First published 2003 by

Routledge

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2003 by Peter Hervik

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hervik, Peter, 1956

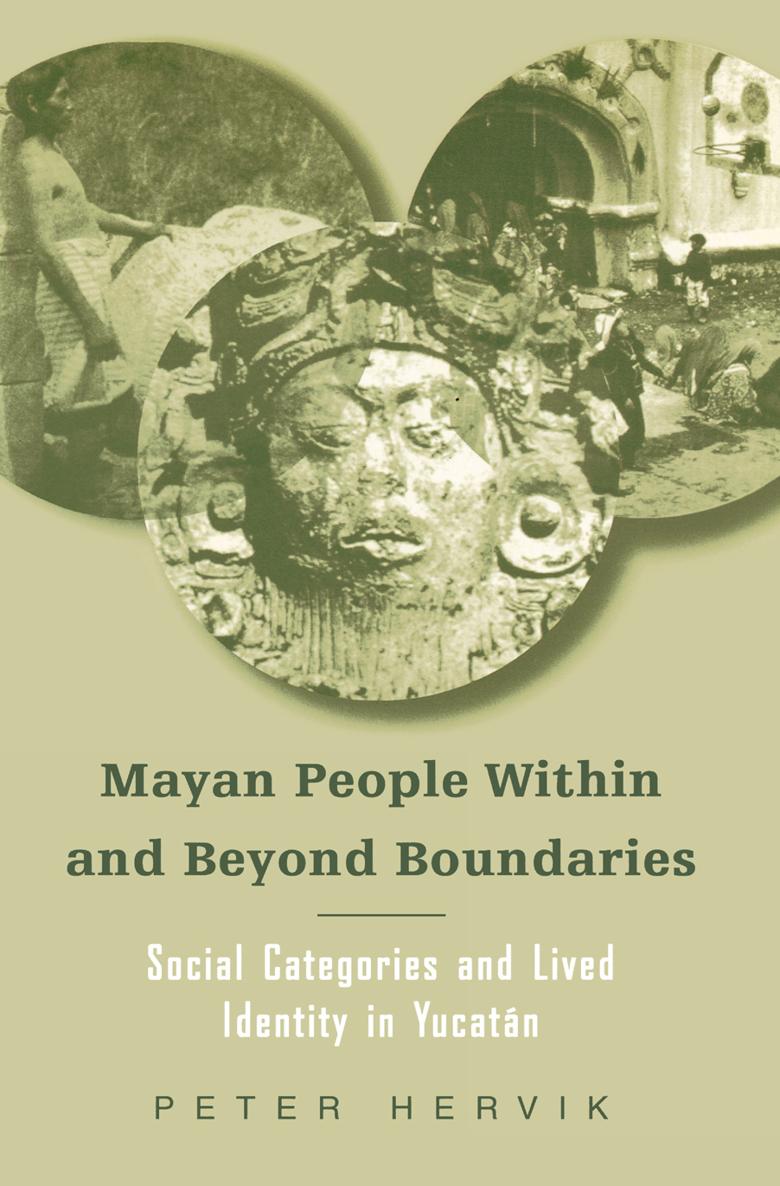

Mayan people within and beyond boundaries : social categories and lived identity in Yucatn / Peter Hervik.

p. cm.

Originally published: Amsterdam : Harwood Academic Publishers, c1999, in series: Studies in anthropology and history.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. MayasMexicoYucatn (State)Social conditions. 2. MayasMexicoYucatn (State)Ethnic identity. 3. Social classesMexicoYucatn (State) 4. Oxkutzcab (Mexico)Social conditions. I. Title.

F1435.3.S68 .H47 2002

305.897415207265dc21

2002035031

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-94526-4 (hbk)

This book is about a native group with a famous past. It challenges previous constructions and representations of the Maya of Yucatn and offers new means for understanding Maya self-identification. The name of an ethnic group is one chief marker of identity, but the name is not always reckoned across boundaries. Social categories of identification make up a lexicon of culture that may not describe living groups of people and how they identify themselves. Anthropologists, folklorists, the National Geographic, and tourist brochures all refer to the people of the Yucatn as Maya when the people themselves think of the Maya as their long dead ancestors and themselves as mestizo. Maya is the name that is meaningful within the field of anthropological studies. Mestizo is a name that is meaningful within the field of local practice. What does it mean for Maya ethnography that the name provides no bridge between the two fields?

