This introductory chapter provides a broad-brush presentation of the intergovernmental regime for sustainable development that has arisen since the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also known as the Rio Earth Summit, and beyond. The chapter begins with an outline of the origins of sustainable development as an intergovernmental and international policy agenda and delineates some of the main outcomes arising from UNCED. These include the various conventions guiding global environmental policy today, as well as the Global Environment Facility, one of the most significant channels of finance for sustainable development. Also explored are the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), 20002015 and their successors, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This is followed by a discussion of the role of the private sector in financing sustainable development and the challenges inherent in unlocking private finance. The chapter continues with an exploration of the future for sustainable development and finance in the light of the alternative approaches to understanding and valuing capital and in the context of COVID-19. A final section summarises the contributions of the various authors in this section, who explore a range of issues confronting the current practice of, and potential for, sustainable development and finance.

Keywords: ecosystem services, forest certification, global environment facility, landscape planning, millennium development goals, natural capital, neoliberalism, sustainable development goals, unced, taxonomy, world bank, COVID-19,

Sustainable development as an intergovernmental and international policy agenda

The current agenda for sustainable development and finance, however it has developed, is a child of global cooperation around environmental problem-solving in an era when the collapse of the Soviet Union reinforced the belief in progress towards a world of democratic, liberal internationalism. Communism was largely confined to China and capitalism was the dominant economic system. Recent environmental initiatives of the time, such as tackling the hole in the ozone caused by industrial chemicals, demonstrated how world governments could come together to develop policies and agreements in favour of the common good. Environmental problems ).

At the heart of UNCED lies Agenda 21 ().

One of the fundamental orientations of Agenda 21 was (and is) its emphasis on the use of market mechanisms to deliver sustainable development ().

As the 1990s receded and gave way to the new century, the expectations for truly sustainable development began to fade. In that sense, the Millennium Summit of 2000, its Declaration and the MDGs 20002015 represent an effort to revisit the ongoing and unmet needs for human development and poverty eradication, despite three decades of development (.

