Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

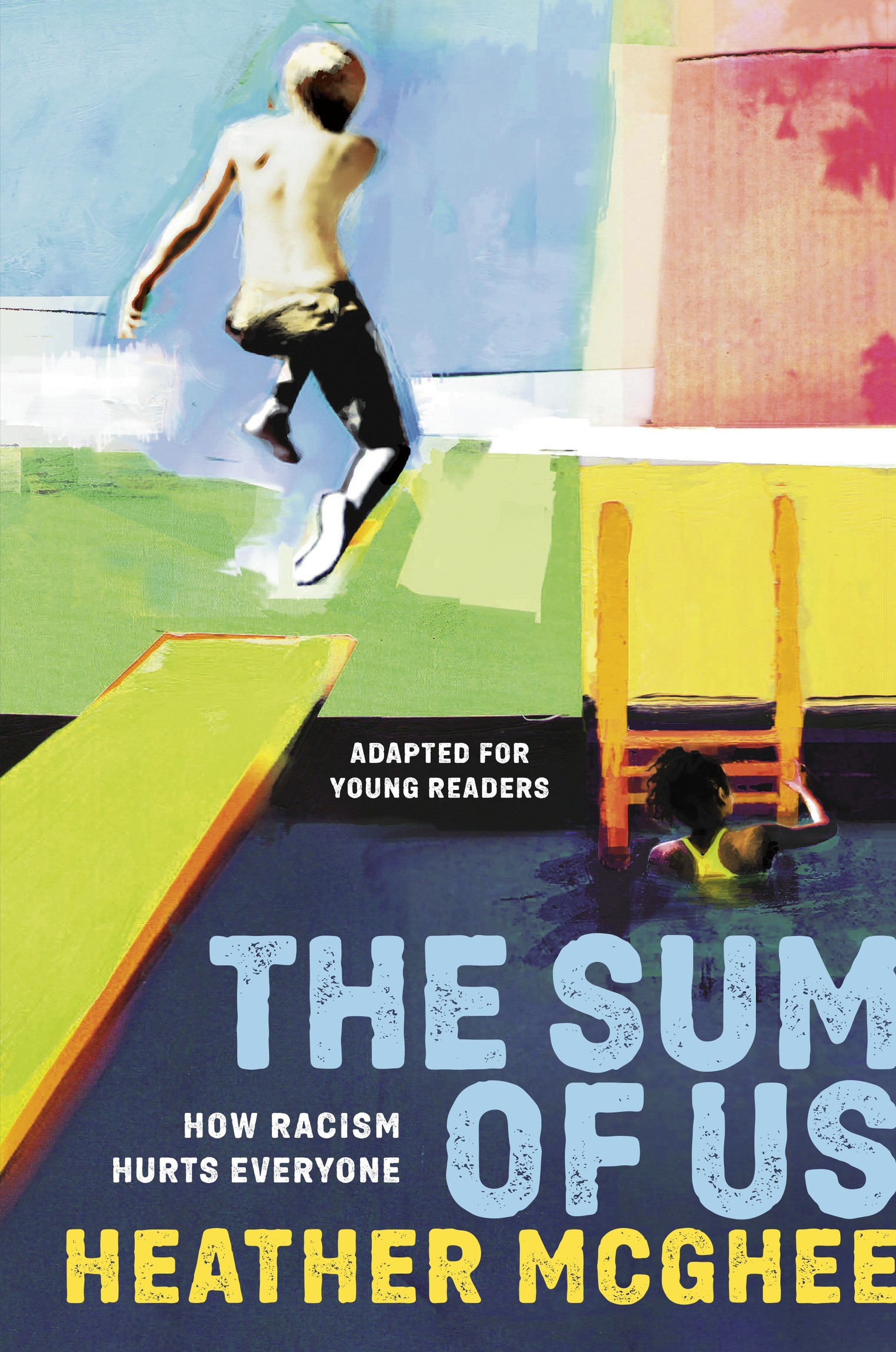

The Sum of Us is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Text copyright 2023 by Heather McGhee

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

This work is based on The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, copyright 2021 by Heather McGhee. Published in hardcover in the United States by One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, in 2021.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! rhcbooks.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022948140

ISBN9780593562628 (trade) ISBN9780593562635 (lib. bdg.) ebook ISBN9780593562642

Cover art by David McConochie

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

Penguin Random House LLC supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to publish books for every reader.

ep_prh_6.0_142492539_c0_r0

FOR MY MOTHER

Contents

_142492539_

INTRODUCTION

Why cant we have nice things?

