BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY PRESS

1999 Brandeis University Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Michael P. Burton

Typeset in Janson and Castellar by Generic Compositors

For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Brandeis University Press, 415 South Street, Waltham MA 02453, or visit brandeis.edu/press

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-68458-059-0

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Cohen, Naomi Wiener

Jacob H. Schiff : a study in American Jewish leadership / by Naomi

W. Cohen.

p. cm. (Brandeis series in American Jewish history, culture, and life)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87451-948-9 (cl. : alk. paper)

1. Schiff, Jacob H. (Jacob Henry), 1847-1920. 2. JewsUnited States Biography. 3. Jewish capitalists and financiersUnited StatesBiography. 4. PhilanthropistsUnited States Biography. 5. JewsUnited StatesPolitics and government. 6. United States Biography. I. Title. II. Series.

E184.37.S37C64 1999

332'.092dc21

[B]

9930392

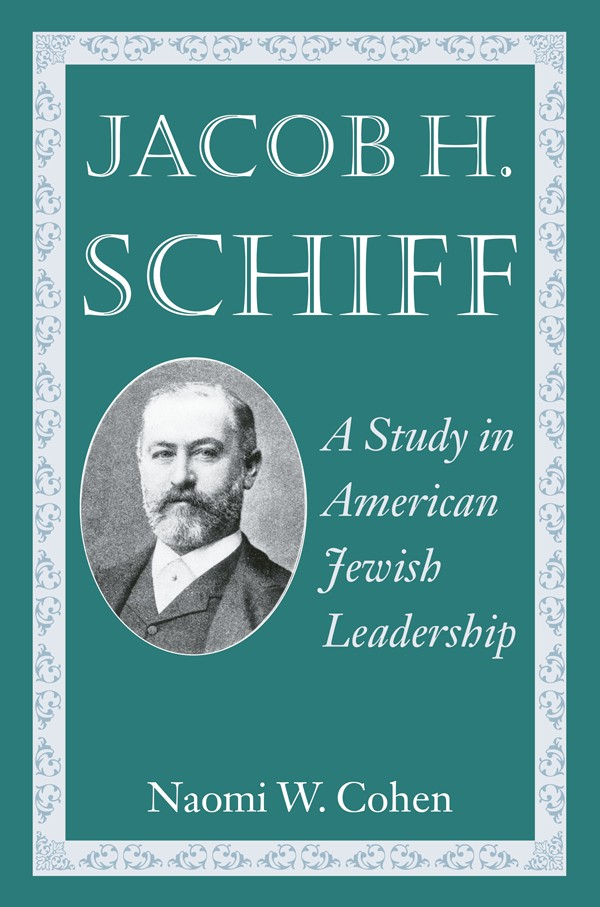

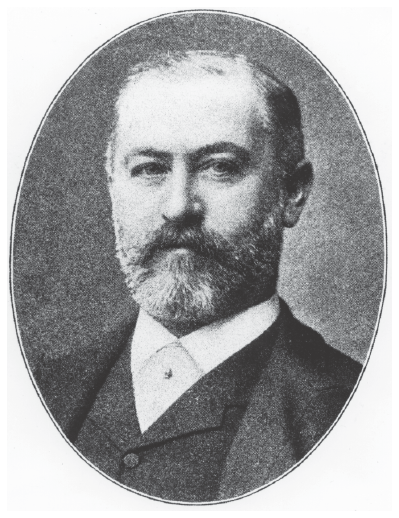

FRONTISPIECE

Image of Jacob Henry Schiff.

American Jewish Historical Society,

Waltham, Massachusetts, and New York, New York.

Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life

JONATHAN D. SARNA, Editor

SYLVIA BARACK FISHMAN, Associate Editor

Leon A. Jick, 1992

The Americanization of the Synagogue, 18201870

Sylvia Barack Fishman, editor, 1992

Follow My Footprints: Changing Images of Women in American Jewish Fiction

Gerald Tulchinsky, 1993

Taking Root: The Origins of the Canadian Jewish Community

Shalom Goldman, editor, 1993

Hebrew and the Bible in America: The First Two Centuries

Marshall Sklare, 1993

Observing Americas Jews

Reena Sigman Friedman, 1994

These Are Our Children: Jewish Orphanages in the United States, 18801925

Alan Silverstein, 1994

Alternatives to Assimilation: The Response of Reform Judaism to American Culture, 18401930

