Copyright 2015 by Sandhya Rani Jha.

All rights reserved. For permission to reuse content, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, www.copyright.com.

Bible quotations marked NRSV are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked ESV are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version (ESV), copyright 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked (NIV) are taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION. NIV. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved.

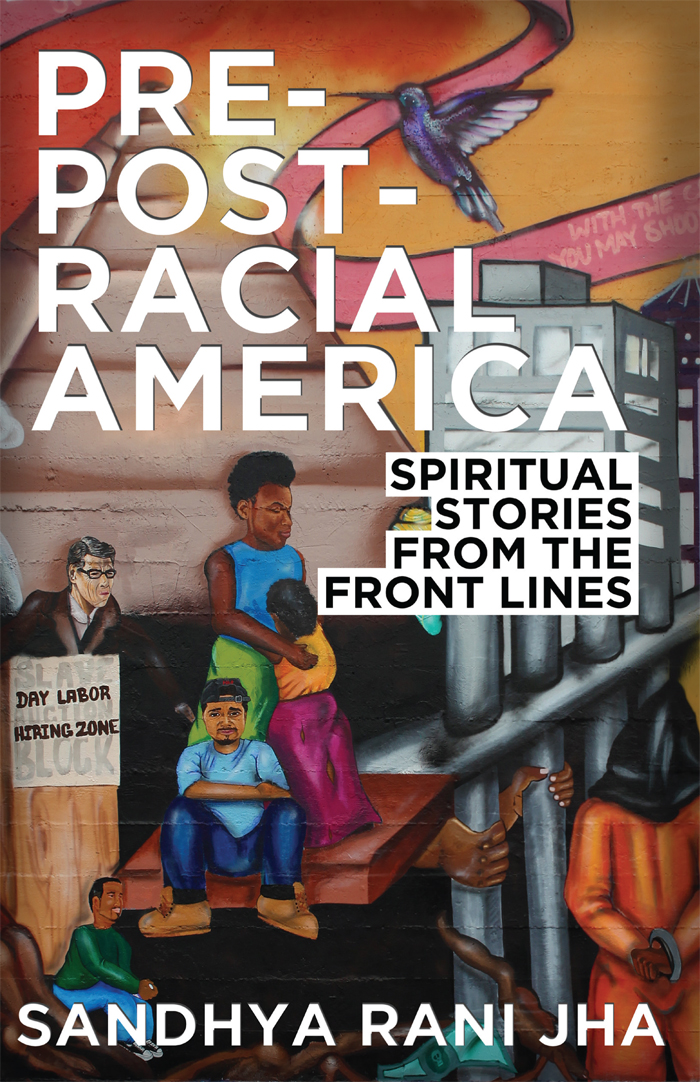

Cover art: Portion of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings mural at 86th Avenue and International Boulevard in Oakland, California. The aerosol and acrylic mural was created by participants in 67 Sueos under the direction of lead artist Francisco Sanchez. Photograph of mural is by Jesus Iniguez. The Black/Brown Unity Mural was funded by Creative Works and done in collaboration with Allen Temple Baptist Church. Copyright 2014 by 67 Sueos, a program of the American Friends Service Committee. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Photo of Sandhya Rani Jha by Alain McLaughlin.

Print: 9780827244931 EPUB: 9780827244917 EPDF: 9780827244924

www.ChalicePress.com

Our goal is to create a beloved community and this will require a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives.

REV. DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to my incredibly gifted (and sensible) mother, Janette Jha, for helping create the questions at the end of each chapter as well as (alongside my equally gifted and sensible father Sunil Jha) having raised me with my faith and my interest in hearing multiple stories. Additional thanks to the many people of diverse backgrounds who helped me with the outline, chapter content, and fine-tuning my content; crowdsourcing is awesome! (Particular thanks to Riana Shaw Robinson, Derek Penwell, Yuki Schwartz, Ayanna Johnson, and Kat Hussein Lieu for feedback on large chunks of the draft manuscript.) Most of all, thanks to the inspiring people whose stories populate this book. I am grateful that you help me be a better person and make the world more and more the Beloved Community.

I would not see the world the way I do were it not for the Reconciliation Ministries of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) or Crossroads Antiracism Organizing & Training. Although most of my work is done in local community today, I thank God for both of them from the bottom of my heart.

INTRODUCTION

Complicating the NarrativeStories of Living Race in America

Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story and to start with secondly. Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story.

CHIMAMANDA ADICHIE,

THE DANGER OF THE SINGLE STORY,

TED TALK, OCTOBER 7, 2009

My parents met at a college dance at Glasgow Tech in Scotland. I like to imagine their first dance was to a Beatles song, although I have no evidence to that effect. I just really love the Beatles, and they met in the fall of 1964.

My father was ten years old when India got its freedom and remembers taking turns with his classmates as night watch, sitting on the roof of the school in his village as they protected themselves against possible attacks in the wake of the bloody partition battles that broke out on August 17, 1947. My mother was born in post-war Glasgow, Scotland, and lived with ration coupons well into the 1950s. Interracial relationships were not much beloved when they met in 1964. My parents werent political, and they didnt have a profound civil rights agenda. They just didnt care about the potential controversy; they liked each other. And eventually they loved each other.

So they weathered my mother being rejected by her family for loving a man of a different race and religion because they loved each other. And they weathered my fathers familys deep ambivalence about my mother because they loved each other. (Today the family in India says he did even better than an Indian wife, because my mother has been so fiercely loyal to them.) And they didnt worry too much about the petition to evict them from the neighborhood when they first bought a home together, because they loved each other. And forty-five years since their wedding (fifty years since they met), they still love each other. And, better yet, they still like each other.

So my baseline narrative for race relations is a pretty inspiring one. But it is not uncomplicated.

Its complicated by my familys religious diversity: my father is Hindu and my mother and I are Christian. Its complicated by growing up on the outskirts of Akron, Ohio, where the five kids of color in my class of two hundred all strove to be as standard American as we were allowed to be, and since there were so few of us, we were pretty well accepted as long as we didnt claim any sort of difference. My school existence was complicated by hanging out with the Bengali Indian community on weekends, where the kids all ate pizza and watched football while the adults ate curry and talked politics. Its complicated by finding my voice as a South Asian in a suburban Chicago high school when I made friends with other South Asians while simultaneously being light-skinned enough to be mistaken for Greek, Latin@, Middle Eastern, Eastern European, and only very rarely identified as South Asian. And even that is complicated by the fact that for those who meet me in writing first bring a whole set of assumptions about who I am before we meet face-to-face. (This can be messy both in my consulting work and in online datingyou would not believe what some American men assume about South Asian women that meeting me in person cannot seem to disrupt.)

And yet my experience of race is very different than my parents. My father, raised in a village where he was the same as everyone else, is sent to Toastmasters by his boss for not being a good public speaker, and when the head of Toastmasters says, I dont know why youre hereyoure a great public speaker, my father thinks, Oh wellToastmasters is fun! instead of thinking, That was about my accent, wasnt it?

My mother hears a person at the luggage store where she works say, I wish [all Indians] would go home, and she thinks its a story worth telling over dinner but doesnt waste her time getting in the face of someone so ignorant in the moment, and doesnt give it more thought than that.