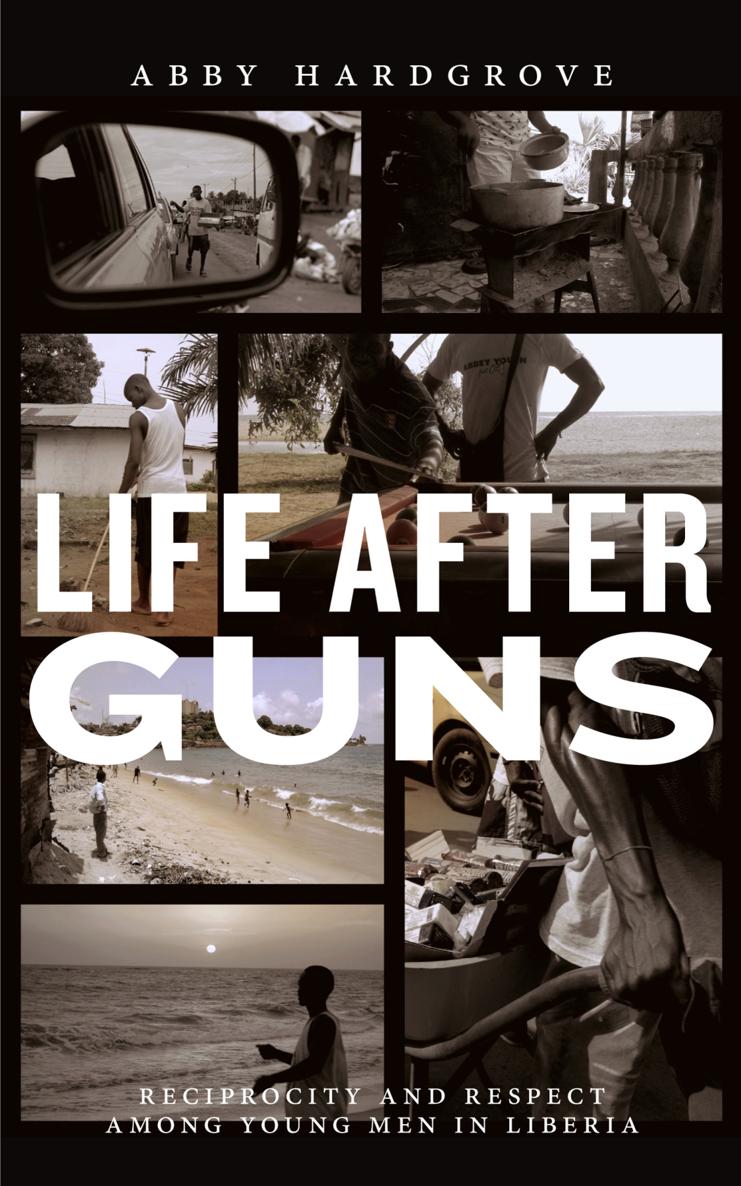

Life after Guns

The Rutgers Series in Childhood Studies

The Rutgers Series in Childhood Studies is dedicated to increasing our understanding of children and childhoods throughout the world, reflecting a perspective that highlights cultural dimensions of the human experience. The books in this series are intended for students, scholars, practitioners, and those who formulate policies that affect childrens everyday lives and futures.

Edited by Jill E. Korbin, Associate Dean, College of Arts and Sciences; Professor, Department of Anthropology; Director, Schubert Center for Child Studies; Co-Director, Childhood Studies Program, Case Western Reserve University

Elisa (EJ) Sobo, Professor of Anthropology, San Diego State University

Editorial Board

Mara Buchbinder, Assistant Professor, Department of Social Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Meghan Halley, Assistant Scientist, Palo Alto Medical Foundation

David Lancy, Emeritus Professor of Anthropology, Utah State University

Heather Montgomery, Reader, Anthropology of Childhood, Open University (UK)

David Rosen, Professor of Anthropology and Sociology, Fairleigh Dickinson University

Rachael Stryker, Assistant Professor of Department of Human Development and Womens Studies, California State University, East Bay

Tom Weisner, Professor of Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles

Founding Editor: Myra Bluebond-Langner, UCL-Institute of Child Health

For a list of all the titles in the series, please see the end of the book.