Jack Wertheimer, editor, 1995

The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed

Sylvia Barack Fishman, 1995

A Breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community

Diane Matza, editor, 1996

Sephardic-American Voices: Two Hundred Years of a Literary Legacy

Joyce Antler, editor, 1997

Talking Back: Images of Jewish Women in American Popular Culture

Jack Wertheimer, 1997

A People Divided: Judaism in Contemporary America

Beth S. Wenger and Jeffrey Shandler, editors, 1998

Encounters with the Holy Land: Place, Past and Future in American Jewish Culture

David Kaufman, 1998

Shul with a Pool: The Synagogue-Center in American Jewish History

Roberta Rosenberg Farber and Chaim I. Waxman, 1999

Jews in America: A Contemporary Reader

Murray Friedman and Albert D. Chernin, 1999

A Second Exodus: The American Movement to Free Soviet Jews

Stephen J. Whitfield, 1999

In Search of American Jewish Culture

Naomi W. Cohen, 1999

Jacob H. Schiff: A Study in American Jewish Leadership

Barbara Kessel, 2000

Suddenly Jewish: Jews Raised as Gentiles Discover Their Jewish Roots

Jonathan N. Barron and Eric Murphy Selinger, editors, 2000

Jewish American Poetry: Poems, Commentary, and Reflections

Preface

At a conference of the American Academy for Jewish Research some twenty years ago, I delivered a paper on the reaction of American Jewry to anti-Semitism in Bismarcks Germany. During the question period, the elderly widow of an illustrious Jewish scholar, who had grown up in fin-desicle Germany, posed a three-word query. Unconcerned with my learned explanations she asked in a thick accent: Vere vas Schiff? She, a younger contemporary of Schiffs, well remembered that in times of crisis American Jews looked first to Jacob Schiff (18471920), the head of the powerful banking firm of Kuhn, Loeb & Company, for an appropriate response.

Succeeding generations rapidly forgot. Today, for example, virtually no one can locate the street on New Yorks Lower East Side that was named Schiff Parkway after the bankers death. Modern scholars too showed little interest in the man. In 1988 the editors of the journal American Jewish History conducted a survey of American Jewish historians to ascertain their choices for the two greatest American Jewish leaders, one of the nineteenth and one of the twentieth century. Roughly of the same age as the bankers great-grandchildren, not one of the respondents voted for Schiff. Even they, experts in the historical development of American Jews, ignored the man so important to Jews of his era.

That Schiff was forgotten or ignored in no way diminishes his significance or the significance of his achievements. Indeed, the wide range of his activities is so impressive that it alone may have daunted would-be biographers. This study, which aims in part to rescue Schiff from undeserved oblivion, makes no claim to all-inclusiveness. Its prime focus is on the public Schiff, the way in which he became and behaved as the foremost American Jewish leader of his day. Since American Jewish institutions have become increasingly alert to problems of communal leadership, an analysis of Schiffs objectives and methods can be of more than historical interest.

There is no fixed, satisfactory model against which one can measure what makes an American Jewish leader and what accounts for his success. Various interpretations have been offered, each recognizing a different configuration of factors like personality, ancestral traditions of the group, and the needs of the minority in relation to the demands of the larger society. None, however, readily fits Schiff. His leadership, suggestive in style of the contemporary individualistic captains of industry, differed qualitatively from that of his Jewish predecessors, contemporaries, and successors. His wealth and his status in the America of 18751920 set him apart, but equally distinctive was his voluntary involvement nationally and internationally in the totality of Jewish interests.

An understanding of Schiffs leadership must also factor in other considerations. For example, how was he rated as a leader by those he led? How successful was he in arousing an awareness of Jewish interests on the part of the Jewish community, the government, and American society in general? To what extent did emotional and psychological nuances of his approachon the one side, a pride in Judaism and its cultural heritage, a genuine compassion for the needy, a hypersensitivity to the Jewish image, and a vision of a secure and united American Jewish community; and on the other, a hot temper and arrogant demeanorgovern his public behavior? Did his failures, and indeed many of his ideas did not bring about desired results, compromise his leadership?

Issues that engaged Schiff sprang from the condition of the Jewish community as he perceived it, both in the United States and in Europe, and from problems that arose when the minority group appeared out of step with American society. A constant concern, whether by itself or in tandem with a larger question, was discrimination against Jews. Although Schiffs behavior was reactive to such stimuli, the solutions he proposed were often innovative. Their application reflected the assets of wealth, a broad network of well-placed friends and acquaintances, and the executive talents he had skillfully honed in the business world. Rigidity on basic values notwithstanding, he was able to compromise on specific issues and then justify the compromise for the sake of his larger communal agenda. Where necessary he sought the advice of associates and friends on strategy; on many occasions he acted independently. Overall, he had the ability to interpret long-range economic and social trends, and the answers he came up with were often indicators of the rapid changes taking place in both the American and the Jewish communities.