Have you ever asked this question? By nice things, I dont mean hovercraft or laundry that does itself. I mean the more basic aspects of a high-functioning society, like a great public school in every neighborhood, debt-free college education, affordable health care, jobs that keep people above poverty. The we who cant seem to have nice things is Americans, all Americans. This includes the white Americans who are the largest group of the uninsured and the impoverished. Americans of color are disproportionately impoverished and uninsured as well. We is all of us who have watched generations of American leadership struggle to solve big problems and reliably improve the quality of life for most people. We know what we needwhy cant we have it?

Why cant we have nice things? was a question that struck me pretty early on in lifegrowing up in an era of rising inequality, seeing the wealthy neighborhoods boom while the schools and parks where most of us lived fell apart. I went on to a career in public policy advocacy, using statistical research, congressional testimony, legislative drafting, and talking to the media to advocate, basically, for more nice things for more people. I felt like I was fighting the good fight in a country where one percent of the population owned more wealth than the entire middle class while half of adult workers were paid too little to meet their basic needs for things like housing and food. But we werent making progress fast enough, and so I decided to hit the road to find out what was holding us back.

What I found is that there are hidden costs of racism to all of us. I traveled to Mississippi and sat with factory workers trying to unite a multiracial workforce to bargain collectively for better pay and benefits. I talked to white homeowners who had lost everything in a financial crisis sparked by predatory mortgages that banks first created to strip wealth from black and brown families. I heard from white parents and students who feared that segregated white schools would render them ill-equipped for a diverse world. To understand when the majority of white Americans had turned against government solutions, I traveled to one of the many towns that had drained its public swimming pool rather than integrate it.

I didnt set out to write a book about history, but my journey revealed that a people who have been robbed of their history can be manipulated by the same forces generation after generation. Did you know that in a recent survey, less than ten percent of high school seniors could accurately say that slavery was the primary cause of the Civil War? I met a white suburban mother named Rachel who told me about her outrage that even though shed been educated in Oklahoma public schools her whole life, she had only recently learned about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. She recalled seeing a black Tulsa neighborhood as a child and having no answer for why it seemed so poor. In the absence of history, negative stereotypes filled the void. What if people had been taught about why black communities were so marginalized? she asked, her anger audible. A chance to fully understand something was taken away from me because I didnt learn about this moment. There was this flourishing black community and we were never aware of it, because that history was robbed from me. Learning about racist episodes in history isnt racist; its essential to erasing racism from our future.

To this day, a self-interested elite is trying to rob us of our shared history, hoping to keep people who have a lot in common from rising up together. But not everyone is buying it. Everywhere I went, I found that the people who had linked arms with others across racial lines had found the key to unlocking what I began to call a Solidarity Dividend, from higher wages to cleaner air, made possible through multiracial collective action.

Nothing about our situation is inevitable, but you cant solve a problem with the same consciousness that created it. The outdated belief that some groups of people are better than others distorts our politics, drains our economy, and erodes everything Americans have in common, from our schools to our air to our infrastructure. Join me on a journey to understand how this idea came to be so powerful and how a new generation of cross-racial movements are working to end it, once and for all.

When I was growing up, my family and my neighbors were always hustling. My mother had the fluctuating income of a person with an entrepreneurs mind and a social workers heart. My dad, divorced from my mom since I was two, had his own up-and-down small business, too, and soon a new wife and kids to take care of. If we had a good year, my mom, my brother, and I moved into a bigger apartment. A bad spell, and Id notice the mail going unopened in neat but worrisome piles on the hall table. I now know we were in what economists call the fragile middle class, all income from volatile earnings and no inherited wealth or assets to fall back on. We were the kind of middle class in the kind of community that kept us a stones throw from real poverty, and I think this shaped the way I see the world. My mother took us with her to work in Chicagos notorious Robert Taylor public housing projects while she gave health lessons to young mothers, and some of my earliest playmates were kids with disabilities in a group home where she also worked. (It seemed she was always working.) We had cousins and neighbors who had more than we did, and some who had far less, but we never learned to peg that to their worth. It just wasnt part of our story.