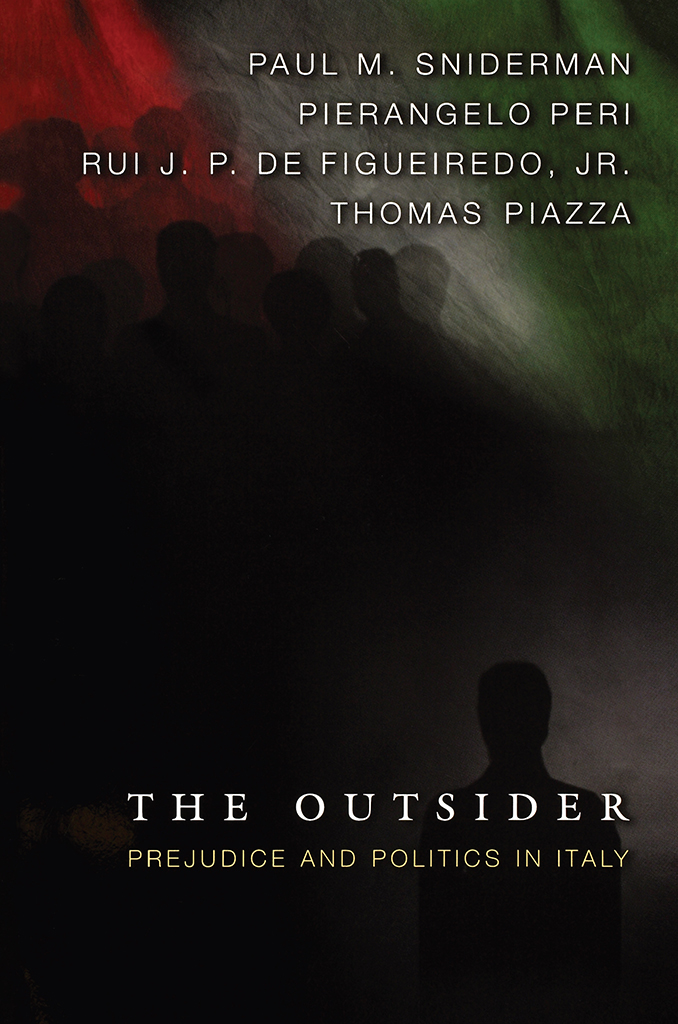

Paul M. Sniderman - The Outsider: Prejudice and Politics in Italy

Here you can read online Paul M. Sniderman - The Outsider: Prejudice and Politics in Italy full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Outsider: Prejudice and Politics in Italy

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Outsider: Prejudice and Politics in Italy: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Outsider: Prejudice and Politics in Italy" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

One of the most wide-ranging studies of prejudice undertaken in a decade, The Outsider combines new research methods and rich analysis to upend many of our assumptions about prejudice. Noting that hostility toward immigrants has been on the rise throughout Western Europe, Paul Sniderman and his team conduct the first study of prejudice in Italy and offer insights applicable to nearly all countries worldwide. The study of prejudice, they argue, has been both stimulated and limited by tensions among partial theories. Prejudice and group conflict are said to be rooted in the psychological makeup of individuals, or alternatively, to spring from real competition over material goods or social status, or yet again, to follow in the wake of a quest for identity. It is the distinctive effort of The Outsider to develop a unified theory of prejudice integrating personality, realistic conflict, and social identity approaches.

Drawing on computer-assisted interviewing, this book focuses on Italy partly because it has experienced two different waves of immigration, from Northern Africa and Eastern Europe, and thus allows one to consider to what extent the color of immigrants skin imposes a special burden of prejudice. Italy is also an apt site for the study of intolerance because of long-standing prejudices that have existed internally, between Northern and Southern Italians. The books findings show that any point of difference--color, nationality, or language--marks the immigrant as an outsider. The fact of difference, not the particular mode of difference, is crucial. Moreover, the general election of 1994 provided a rare opportunity to investigate the political impact of prejudice when the party system was itself in the process of transformation. The authors uncover a potential line of cleavage: rather than prejudice being concentrated on the political right, it has a wide following among the less educated of the political left.

Analyzing the contributions of personality, social-structural factors, and political orientation to the wave of intolerance toward immigrants, The Outsider offers unprecedented insights into the phenomenon of prejudice and its link to politics.

Paul M. Sniderman: author's other books

Who wrote The Outsider: Prejudice and Politics in Italy? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.