Choosing the term Maya rather than mestizo reveals anthropological perspectives and social positions. Different perspectives indexed by the terms generate different interpretations and appropriations that are gained through social interaction. In the case of the term Maya, this interaction does not occur among the Maya people themselves as much as in an external social space where knowledge of the Maya culture is created in academic institutions and by the tourist industry. The categories and identities ascribed to any social group indicate a particular scheme of differential power, status and moral worth positions in a given social field which we as anthropologists have to address. Mayan People Within and Beyond Boundaries is a study of the politics and practices of representing the Maya; its purpose is to identify, critique and overcome the perspectives behind the choice of categories. The study then goes on to discuss the methodological and epistemological implications of the incongruence between external and local naming through a new approach to ethnography referred to as shared social experience.

Recent meticulous attention in anthropology, inspired by postmodernist critiques, to the politics of representation, had led to a sense of crisis in the work of representation and a process where the anthropologist and his or her local informants become more and more salient and self-reflexive in the final texts. Mayan People Within and Beyond Boundaries takes up the issue of naming as an issue of construction and representation in concrete practices in the field and in the text. The book builds upon insights of the postmodernist insistence on decoding the ethnographers use of literary devices to establish authority and legitimizing subjectivity, but goes beyond this point. It offers shared social experience as a more productive means of understanding people and their self-identification.

The interrelationship between academic and local categorization is discussed on the basis of the authors field experiences in Oxkutzcab, Yucatn. Oxkutzcab is the name of a town and a county (municipio) in the very heart of the Yucatn peninsula some 100 km from the state capital of Mrida. The town has 16,000 inhabitants and the county totals 20,000 people. According to the census of the population in 1980, only 30% of those above five years of age were monolingual, equally divided among Maya and Spanish speakers. The majority (70%) of the population is bilingual (INEGI, 1983).

Oxkutzcab has a long-standing reputation of being the garden of Yucatn (huerta del estado) and the home of the famous sweet orange naranja dulce locally known as chinas. Here, Yucatns diversified orchards are found. In 1960, three-quarters of all families made milpas in this fruit- and horticulture zone surrounding the town. By the end of the 1980s, milpa farming was pushed further south.

Oranges are one important cashcrop, despite the fact that the use of oranges in the local diet is severely limited. Many people would drink coke rather than freshly squeezed orange juice. Children do not eat oranges. This is one of the few places that I know of where oranges are first peeled like an apple, cut into halves and sprinkled with chilli before the juice is soaked out.

I arrived in Mrida in September of 1989 with my family to begin fieldwork in Oxkutzcab. I had been there before. During a prior research projectwhere I sought to register all circulating contemporary Maya textsI had visited Oxkutzcab to prepare for field-work. This town dominated by farmers suited me not only because of the easy collaboration with Carlos Armando Dzul Ek, the bilingual teacher and principal of a school in Mani, but also because of the high number of bilingual speakers. Other criteria were the historically large migration, intensive state influence that channelled new resources to the area. I was interested at the time in what impact this economic development had for the social mobility and in particular how that mobility was guarded by political and cultural brokers. In these considerations Dzul Eks outstanding offer of practical support was also of critical importance due to my fieldwork situation.

Fieldwork was a family enterprise that involved my wife, who is trained as a social anthropologist but working in journalism, one son who had just turned three years, and our twin boys, 13 months old.

Some weeks after having arrived in Mrida, the state capital, we headed south in our newly acquired car, necessary for the benefit and welfare of the family. The old Datsun had no seat belts, but quickly our three boys, Daniel, Simon, and Thomas learned to sit or stand in the back seat without falling when the car stopped, accelerated, or turned.