Preface:

One More River to Cross

One More River to Cross

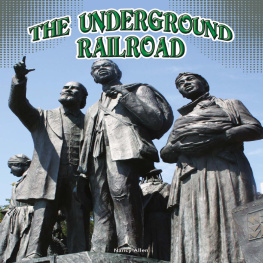

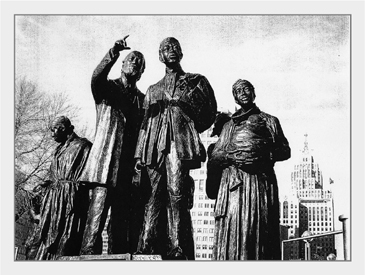

A t the center of One Hart Plaza in Detroit, Michigan, where United States land ends at the Detroit River, a group of larger-than-life-size bronze figures bear witness to one half of a shared story. Standing with them, following their gaze across the river, a few hundred yards away you can see Windsor, Ontario, in Canada, where the other half of the story took place and where similar figures are part of a companion monument. Even at first glance, both groups reveal the central fact in the story: On the U.S. side, the figuresmen, women, and children face north toward Canada, and from the look of them, you know theyre anxious to get there. Yet their anticipation is tinged with uncertainty and a vague weariness.

The monument in Windsor shows another group, this one newly arrived. Theyre being greeted and they seem thankful, if still hesitant and unsure of what awaits. Only one little girl, holding a doll, is looking back toward somethingor, more likely, someoneshe has left behind.

For a while during the nineteenth century, the city of Detroit had a code name: Midnight. Fugitive slaves passed through there in secrecy on their way to Canada, sometimes with the help of sympathetic contacts, but more often alone, with little information and without any assistance from others. In either case, they were always in danger. If they were lucky, there was aid on both sides. But what has come to be known as the Underground Railroad was less an organized system than a corridor of subterfuge and chance, and if there were sometimes conductors, safe houses, and tickets to ride, there were also arduous nights in the mountains and days in strange, threatening towns. There was no easy path out of slavery to freedom.

For those who made it to Midnight, the Detroit River became their Jordan, the one more river to cross theyd long sung about. On the other side lay their land of Canaan, and the liberty that still eluded Africans in the United States. For a period of time before the Civil War, even in so-called free states, fugitives could be hunted down and once more enslaved. But that did not stop thousands from running away.

From Windsor, the new arrivals traveled to several black settlements, among them one known as Dawn, where they lived freely under the protection of British law. There, in these places, the story continues. Before the Civil War, more than thirty thousand people crossed into Canada, many of them from Midnight to Dawn, some more than once as they returned to help others. Some of the fugitives who reached Canada stayed on after the Civil War; others returned to the States. But in the passage, all learned, through education and economic self-determination, the ways they might live free. Their story is neither a uniquely American story nor separately a Canadian story, but one that forever unites our two countries and people. It is a story of desperation and resistance, of courage and survival, of men and women who risked their lives in order to claim the life that they, and they alone, owned.

Communication among these settlers was common and considerable, with much travel from one location to another undertaken not only by residents but by interested visitors. The existence of a network of Canadian communities of escaped slaves and refugee free people of color was, of course, known in the United States; newspapers reported about them, abolitionist leaders referred to them. They did not all exist simultaneously during the half century before the Civil War, but large, small, separate or part of existing towns and citiesthey were familiar destinations to all the well-known figures, black and white, whose public positions against slavery inspired many. Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, John Brown, and Harriet Beecher Stowe all knew about, experienced, and wrote about Dawn, Wilberforce, Chatham, and the other places whose stories are told here.