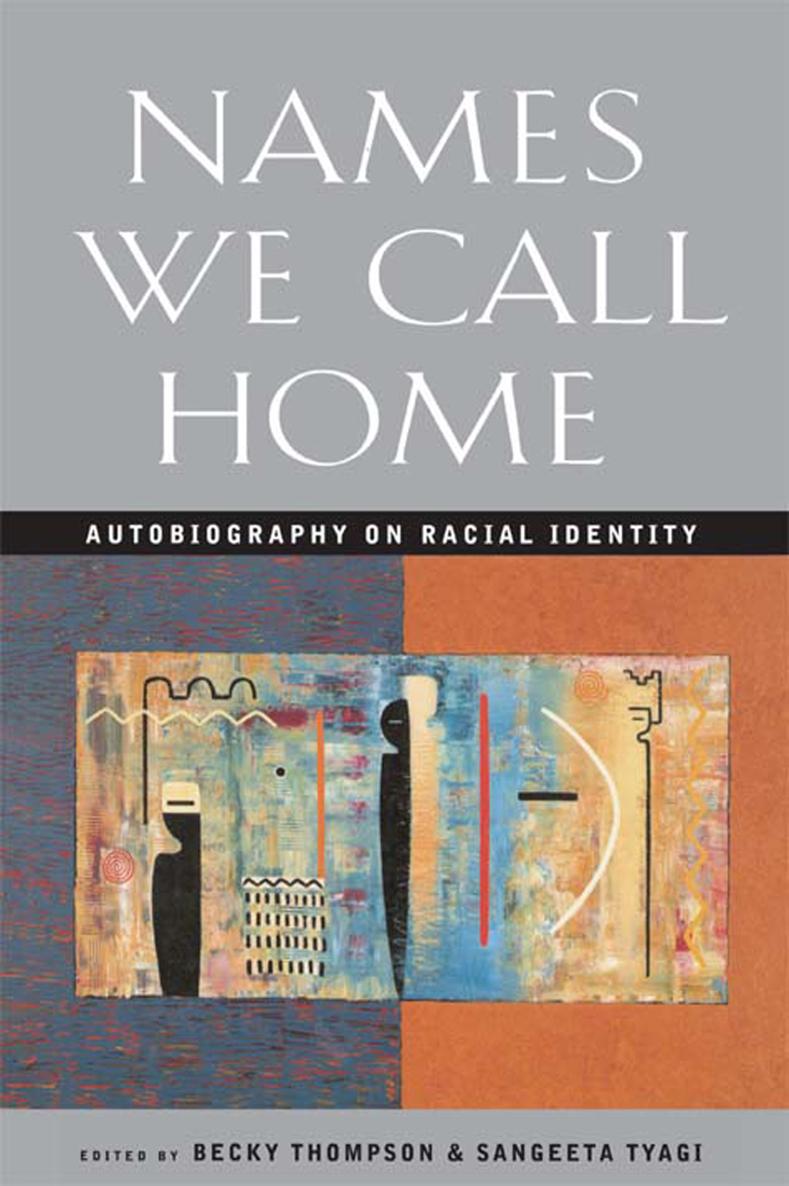

Names We Call Home

Names We Call Home:

AUTOBIOGRAPHY ON RACIAL IDENTITY

EDITED BY BECKY THOMPSON AND SANGEETA TYAGI

Published in 1996 by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park

Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Copyright 1996 by Routledge, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Angela Davis's essay first appeared in the anthology Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography (New York: The New Press, 1994), edited by Deborah Willie. June Jordan's essay was adapted from Beyond Gender, Race, and Class, a speech delivered by the author at the Eighth Annual Gender Studies Symposium, Visions and Voices for Change, at Lewis and Clark College, Portland, Oregon, in April 1989. It was published in The Progressive, June 1989 and in June Jordan, 1992. Technical Difficulties: African-American Notes on the State of the Union. New York: Pantheon. pp. 161-68. Cherre Moraga's essay originally appeared in The Last Generation by Cherre Moraga (Boston: South End Press, 1993), and is reprinted here courtesy of the author and publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names we call home : autobiography on racial identity / edited by

Becky Thompson and Sangeeta Tyagi.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-415-91161-3 (hb). ISBN 0-415-91162-1 (pbk.)

