2012 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of

the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State College, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State College of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State College of Colorado.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Neoliberalism and commodity production in Mexico / Thomas Weaver ... [et al.].

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60732-171-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-60732-172-9 (ebook)

1. MexicoEconomic policy21st century. 2. NeoliberalismMexico. 3. Commercial

productsMexico. 4. MexicoForeign economic relations. 5. MexicoSocial conditions21st

century. 6. Working classSocial conditionsHistory. I. Weaver, Thomas.

HC135.N414 2012

338.0972dc23

2012010192

Design by Daniel Pratt

21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

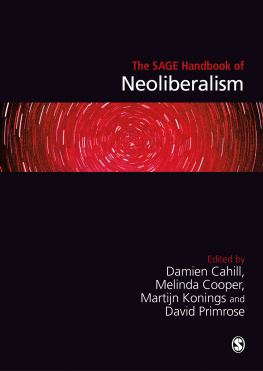

Preface

There are natural disasters, and then there is neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is an economic philosophy that holds that free markets provide the most efficient solution to economic and social problems and that governments should not interfere with them. Its adherents advocate removing protectionist barriers to free trade, as well as encouraging privatization and foreign investment. Consistent with these principles, neoliberals also advocate deregulation, unfettering capital by reducing taxes, downsizing government, and reducing spending on social programs. Under President Ronald Reagan of the United States and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Great Britain, neoliberal economic fundamentalism gained ascendancy and informed the economic policies not just of those countries and their allies, but it also came to guide World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) lending. With the Mexican crisis in 1982 (which required a bailout of US banks as well), Mexico became the test case for World Bank and IMF neoliberal policies of structural adjustment.

This book takes an anthropological approach to Mexicos experience with neoliberalism by examining its effects on the production and distribution of some basic commodities. Mexico is a particularly interesting country in which to examine neoliberalism, for several reasons. First, the current neoliberal reforms are not Mexicos first experiment with such policies. Its nineteenth-century foray into liberal reforms, which concentrated wealth into the hands of a few, produced such poverty and misery among peasants and workers that it gave rise to the Mexican Revolution (19101920). In the wake of the revolution, Mexico adopted social policies aimed at protecting the interests of peasants and workerswhich included the nationalization of land, waters, and mineral rightsand enacted policies that sought to foster industrialization by protecting national industries from foreign competition. Second, because the current enactment of neoliberal policies represents a profound abandonment of the policies enshrined by the Mexican Revolution, this history and dramatic turnaround make Mexico an engaging context within which to examine neoliberalism. Finally, the IMF and the World Bank have applied many of the neoliberal policies and measures first tried in Mexico across the developing world. We believe that Mexicos experience with neoliberalism holds important lessons not only for developing nations but for developed ones as well. Mexico offers an object lesson in the consequences these policies may have if applied at home or when they come home to roost.

The neoliberal transformation of Mexico has been profound. The Mexican state has been forced to open its markets, abandon its social programs, and privatize most state-run industries and ejido lands. Under Mexican law an ejido refers to lands given to a community or group of people through the process of agrarian reform. While this process has produced winners, it has also been costly. Rural smallholders have been among the losers generally, as the Zapatista uprisings, subsequent rebellions, and troubles attest. While smallholders were offered individual titles to the parcels they worked on state-administered ejido lands, neoliberal policies also eliminated the subsidies and credit that made smallholders productive. Facing increasingly precarious livelihoods, many left the countryside to search for work in burgeoning cities or in el Norte. The number of undocumented workers increased from around 2 million in 1980 to about 12 million in 2008 (Chapa 2008; Passel and Cohn 2008). While the US economy has benefited most from this cheap labor, migrant worker remittances have become Mexicos second-largest source of foreign revenue, after crude oil (Banco de Mxico 2007), increasing from $3.6 billion in 1990 to $23.8 billion in 2008 (Ratha, Mohapatra, and Xu 2008; Sana 2004).

Although rural Mexico is the main focus of this book, neoliberal policies have also had profound impacts on Mexicos urban and middle classes. Free trade and privatization policies have decimated domestic industries or pushed them into different sectors and locations altogether. Neoliberal policies aimed at downsizing government, cutting jobs and social programs, and eliminating or reducing subsidies for basic consumer goods have led to a long-term decline of real purchasing power that has deeply affected those classes as well.

The disaster in rural Mexico goes beyond the loss of its workers or the dependence on remittances and welfare or even the loss of lands. The decimation of smallholder livelihoods has also opened a space for drug production, which, given US demand, has spurred a vast increase in their illicit cultivation. Available figures suggest that marijuana production in Mexico has tripled since 1990. Heroin and cocaine production has also surged. Two notable neoliberal achievements are relevant in this regard. In the late 1980s the quota agreements that for decades had regulated coffee production were not renewed. Under NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement), tariffs on corn were eliminated, effectively flooding the Mexican market with cheap US corn. With the fall of coffee and corn prices and limited government assistance to farmers, poppy farming, Bucardo notes, has exploded in the southwestern Mexican state of Guerrero in the past decades as coffee and corn prices have fallen and government assistance has been drastically reduced. Now opium gum sells for seven to twelve dollars per pound in contrast to a fifteen cents a pound price for coffee (Bucardo et al. 2005:284). Expanding drug production and trafficking breeds violence and corruption and now threatens the Mexican government and is threatening to spill across the border as well. The flow of Mexican migrant workers and drugs to the United States is not simply a response to US markets and demands; it is abundantly clear that, in pushing Mexico to adopt neoliberal policies, the United States helped create the underlying conditions responsible for these flows.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).