Table of Contents

To my mother, Lois, for a lifetime of love and support

Foreword

The Vietnam War, which the United States joined in the early 1960s and abandoned in 1973, was and remains the most controversial struggle the country ever fought. The war had an even more searing effect in terms of its consequences and, most importantly, how the United States would act militarily to protect its perceived national security in the future. When the United States decided to enter the struggle, the country was engulfed in a wave of optimism, a spirit of Camelot produced by the electoral triumph of President John F. Kennedy. By the time the United States decided to withdraw from the conflict in 1973, the political careers of two presidents had been demolished and, in sharp contrast with the Kennedy era, the country was gripped by introspection, pessimism, massive protests over what many considered ten years of cruel and unjust war, and virtual paralysis in military thought generated by the countrys failure to prevail militarily in what most perceived as the new realm of unconventional warfare.

It is indeed ironic that when it reached its decision to intervene in Vietnam, the Kennedy administration did so at least in part because of a new military strategy it articulated to overcome frustrations produced by a previous warin this case the local but still bloody struggle in Korea from 1950 to 1953. Specifically, the strategy of Flexible Response, which the Kennedy administration implemented to replace the previous one of Massive Retaliation, which the administration believed contributed to the four-year stalemate in Korea, received its first test in Vietnam.

The Vietnam War, in addition to producing striking changes in the political landscape in the United States, also represented a watershed in American military thought. At the beginning of the 1960s the subject of conventional war, albeit in a nuclear context, dominated U.S. military thought. Unlike the strategy of Massive Retaliation, which deterred global nuclear war but left the United States clearly vulnerable to defeat in limited conventional war, Flexible Response seemed to promise victory in limited war. Thus, in part, President Kennedys decision to intervene in Vietnam resulted from the articulation of a new military strategy. In short, the Vietnam War became a testing ground for Flexible Response and for the new force structure of the U.S. armed forces.

When it became clear in 1973 that victory had eluded the United States in Vietnam, military analysts quickly concluded it was due to the U.S. military establishments failure to appreciate and prepare for a new type of struggle they termed unconventional or guerilla war. Supporting this analysis, political and military leaders in the Soviet Union, Cuba, and other peoples democracies bombarded the world with bold proclamations concerning the new realm of what they deemed partisan, unconventional, guerilla, or revolutionary wars.

In the wake of the Vietnam War, most U.S. and Western military and political pundits and historians concluded that the United States had suffered defeat because American armed forces failed to understand or cope with these new types of struggles. Citing the British armys experiences in Malaysia after World War II and many other instances, they generally agreed that the United States applied a strategy and tactics in the war suited to conventional limited or local warthat is, those suited to the newly articulated national military strategy of Flexible Responseto what was clearly an unconventional war.

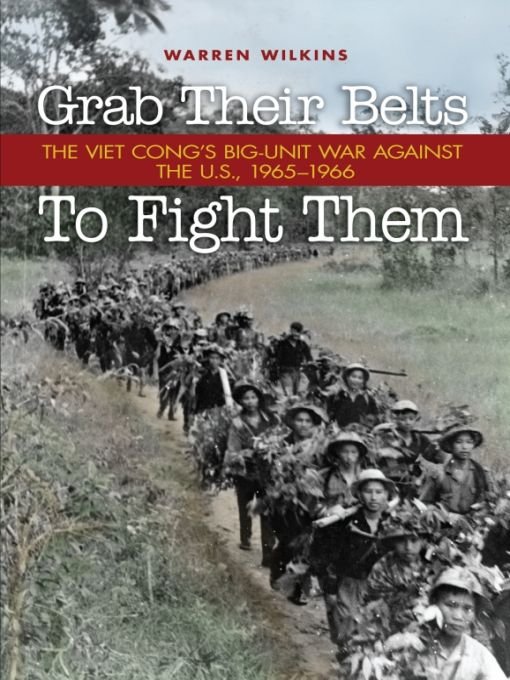

Unlike virtually all existing books about the Vietnam War, this one challenges previous studies by asserting that the conflict in Vietnam was not simply a classic unconventional clash of arms. Although it was always a hybrid armed struggle, Warren Wilkins demonstrates that during 19651966 the Communist Vietnamese forces emphasized a traditional big-unit approach to war with the United States and ARVN in an effort to achieve a quick and decisive victory.

This fresh approach, based on careful and extensive research, study, and analysis of North Vietnamese strategy and tactics, as well as the course of military operations in South Vietnam, presents an altogether different mosaic of the war. In short, it provides a new perspective and balance to a subject that, largely because it has been politicized, has sorely lacked both. It should be required reading for all interested in military history and past, present, and future military affairs.

David M. Glantz, Colonel, USA (Ret.)

Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I would like to thank God, for without Him I could never have negotiated the trials and tribulations this odyssey invariably entailed. While not divine, the support I received from my family, most notably my mother and my sister Andrea, also warrants my enduring gratitude. Indeed, no one championed this project more than Andrea.

As is customarily the case in most literary endeavors, this project profited immeasurably from the tangible support of numerous individuals. I am, for example, eternally indebted to Merle Pribbenow. Encyclopedic in his knowledge of our Communist adversary in Vietnam yet extraordinarily magnanimous with both his time and his resources, Merle translated and furnished scores of Communist Vietnamese histories, documents, and other research materials for use in this project. Merle, moreover, patiently answered question after question with remarkable specificity and thoroughness, and through our conversations and correspondences, succeeded in enhancing my understanding of Communist Vietnamese strategy and strategic thinking. Indeed, Merle served as a de facto mentor to me on this project.

Sgt. Maj. Dan Cragg, USA (Ret.), coauthor of the landmark tome Inside the VC and the NVA: The Real Story of North Vietnams Armed Forces, reviewed an early draft and provided invaluable editorial advice and much needed encouragement. Similarly, Lieutenant Colonel Otto Lehrack, USMC (Ret.), reviewed excerpts of subsequent drafts and dutifully embodied his daunting Marine Corps nickname of No Slack Lehrack, leaving this work the richer for it. Colonel Tom Faley, USA (Ret.), meanwhile, searched for and retrieved pivotal research material. And I would be shamefully remiss if I failed to acknowledge the profound impact and influence of Colonel David M. Glantz, USA (Ret.) on my development as a student of history in general and armed conflict in particular.

Additionally, many others deserve my heartfelt gratitude as well, including General P. X. Kelley, USMC (Ret.); Captain Ken Sympson, USMC (Ret.); Colonel Bill Haponski, USA (Ret.); Gary Hutchinson, USMC (Ret.); Tom Doc Stubbs, USN (Ret.); Gary Ball, USA (Ret.); Will Parish, USA (Ret.); Bill Baty, USA (Ret.); James Tobias, Center of Military History; Ashley Ekins, Head, Military History Section (Australian War Memorial); and Amy Mondt at Texas Tech University. I would also like to extend my thanks to Mark Moyar, Eric Bergerud, Martin Loicano, Marissa Sestito, Kil J. Yi, Lien-Hang Nguyen, Stephane Moutin-Luyat, and of course my intrepid editor at the Naval Institute Press, Adam Kane.