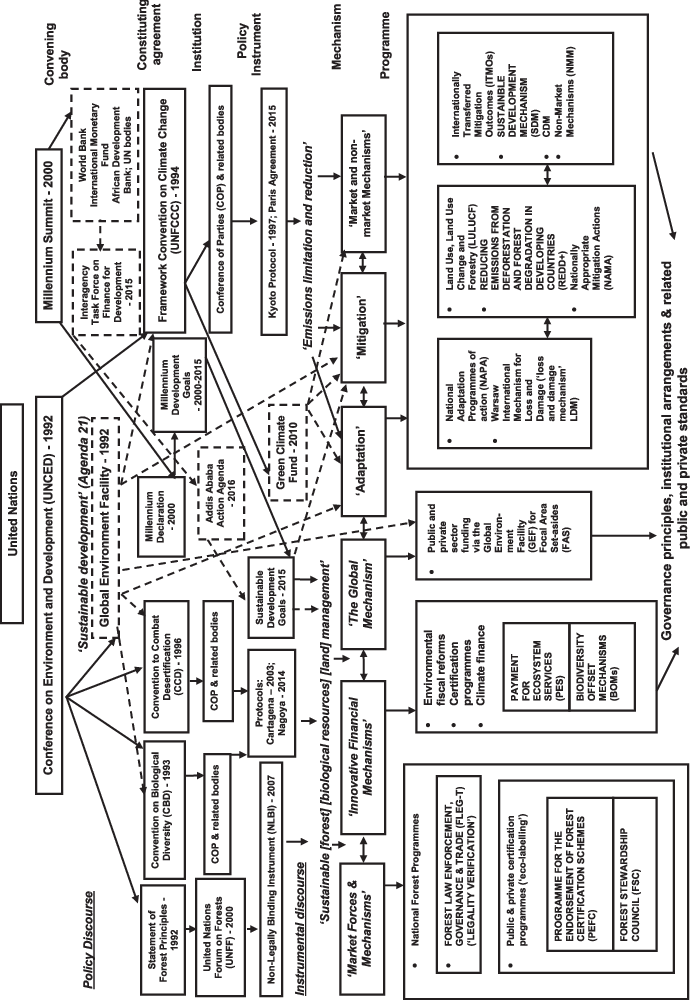

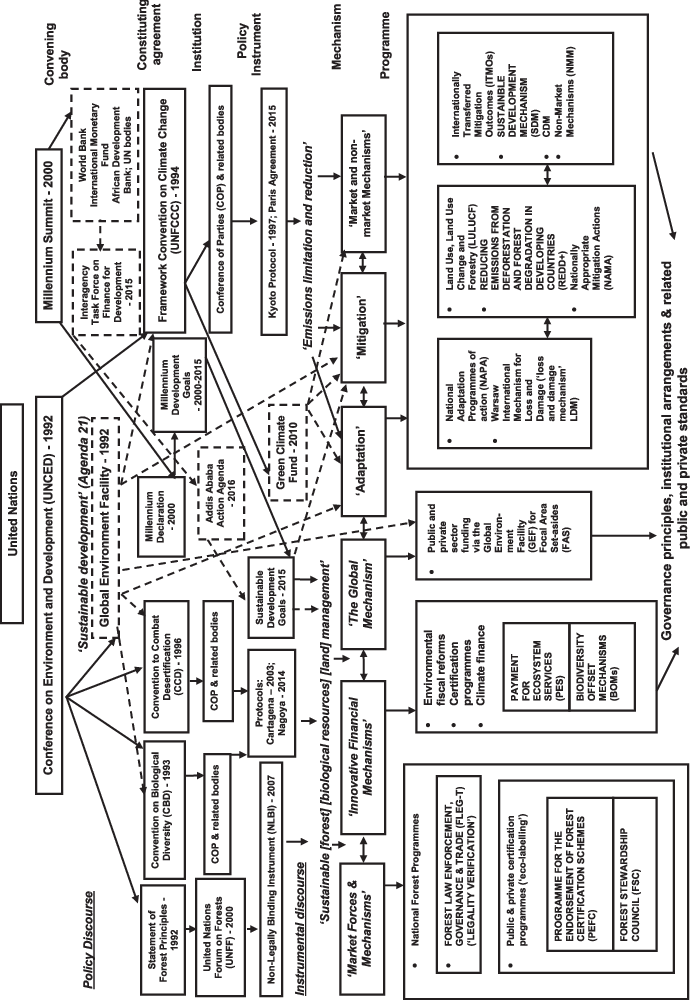

Source: , adapted with permission.

Note: Stippled lines indicate finance flows.

Figure 1.1: The regime complex of sustainable development and finance.

The role of the private sector in financing sustainable development

In reality however, there is still little incentive for private sector transformation from business-as-usual practices. If these initiatives are to be scaled-up globally to achieve climate targets and development goals, alternative options must be explored that could unlock further funding. Rather than relying on public investments in these initiatives, which often involve private partners utilising instruments such as deferred loans government guarantees, or other mechanisms offering favourable terms can provide solutions that will be repaid and thus carry greater impact or exist as part of larger programmes where profits are reinvested. Establishing government stability and support for sustainable natural resource management are likely to increase private sector investment and foreign direct investment. Undervalued natural assets ). This has led to unsustainable management at the landscape level and new approaches are required to build landscape planning and sustainable finance into business practice. This is explored by Edward A. Morgan and Andrew Buckwell in Chapter Five.

The past decade has seen a burgeoning interest in scaling-up private investment to address persistent socioeconomic and environmental challenges globally (). To transform the global energy complex to be carbon neutral within a time frame designed to prevent irreparable damage to the environment presents unprecedented challenges. The private sector must deploy financial, material and engineering resources on a scale never before undertaken with the government providing leadership, removing barriers and supporting industry efforts through policies that mobilise markets to achieve environmental objectives.

The Sustainable Development Goals and targets are interdependent one with another ().

There are examples of emerging economies which show the significant contribution private financing can make to achieving sustainability (); such systems now need to emerge within domestic economies to amplify sustainable business.

Private sector participation in green finance and investment can provide an opportunity for development in numerous sectors of the economy (). Global actors including countries, regions, cities, companies, investors and other organisations are also willing to report their commitments to act on climate change, with private governance reporting mechanisms such as the Carbon Disclosure Project (NAZCA: Global Climate Action Portal Undated). This is a positive sign for economic transparency in the emerging global green economy. To unlock private finance, variations in the current systems are essential to incentivise private investment in sustainable behaviour. Free market logic and capitalism should result in an orderly allocation of capital with the proportionate blending of the private and public sectors. But this seldom happens in reality. Expecting transformational change from increasing these types of investments when they coexist with business models, financial systems and government policies that incentivise the very actions and activities responsible for the environmental damage humanity is trying to rectify is radically unrealistic.

The future for sustainable development and finance

Capitalism has speciated as a consequence of Rio and the sustainable development agenda ().

The global pandemic poses its own challenges to sustainable development and finance. Health, social inequality and other aspects of sustainable development targeted by the SDGs have all been affected by the pandemic. While the impact of the pandemic has been negative on many aspects of society, the potential of the virus to transform society has also been noted. Business-as-usual may reassert itself post-pandemic, leading to an increase in emissions, as industry and consumers seek to make up for lost opportunities (). As several authors in this Handbook note, the disruption brought about by COVID-19 also provides a unique opportunity to galvanise the global economy through public and private finance for sustainable development. Whether this happens remains to be seen.