PHOTO BY ELLY BLUE

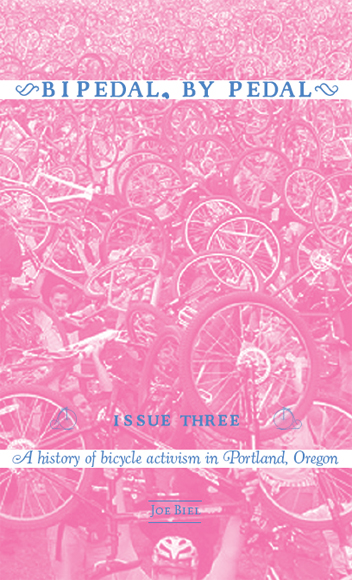

BIPEDAL, BY PEDAL

BIPEDAL, BY PEDAL

NUMBER THREE

A history of bicycle activism in Portland, Oregon

by Joe Biel

photos by Elly Blue

fonts by Ian Lynam

edited by Adam Gnade

designed by Joe Biel

First edition, January, 2012

ISBN 978-1-6210-6073-4

This was produced as a companion to the forthcoming documentary film, Aftermass: Bicycling In A Post-Critical Mass Portland. More info at:

CantankerousTitles.com

Number one is a $2 primer on the Critical Mass movement.

Number two is a $4 collection of police documents about the Critical Mass movement in Portland.

Additional copies of #3 can be had for $4 each.

All are available at MicrocosmPublishing.com

Or from:

Joe Biel

PO Box 14332

Portland, OR 97293

Contents

Some folks say that Portlands bike community has just moved beyond the need for such a ride and that it ignites more anti-bike sentiments than its worth. Others say it simply became a bore and an exercise in futility after the Portland Police instituted a very strict enforcement policy editorial, January 25, 2008, BikePortland.org.

Critical Mass, the monthly leaderless bicycle ride celebrated in cities around the world, ostensibly ceased to exist in Portland in 2007. Shortly before that The League of American Bicyclists awarded Platinum status to the city and Bicycling magazine named it the best place to ride a bike in the U.S. Bicycle street markings began to appear all over town in 2005 and difficult connections like bridges were finally redeveloped to accommodate cyclists. Bicycle commuters began to only risk their lives once or twice getting to work. Ridership was skyrocketing and people were talking about their interest in cycling as a reason they were moving to Portland. Mayoral candidates began campaigning on their bicycling interest. The mainstream advocacy organization, the Bicycle Transportation Alliance had a celebration citing accomplishment of their goals. People began saying that Portland had arrived.

Speculation and conjecture about Portlands Critical Mass have been bouncing around for years. The commonly adopted explanation became that Portland had moved beyond the need for Critical Mass.

But in 2007, with the departure of Critical Mass, street-level activism began to disappear. Advocates had become too comfortable, friendly, and at ease with city government. Bicycle development soon began to hit a point of stagnancy. Despite political will behind him, Sam Adams, Portlands bicycle-friendly mayor, was not receiving public support when needed and began to backpedal when he came under fire for catering to cyclists as a special interest group.

As bicycle funding increased, people turned out in droves to testify at city hall about the money being spent on cycling projects. The Oregonian, Portlands conservative daily newspaper, fueled the fire and challenged the citys embrace of bicycling. Despite the fact that a bicycle commuter pays for their road usage and necessary build-outs, and even leaves some of their tax money to be spent on car-centric projects, that doesnt prevent the pundits from claiming that people who ride bicycles are getting a free ride and not paying their way.

But what really happened to Critical Mass in Portland goes a little deeper. Four years ago I began tracking down the people who attended Critical Mass and retracing what happened to Portlands Critical Mass for work on the documentary film, Aftermass: Bicycling in a Post-Critical Mass Portland.

I wanted to know what it meant that Portland, one of the best North American cities for cycling, has virtually no Critical Mass. Was it no longer relevant, did its activity not appeal to a cycling mainstream, or was a police crackdown just that successful? What are the new goals of cyclists? What is the new activism? How are objectives reached?

Transportation bicycling in Portland got its first boost in 1971 when Don Stathos Bicycle Bill wrote into law that 1% of highway funding must be spent on pedestrian and bicycle projects. But it took until 1993 and a lawsuit from the Bicycle Transportation Alliance to actually make that happen.

In a 2005 interview, Roger Geller, the bicycle coordinator for the City of Portland, mentioned that the number one reason people cite for not cycling is safety, A lot of that has to do with motorist behaviorpeople driving too fast; people driving too aggressively; people driving unconsciously, not really looking. The thing to really encourage a lot more cycling would be to make the streets feel a lot safer.

Group bike rides like Critical Mass create that feeling of safety as well as statistically making the participants truly safer. Public health researcher Peter Jacobsen has proven that as more bicyclists are seen on the streets, motorists become familiar with how to behave around bicyclists and the rate of serious crashes decreaseseven the rate of cars crashing into other cars decreases.

Additionally, Transportation Commissioner Charlie Hales said, Critical Mass was important. It was out in the street making the point that bikes were a valid means of transportation. There were a lot of people who did not agree with that proposition. Theres a time in politics where its helpful to have someone else wave the big stick. The Bicycle Transportation Alliance and Critical Mass were hugely influential [in 1993].

Still, participants have almost universally described a feeling of a nervous edge and tension that is unique to Critical Mass and did not permeate through other bike rides in Portland. Yet there was often no distinction in the way Critical Mass behaved or how many participants it had. Roger Geller even cited similarities in the way that Portland Bureau of Transportation bicycle rides would move through stop signs as a group. During its decline, Critical Mass was attracting far fewer participants than police officers while many other rides were much larger. Where was this edge coming from?

In December of 1994, after a year and a half of peculiar tickets being issued for nonexistent violations at Critical Mass rides, longtime participant Fred Nemo helped organize 17 people into a class action suit in federal court. A year later they were awarded $50,000 and some documents that began to explain the tip of the iceberg about the origin of the polices harassment. Instead of referring to the group as Critical Mass, the police always dubbed them the Anarchist Bicycle Rally, which at the time was confusing and seemed to indicate bad intelligence on the part of the police.

The depth of discovery in these documents was a bit shocking. The discovery was also nothing new. Beginning in 1993, the Portland Police Department had been spying on Critical Mass through their Criminal Intelligence Division (CID). CID had been around since at least the 1950s and was originally dubbed The Red Squad. The city didnt admit that it existed for many years, but it spied on communists and undermined the political activities of its citizens. Similar in fashion to the tactics of the FBIs COINTELPRO, The Red Squad set out to discredit radical politics and protect the status quo. Over time it went through several rebrandings but its function remained similar. Michael Munk, author of

Next page