Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weil, Joyce.

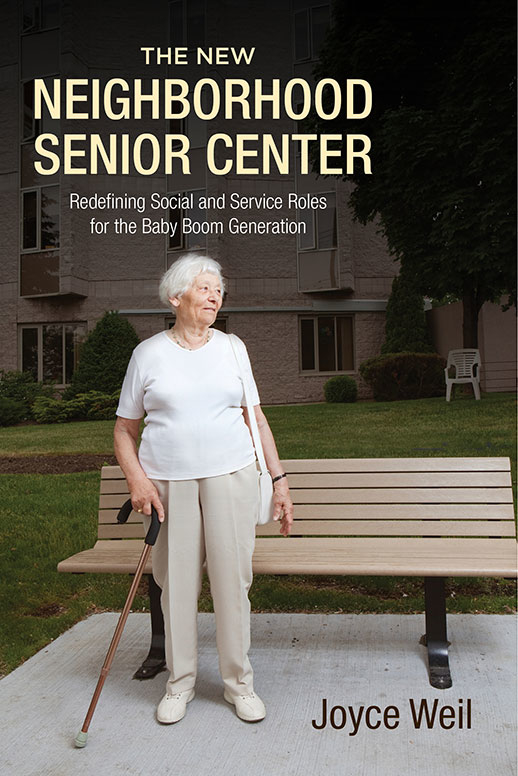

The new neighborhood senior center : redefining social and service roles for the baby boom generation / Joyce Weil.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780813562957 (hardback) ISBN 9780813562940 (pbk.) ISBN 9780813562964 (e-book)

1. Senior centersNew York (State) 2. Senior centersUnited States. 3. Baby boom generationService forNew York (State) 4. Baby boom generationService forUnited States. 5. Older peopleServices forNew York (State) 6. Older peopleServices forUnited States. I. Title.

HV1455.2.U62N78 2014

362.6'309747dc23 2014004943

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2014 by Joyce Weil

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

Visit our website: http://rutgerspress.rutgers.edu

Manufactured in the United States of America

As I write this preface in March 2014, after the body of the book has been written, senior centers remain in the midst of great change. The reauthorization of the Older Americans Act (OAA), delayed over 20112013, has not yet happened but appears to be gaining renewed momentum. Senior nutrition program fundinga mainstay of centersremains dependent on states funding reserves yet has had to endure a recent political impasse that briefly shut down the federal government. Still, despite delays and cuts, the OAA holds great promise to expand the group of older persons reached by centers. Also, centers can now modernizewhatever that may come to mean.

I did not begin to study a senior center to talk about metapolicy changes. This work started in 2008 as a simple summer project; I wanted to examine how senior centers might affect older persons lives. I hoped to interview center participants and see how a group of elders in Queens, New York, viewed their senior citizens center (as they were still called at the time). What some may think of as a quaint setting with bingo playing and little old ladies eating a group meal was definitely not the case. Yes, I cannot lie, there was bingo, and congregate meals were served, but a fuller picture of the world of the center truly opened up to me. It became so much larger than the four walls with the check-in and sign-in sheets, meal tickets, and holiday parties. As the center, like many others in New York City, began to close, or be shuttered, as this process is often described, a new world of politics and infrastructure with players and agents presented itself to me. I became an observer of a larger process, and the scope of my ethnography expanded.

This book gave me the space to explore, from many vantage points, facets of what a senior center is and where centers currently sit in our society. I wanted to understand how projections about the (almost mythological) baby boomers were affecting the real, lived situation of persons sixty-five and older. I desired to explore how the setting of New York City and social class were also actors on the stage of the decision-making process about centers futures.

As I wrote the final chapter, the citys innovative center models were in their fledgling stages. Vermont senator Bernie Sanderss 20112013 reauthorization of the Older Americans Act was under way, but with much debate, sequestration, and the federal shutdown, it was delayed. This reauthorization has the power to expand the population targeted by centers, while the modernization component will, hopefully, set more research and evidence-based plans in motion.

I wanted to learn what happens when working-class elders lose a center (a sense of space and a familiar social and service-provision setting) and where the displaced center members would go. How did all the piecesthe center participants, staff, community members, Department for the Aging (DFTA)come together? I was intrigued to learn how and why all efforts to keep the center from closing failed in the end. What social capital and which social ties worked? What social capital and which ties were missing? And were other underlying events and processes at work?

During these past three years, I have felt as though I was at the precipice of the imminent changes in the senior center movement and kept thinking, Are these proposed changes more than semantic ones? Will baby boomers really differ? What image of a boomer are we planning for? Do existing centers really need to be fixed? Why are we constructing currently old centergoers and seeing their needs as different from, or even less than, those of baby boomers? Would new center models be a momentous improvement?

This book travels down many paths to reconstruct the life and closure of one center as a case to open up a window and broaden the scope in order to investigate these larger issues.

For me as a native New Yorker, born and raised in Queens, and a sociologist and gerontologist, it was very meaningful to combine all my roles and interests in the process of writing this book. By exploring this shuttering issue on many levels (individual through policy), I truly realized that there were no easy villains; large-scale change is a complicated process. I gained perspective as an author.

Handling an ethnographic case study, providing pseudonyms to elder participants, moving into policy issues, and interviewing and obtaining consent from experts took time and tact. So did protecting the identity of the center while describing its participants in detail. In some chapters, I walked the line of using press accounts without identifying the community. Getting access to multiple field settings and a main site, the center, through many staff changes, taught me patience and persistence, especially whenunknown to me at the timelarger changes were in the offing.

The entire work for this book spans 20082013, six years of data collecting and analysis. Being embedded in this center during parts of the closure process and being able to widen the focus to policy makes this book unique in its approach to center closure and modernization. I was also fortunate to talk to many key figures in the aging network in New York City and add their observations to my own. I used local media coverage of the center closures and innovative centers, as well, including the closure list, released internally at a City Council meeting and leaked in a newspaper blog. And I included evidence of larger policies, such as the Older Americans Act and the Affordable Care Act, since their changes directly relate to senior centers functions.

I would like readers to be aware of the structure of the book, specifically the changing scope of the chapters. The general format here is that chapters begin with an ethnographic or narrower focus on the center, the people connected with it and its neighborhood, then move on to address issues on a larger scale, bringing in social policy. After giving an overview of the neighborhood and senior center in the Introduction, I set the stage in chapter 1 for the centers role and theories of why senior centers work. Chapters 2 and 4 are ethnographic and focus at the level of the center, the extended case study for the book. Chapter 3 moves the scale up to include city, state, and national debates about what senior centers should be, who should fund them, and whom they should serve. Then chapters 5 and 6 apply multidisciplinary theories to the events described in prior chapters. Chapter 7 looks at the local and national trends of changing centers to meet baby boomers turning sixty-five years of age. Chapter 8 concludes on the largest level, analyzing federal policies and giving suggestions for center sustainability in the nation as a whole.