoccupations of the thoughtful peasants in Eastern Europe are not Fascism, the fear of war, or the world depression, but the police regimes and calculated repression from which millions of themUkrainians, Croats, Slovenes, Hungary's Irredenta, the Bulgarians of the Dobruja, and other Minoritiessuffer under the uneasy peace.

These things, as I learned in those valleys and plains, occupy an even larger place in the thoughts of the peasant masses than the disastrous collapse of agricultural prices which heralded the worst agrarian depression in history. Out of them is coming a new unity and a revival of the dreams of that Green International of which the Bulgarian Stambuliski dreamed a decade ago.

In Yugoslavia, Macedonia, Rumania, and Poland I have met and talked with the leaders of peasant thought, whose aims and aspirations are outlined in these pages. Their names are suppresseda necessary precaution in writing of ideals and ideas for which hundreds have died since 1919, and many more now languish in the prison-cells of the countries named.

For the same reason I make only collective and anonymous acknowledgment here to the many individual peasants who received me into their homes, and who there, at meetings often attended by whole village communities, told me the story of their lives.