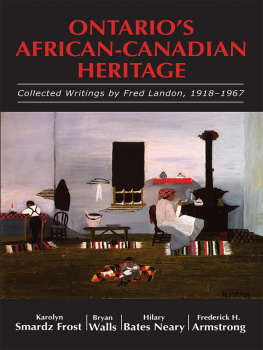

The Reverend Jennie Johnson and

African Canadian History, 1868 1967

Winner of the Ontario Historical Societys 2013 Alison Prentice Award, which recognizes the best book on womens history in Ontario published in the past three years.

After her conversion at a Baptist revival at sixteen, Jennie Johnson followed the call to preach. Raised in an African Canadian abolitionist community in Ontario, she immigrated to the United States to attend the African Methodist Episcopal Seminary at Wilberforce University. On an October evening in 1909 she stood before a group of Free Will Baptist preachers in the small town of Goblesville, Michigan, and was received into ordained ministry. She was the first ordained woman to serve in Canada and spent her life building churches and working for racial justice on both sides of the national border.

In this first extended study of Jennie Johnsons fascinating life, Nina Reid-Maroney reconstructs Johnsons nearly one-hundred-year story from her upbringing in a black abolitionist settlement in nineteenth-century Canada to her work as an activist and Christian minister in the modern civil rights movement. This critical biography of a figure who outstripped the racial and religious barriers of her time offers a unique and powerful view of the struggle for freedom in North America.

Nina Reid-Maroney is Associate Professor in the Department of History at Huron University College at Western (London, Ontario) and a coeditor of The Promised Land: History and Historiography of Black Experience in Chatham-Kents Settlements

The Reverend Jennie Johnson tells the story of a remarkable figure whose varied accomplishments represent an important legacy for black history in Ontario and an example for womens rights. Reid-Maroneys account of Johnsons long life moves from the Underground Railroad era into the later, seldom explored time period that followed. Beautifully written and thoroughly researched. Bryan Prince, author of One More River to Cross and A Shadow on the Household.

Gender and Race in American History

Alison M. Parker, The College at Brockport, State University of New York

Carol Faulkner, Syracuse University

ISSN: 2152-6400

The Men and Women We Want

Gender, Race, and the Progressive Era Literacy Test Debate

Jeanne D. Petit

Manhood Enslaved: Bondmen in Eighteenth- and

Early Nineteenth-Century New Jersey

Kenneth E. Marshall

Interconnections: Gender and Race in American History

Edited by Carol Faulkner and Alison M. Parker

Susan B. Anthony and the Struggle for Equal Rights

Edited by Christine L. Ridarsky and Mary M. Huth

The Reverend Jennie Johnson and African Canadian History, 1868 1967

Nina Reid-Maroney

Acknowledgments

In following Jennie Johnsons complex religious associations, I was grateful for the guidance of archivists and librarians at the Canadian Baptist Archives, Wilberforce University Archives, the libraries of Central State University and Payne Theological Seminary, and the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, all of whom helped to clarify the twists and turns of denominational records. In addition, I received invaluable assistance from staff at the Archives of Ontario; the Chatham Kent Public Library; the Ontario Genealogical Society (Kent Branch); the Verschoyle Phillip Cronyn Memorial Archives of the Diocese of Huron; the Historical Society of Pennsylvania; the Knox County Public Library, Vincennes; Oberlin College Archives; the University of Saskatchewan Library, and the Archives and Special Collections at The University of Western Ontario. When I turned to local research for the project in the summer of 1999, Gwendolyn Robinson of the Chatham Kent Black Historical Society kindly introduced me to Mr. Glen Ladd of the Prince Albert Baptist Church. Mr. Ladd transformed his living room into a research library and produced the earliest record books of the Second Union Baptist Church, Chatham Township (later Prince Albert Baptist Church), along with genealogical files and other materials including his own recollections of Jennie Johnson. Mr. Ladd has since passed away, but I remain in his debt for sharing documents that would never have come to light without his help, and for the welcome he extended to our family in a worship service at Jennie Johnsons church. The Reverend Dale Bowman of Flushing, Michigan, generously provided detail and insight that I would never have known otherwise, regarding Johnsons friendship with George and Clara Vercoe of Flints North Baptist Church.

A Mark Gillette research fellowship at the Bentley Historical Library and a term as a visiting scholar at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan both provided invaluable support, as did colleagues and students in Womens Studies and in the Department of History at the University of Windsor. Alison Templer provided research assistance at an early stage in the project. Since then, colleagues past and present at the Huron University College, students in History 3311F and 3313G, and friends in Hurons Faculty of Theology have been unfailingly generous in their encouragement and comments on the work. Although the research and writing of this book predated the Promised Land Project (a Community University Research Alliance funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada, 200712), the Promised Land familyDevin Andrews, Wanda Thomas Bernard, Boulou Ebanda de Bbri, Claudine Bonner, Marie Carter, David Divine, Olivette Otele, and Handel Wrightprovided collegial and lively support for other aspects of my research, and reminded me of the wider importance attached to the telling of one womans story from the promised-land communities of nineteenth-century Canada.

Bryan Prince of the Buxton National Historic Site and Museum drew my attention to the remarkable photograph and biographical notice that Jennie Johnson supplied to Rev. D. D. Buck, author of the 1907 volume, Progression of the Race . The other photographs of Johnson are in the Canadian Baptist Archives, McMaster University, and I appreciate the permission to use them in this work.

At the University of Rochester Press, editorial director Suzanne Guiod and series editors Alison Parker and Carol Faulkner offered incisive readings of the manuscript that paved the way for the voice of Jennie Johnson to come through more clearly. I am grateful to them, and to Ryan Peterson, Julia Cook, and the copyeditors at the Press, along with the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript, for their suggestions and insight.

The work has benefitted immeasurably from the support given by so many who shared the sense that Johnson deserved a fresh audience. The importance of the work comes from its subject; the shortcomings of the work are entirely mine. Literary scholar Hermione Lee has argued that life writing, like the experience that furnishes its materials, will always be made up of contested objectsrelics, testimonies, versions, correspondences, the unverifiable. Until now, Jennie Johnson has been left so far out of the historical record that there is progress, surely, in the act of restoring her life story to the realm of things contested. My hope is that this book has effected such a restoration, without cracking open too many reliquaries along the way.