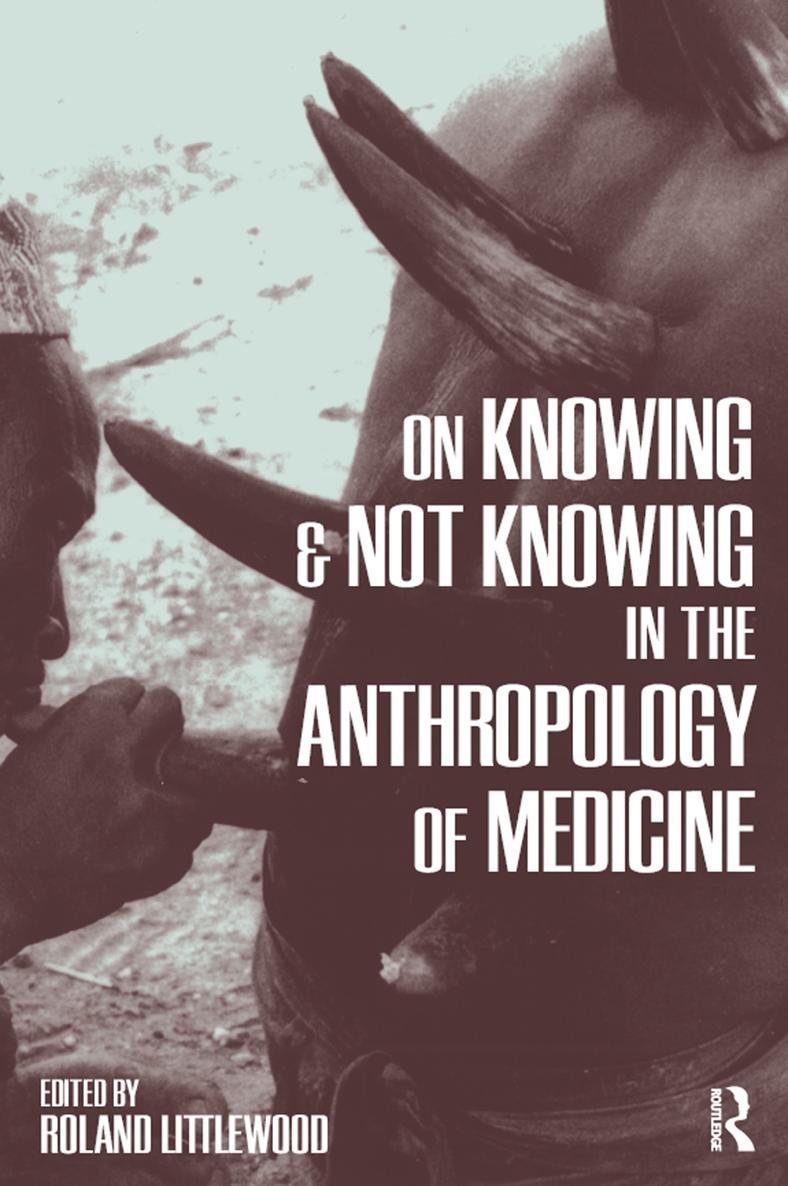

ON KNOWING AND NOT KNOWING IN THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF MEDICINE

ON KNOWING AND NOT KNOWING IN THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF MEDICINE

Edited by Roland Littlewood

First published 2007 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2007 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Chapter 4 is a revised and extended version of the following article: S. Dein, Against Belief: The Usefulness of Explanatory Model Research in medical Anthropology, Social Theory and Health 1, no. 2 (2003): 149162.

An earlier version of parts of chapter 7 appeared in the Journal of East African Studies 1 (1).

Library of Congress Cataloging-In-Publication Data

On knowing and not knowing in the anthropology of medicine/edited by Roland Littlewood.

p.cm.

Includes bibilographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59874-274-9 (hardback: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-59874-275-6 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Medical anthropology. 2. Traditional medicineCross-cultural studies. I. Littlewood, Roland.