1. EthnicityUnited States. 2. Group identity United States.

3. United StatesRace relations. I. Thompson, Becky W.

II. Tyagi, Sangeeta.

E184.A1N285 1995

305.8' 00973dc20

Contents

Acknowledgments

At a time in United States racial history that threatens to repeat the nadir at the turn of the 20th century, this book is meant as a political salvo, a psychic antidote, and a communal laying on of hands, as the authors seek to claim racial identities that are not based on conquest or defacement. As this book goes to press, we give thanks first and foremost to the authors whose stories have dazzled and sustained us. As the activist writer Margaret Randall aptly notes, as happens with all authentic projects, the material uncovered dictates the book to be written. For the authors' unearthing of rich stories and fertile political thought, we are grateful. Although Names We Call Home is technically an edited volume, the authors' generosity throughout makes collaboration a more accurate term.

We are especially grateful to Gloria Anzalda whose writing on mestiza consciousness inspired the idea for this volume. Thanks as well to Becky's grandparents, Beth and Jim Fillmore, whose knowledge of Hopi and Navajo art led us to Dan Namingha's brilliant artistry and the painting that graces the cover of this book. We have also received able and creative support from the editors and production coordinators at Routledge, Jayne Fargnoli, Anne Sanow, and Kimberly Herald, and invaluable guidance from Sally and Edward Abood, Elly Bulkin, Atreya Chakraborty, Peter Erickson, Ruth Frankenberg, Lisa Freeman, Susan Kosoff, Gayle Pemberton, and Niko Pfund. We are grateful to Earl Jackson and Lisa Hall who gave of themselves in extraordinary ways throughout this project. We also give thanks to Vanetta Aaron, Duncan Thomas, Dave and Bill Wangsgaard, and Irving Zolawho have passed on during the time the editors and contributors worked on this volume, but whose spirits remain close to us. Finally, we give thanks for having the chance to work together again as editors. In Sisters of the Yam, bell hooks writes, work makes life sweet. We agree, and would add to this adage: Working together makes life sweet.

Margaret Randall. 1994. Sandino's Daughters Revisited: Feminism in Nicaragua. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers, p. xiii.

bell hooks. 1993. Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery. Boston, MA: South End Press, p. 41.

Introduction

Storytelling as Social Conscience

The Power of Autobiography

Becky Thompson and Sangeeta Tyagi

T rying to understand race in the United States is like putting together a three-dimensional 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle in dim light. Given the vicissitudes of historical amnesia and the elusive quality of communal memory, it is unclear if we even have all the pieces to begin with. Race is about everythinghistorical, political, personaland race is about nothinga construct, an invention that has changed dramatically over time and historical circumstance. From the smallest of gestureswhat is packed in a child's lunch box or passed on in a smile or a frownto the largest of historical statementsBrown vs. Board of Education, the Vietnam War, the Hyde Amendmentrace has been, and continues to be, encoded in all of our lives. And yet, the fact that race operates on so many different levels is partly what makes talking about peoples' racial identities so difficult. This paradox, when coupled with race's plasticity when gender, sexuality, nationality, age, and religion are accounted for, makes for a conundruma puzzle admitting no easy or singular solution. This anthology offers courageous and innovative assessments of this conundrum, with twenty-seven appraisals of the everyday details and historical events that continue to inform and transform people's racial identifications.

The decision to call together these contributors for this joint project was born out of our interest in how progressive writers and activists in the 1990s carve out the creative spaces we need to maintain antiracist stances in our work and lives. As friends and intellectual partners for many years, we have grappled with, argued about, and marveled over how often weas a heterosexual woman raised middle class and Hindu in India and as a white, mixed-class lesbian of Mormon extraction who grew up in the United Statesexperience the world similarly and differently in the same breath.

The very different ways we have needed to negotiate in the world have figured prominently in our vision for the anthology. The most pivotal component of Sangeeta's racial identity in the United States has centered on her experiences as an immigrant woman and the racialized process of getting a green card. For Sangeeta, what home has meant has been inextricably linked to a politics of exclusion based on race and nationality. While Sangeeta has fought to establish her right to a home in the States, Becky has been working to create a safe one in a country where that is rarely guaranteed for womenacross lines of race, class and sexuality. As we have been trying to create safe space amid very different threats to such security, we have been home to each otheras friends, intellectual partners, and political allies. These realitiesand our discussions about themhave underscored our desire to know more about people whose multidimensional struggles and identities have required new names and the creation of new homes.