Life after Guns

Reciprocity and Respect among Young Men in Liberia

Abby Hardgrove

Rutgers University Press

New Brunswick, Camden, and Newark, New Jersey, and London

978-0-8135-7348-9

978-0-8135-7347-2

978-0-8135-7350-2

978-0-8135-7349-6

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2017 by Abby Hardgrove

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

www.rutgersuniversitypress.org

For those whose lives fill these pages and for those who read them. We are all students of our human condition and of the worlds in which we live.

Contents

AFL Armed Forces of Liberia

DDR disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration

DDRR Disarmament, Demobilization, Rehabilitation, and Reintegration program

ECOMOG Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group

ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States

LD Liberian dollars

LURD Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy

MODEL Movement for Democracy in Liberia

NGO nongovernmental organization

NPFL National Patriotic Front of Liberia

PAL Progressive Alliance of Liberians

ULIMO United Liberation Movement of Liberia

ULIMO-J United Liberation Movement of Liberia under Roosevelt Johnson

ULIMO-K United Liberation Movement of Liberia under Ahlaji Kromah

UN United Nations

Introduction

Theory, Fieldwork, and Storytelling

I began spending time on Bernards Beach in Monrovia during 2010, seven years after the final cease-fire that ended fourteen years of civil war in Liberia. The beach was usually quiet. Young men clustered under the coconut trees, out of reach of the sun, talking and smoking and passing the time. There was a pool table and some huddled around the games, taking small bets or waiting to play. Darlington was easy to spot among the others. Always clad in a sleeveless undershirt, shorts, and slippers (flip-flops), he cut a thin male figure, several inches shorter than me. When we met for the first time he informed me that he was security. He kept an eye out for any trouble on the beach as a favor to a friend. Though there were occasional kickbacks for his security work, he made most of his living selling rolled joints on the beach and in the neighboring area. He was a hustler, living on his own in a small room just off the main road. He talked to me at length about studying at a university, but had no money to pay for it. His life and prospects for the future were limited in scope, much like those in ethnographic accounts of other youth in Africa and around the world.

One afternoon while we were passing the time on the beach I asked Darlington to speak about the condition of the country for young men like himself. He sat back, joint in hand, and delivered an articulate analysis of the opportunities available to young people. It included a descriptive account of the implications of poverty, an evaluation of the governments failure to meet the needs of the peopleespecially the young peopleand the reasons beneath local crime and violence. The helping hand is not there, he finished. So many parents had died or lost the means to support their children, and there was little work. The helping hand is not there, he reiterated. This book is about the presence and absence of a helping hand in young mens lives, and what that means for their life chances, a phrase I borrow from Dahrendorf (1981) to indicate the options that people perceive based upon their social positions.

A helping hand might refer to a government program or a favor from a friend, but mostly, as Darlington used it, a helping hand meant the support of intergenerational relationships in families and kin networks. Family relations were a constant topic of conversation and concern for the young men in this book. Recent research in youth studies has ballooned with observations and theoretical interpretations about life chances, transitions, and trajectories. An interdisciplinary literature portrays urban young people in the Global Southbeen described as a crisis of youth (International Labour Organization 2013; Richards 1995). However, this book demonstrates that the marginalization felt by young people was not a generational crisis, but rather a crisis felt across generations, and one that had specific implications for young people. It provides an ethnographically grounded analysis of intergenerational hierarchies in Liberia, and illustrates how networks of reciprocal obligation organize social life, forming the foundation of support for young peoples lives and future possibilities.

I began this research out of an interest in the life chances of ex-combatants, specifically those who had fought when they were young. Half of the empirical material comes from the postwar experiences of ex-combatant young men. There are two dominant perspectives that inform much of the discourse about child soldiers: a rights-based narrative that emphasizes how damaging war is for children (see Machel 2001), and a security narrative that constructs former fighters as posing significant risks to postwar stability (see McMullin 2012). I traveled to Monrovia with two related assumptions about young people who live to tell their stories about fighting with armed groups. First, I assumed that they had been deeply affected by their experience, that trauma is a real thing, and that it has lasting impacts on how people live their everyday lives. There is now an enormous amount of research concerned with trauma in the aftermath of war. I conducted this work under the assumption that everyone had been affected by the war, and that while trauma is part of postwar life, it is not the sum total. I have left the analysis of trauma to psychologists and their critics and pursued an ethnographic description of youth experience in the social landscape of the postwar city. Second, in regards to the security narrative, I assumed that ex-combatants