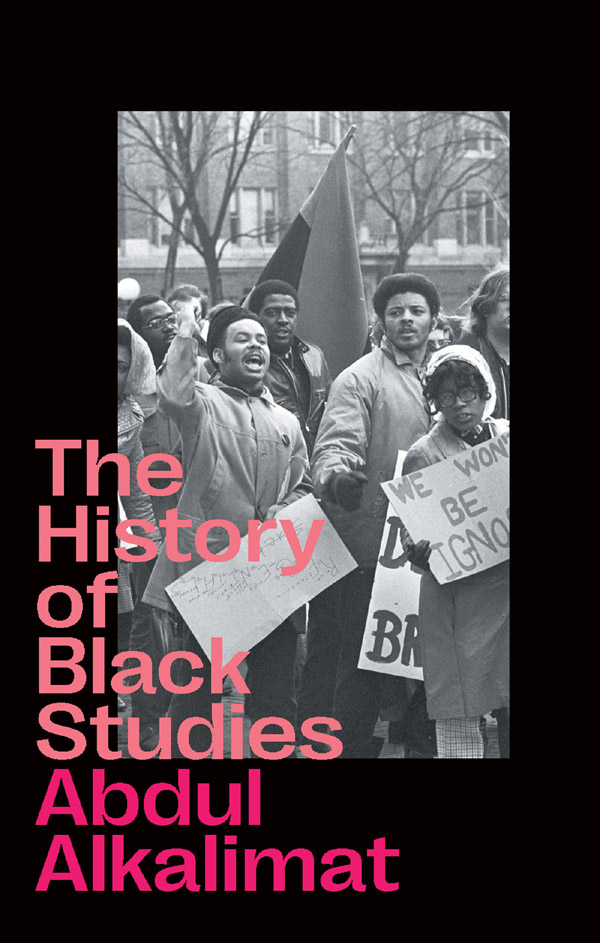

The History of Black Studies

Abdul Alkalimat is one of the most rigorous and committed Black radical thinkers of our time.

Barbara Ransby, award-winning author of Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement

Magisterial [...] The most comprehensive history of the field of Black Studies. This landmark book will become a standard in the history of our field.

Professor Molefi Kete Asante, Department of Africology, Temple University

Abdul Alkalimat, one of the pioneers of Black Studies, has done a great service by providing a powerful, expansive, and compelling history of the field.

Keisha N. Blain, award-winning author and co-editor of the #1 New York Times Bestseller Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America 16192019

This is Alkalimats magnum opus [] a focal point for scholarship on the history of Africana thought in the academy. It is required reading for Black Studies scholars and intellectual historians.

Fabio Rojas, Virginia L. Roberts Professor of Sociology, Indiana University

A visionary and a documentarian, Alkalimat has been a major figure in the Black Studies movement since its modern inception. This landmark book is indispensable.

Martha Biondi, author of The Black Revolution on Campus

First published 2021 by Pluto Press

New Wing, Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 1LA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright Abdul Alkalimat 2021

The right of Abdul Alkalimat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 4423 2 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 4422 5 Paperback

ISBN 978 0 7453 4426 3 PDF

ISBN 978 0 7453 4424 9 EPUB

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America

To my comrades in Peoples College

and the Black student activists of todayIntroduction

This book tells the history of Black Studies, familiar to many as the campus units that teach college-level courses about African-American history and culture. This book will present a comprehensive survey of all such programs, but Black Studies has been more than that.

The term Black Studies emerged in the 1960s but, as this book will demonstrate, Black Studies developed over the entire course of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century. This book defines Black Studies as those activities:

(1) that study and teach about African Americans and often Africans and other African-descended people;

(2) where Black people themselves are the main agents, or protagonists, of the study and learning;

(3) that counter racism and contribute to human liberation;

(4) that celebrate the Black experience; and

(5) that see it as one precious case among many in the universality of the human condition.

Each of these five points will be considered further along in this introduction.

Now is an appropriate time to write and read a history of Black Studies because colleges and universities across the USA have been celebrating the fiftieth anniversaries of the founding of their Black Studies programs. Campuses are bringing together the alumni, faculty, and community activists who helped found their respective programs. Each has its own particularity but, to draw larger conclusions, we need to consider frameworks that can be used to compare and talk about all these local histories.

This is also a moment when the generation who founded Black Studies at mainstream colleges and universities is moving into retirement and facing health challenges and mortality. This brings with it a crisis of both individual and institutional memory loss, a crisis that calls for activities to capture local accounts of the founding and development of Black Studies on each campus.

Finally, Black Studies faces threats. The economic downturns of 2008 and 2020, the latter due to the coronavirus pandemic, have put pressure on higher education. Before then, endowments and public funding kept higher education relatively insulated from economic pressure. But for more than a decade, tuition increases and limits to financial support have impacted Black enrollment as well as support for Black programs.

The resurgence of racism contributes to this daunting atmosphere, both as a broad social reaction and at the highest levels of political leadership. All in all, the most fundamental negative obstacle facing Black people all over the world at this moment hinges on the concept of race.

Science has discredited race as a concept (American Anthropological Association 1998; important studies include Gould 1996; Lewontin, Rose, and Kamin 1984; Prewitt 2013). It is a term that posits a biological and hierarchical classification of humans, Homo sapiens. On this concept rests the practice of racism: large and small prejudicial beliefs, words, and actions that are systematized, institutionalized, persistent, and more or less violent. A liberal justification for the use of the concept of race argues that race is socially constructed. But this falls woefully short. Race is nothing less than a socially constructed lie.

Race serves as a good example of Alfred North Whiteheads fallacy of misplaced concreteness: an abstract idea that does not fit reality (Whitehead 1985 [1925]). Racism exists, but races do not. But as the sociologist W.I. Thomas observes, If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences (Thomas Theorem 2018). Racism infects virtually all areas of scholarship and public policy. Black people are systematically lied about as a justification for their continued exploitation and marginalization in American society.

Racism can be understood as some combination of three false ideas: deficit, difference, and dependency. The deficit idea centers on denying that Black people can reason and think just as well as anyone else. The concept of human reason itself has even been claimed by Eurocentric thinkers as originating in Greece and Rome (see Blaut 1993). Of course, this is self-serving. It also contradicts what we know about the mind and the brain. Any human brain has the same structures or centers that mobilize both thinking and feeling.

The idea of deficit has long taken the form of attacking the capacity of Black peoples brains. One early effort involved classifying head size and shape. It defined the cephalic index as the ratio of the maximum width of the head of an organism (human or animal) multiplied by 100 divided by its maximum length (i.e., in the horizontal plane, or front to back) (Boas 1899). Franz Boas, distinguished anthropologist at Columbia University, took his students Zora Neale Hurston and Margaret Mead to Harlem in the 1920s to measure the heads of Black people as part of disproving this theory (Sigerist Circle Bibliography on Race and Medicine n.d.; Helmreich 2004; Boas 1899; Fergus 2003).