GN296.O5 2007 306.4'61dc22 2006035240

Cover design by Joanna Ebenstein

Cover photo: This photograph shows the Hausa version of cupping (Kaho) using cattle horns and suction to draw out dead blood which builds up, they say, during hard farmwork under a hot sun. Murray Last

ISBN 13: 978-1-59874-274-9 hardback

ISBN 13: 978-1-59874-275-6 paperback

These essays are published in Honor of Murray Last

Contents

Roland Littlewood

Murray Last

Roland Littlewood

Gilbert Lewis

Simon Dein

Guido Giarelli

Sjaak van der Geest

P. Wenzel Geissler and Ruth J. Prince

Ren Devisch

Vieda Skultans

Els van Dongen

Pamela Reynolds

David Parkin

ROLAND LITTLEWOOD

As an offspring of the discipline of social anthropology, contemporary1 medical anthropology tends to follow only somewhat laggardly the theoretical fashions of its parent. Ten or twenty years after anthropologists became anxious about their generalizing on the culture of the X or the kinship system of the X (or indeed the X themselves), similar concerns are now manifest in medical anthropology. Does a society really have its own unique medicine? Is any medical system which we might observe to be found in the minds of individual members of that community, or can it be said to be located in that society as a whole, or is it merely our convenient way as external observers of collecting together and describing health- and illness-related practices? Whose systematization produces the system, the locals or that of the ethnographers?

Anthropologists, sociologists, and health educators alike have assumed that systems of medical knowledge held by indigenous peoples and by Westerners alike are generally uniform and consistent, and are accessible to the observer or student. Over the last few years it has become evident that this is hardly so: frequently, members of social groups and their healers alike do not have a clearly established rationale for health beliefs and medical practices that could be represented as a system. In the extreme case, local treatments are seen as efficacious precisely because their mode of operation is mysterious or even unknownMalinowskis coefficient of weirdness. For [c]ultures do not simply constitute webs of significance [they] are webs of mystification as well as signification.2

This book collects together some recent work in medical anthropology that argues that there are limits to the coherence of local health-related knowledge, whether in the mind of the informants themselves or in the analytical models of the anthropologist. And this has epistemological consequences more generally for local knowledge and external analysis. Among our themes then are:

What of locally nontheorized medical practice: are our generalizations to be based solely on our systematizing observations, or are they really there in the heads of our informants?

What of the possible local absence of explanatory schemata of sickness?

What are the limits of our possible knowledge, and the constraints upon certain accepted types of research?

Our chapters take their impetus from a significant paper published by Murray Last in 1981, and presented as in a slightly revised format. In The Importance of Knowing about Not Knowing, he argued that there is usually an uneven distribution of knowledge in a society, and that frequently for anthropological observers it is layered, becoming ever less certain the deeper we get into it. But some alternatives are more central than others, more closely bound to the central ideology or central system of economic relations, leaving those practices at the bottom of the hierarchy much less systematized than those above, with their patients and practitioners having a less formal set of ethnomedical ideas.

Lasts research over the last thirty-five years has been carried out among the predominantly Muslim Hausa-speaking people of northern Nigeria. At the top end of local medical practice lies the biomedicine of the local university hospital, together with that of various Christian missionary dispensaries. At the other, traditional, end are local Maguzawa healing practices, and in the middle we find Islamic medicine, based on Arabic texts, overlapping both top and bottom. Traditional healers deal with a variety of complaints, with fortune-telling and the provision of poison, and also with the mentally ill; their practices include the somewhat unsystematized possession rituals, as well as involving specialists such as herbalists, midwives, bonesetters, and barber-surgeons. They have to compete with both local people who might have some special technique or cure and with healers from outside the area who come to offer their skills to the local population.

What Last terms a system of local ethno-ecology argues that each cultural group has its own particular illness and particular cures. So a stay in the hospital may by itself be quite inadequate for these local illnessesor indeed even prove actually dangerous, for it is there that the Europeans devise their own magic. One consequence is that there may be no general areas of agreement between different healing groups on terminology. What may seem to be the identical medical term may have quite another meaning in other areas.

He argues that there has been a breakdown of what systemization there was in traditional Hausa medicine, with an increasing individual personalism, each person now having to maintain a degree of secrecy about his or her own problems and solutions, and a skeptical attitude is predominant in dealing with any treatment or diagnosis; a transient popularity for new cures appears among entrepreneurs whose eventual fall from grace is met with fresh skepticism. Last suggests that this non-systematization is perhaps temporary: with both Islamicization and Westernization, more systematic practices will emerge. What is not clear is whether nonsystematization will prove to be a historical phenomenon in this particular context, or whether it is perhaps some aspect of local medicines in general. Elsewhere Last suggests the latter.