First published 1997 by Westview Press, Inc.

Published 2021 by Routledge

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Franics Group, an informa business

Copyright 1997 by Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dizard, Wilson P.

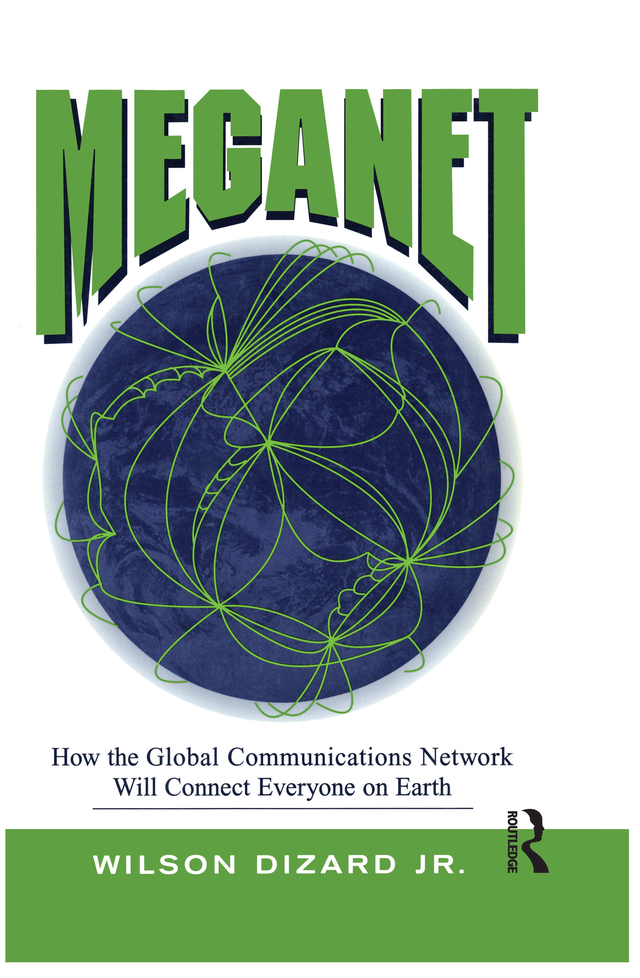

Meganet : the global communications network will connect everyone on earth / Wilson Dizard, Jr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-8133-3017-3 (hc.) ISBN 0-8133-3018-1 (pbk.)

1. Telecommunication. 2. Telecommunication policy. 3. Information superhighway. I. Title.

HEY7631.D59 1997

384dc21

97-13218

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-3670-0967-0 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-3671-5954-2 (pbk)

Within the next generation, almost everyone on earth will be linked on an electronic network. At the simplest level, this means that we will all be able to make a phone call to anyone any place. Today, only one-half of the planet's population can do this.

Meganet explores this prospect and how it is unfolding. It has taken 125 years, beginning with the invention of the telephone, for a global network to come close to being a reality. The reasons for the delay are complex, as we shall see. But the past two decades have witnessed a convergence of forcestechnological, economic, politicalthat are speeding up the process in extraordinary ways. The number of telephones worldwide has doubled during the past twenty years. The number will double again in the next ten years. And in the decade after that, access to telephones and other communications devices plugged into the network will be commonplace in every inhabited place. It will be a defining moment in human history.

My shorthand word for the network is Meganet. It is a clich, a convenient handle for tagging a set of ideas and events. The driving force in Meganet's new expansion has been a series of technological breakthroughs, particularly in semiconductor chips, communications satellites, and fiber-optic cables. They are the tools that assure that an advanced Meganet can be completed in the next few decades. Moreover, they assure that Meganet will provide service beyond what the telecommunications industry calls POTSplain old telephone service. The network will be a multimedia resource supplying television, facsimile, radio, data networking, Internet connections, and other services.

None of this will happen smoothly. Technologies do not create networks. They provide options that have to be matched by political and economic decisions. For all the promise offered by Meganet expansion, there are still powerful voices opposed to the changes now taking place. In contrast, there are enthusiasts who see an advanced global Meganet leading us into a sunny new era of world peace and prosperity. In fact, there is a good case to be made for Meganet's disruptive impacts, particularly in upsetting long-standing political, economic, and cultural patterns.

I draw a linesomewhat shaky at pointsbetween Meganet's long-term effects and what is actually happening now. I project a scenario into the early years of the twenty-first century. This leaves the long-term predictions to the futurists, a fraternity that has a consistent record of calling the wrong shots.

Many individuals have helped me in different ways. A special tribute is due to the late Ithiel de Sola Pool of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who was a friend and professional colleague of mine for many years. The title of his last book on communications, The Technologies of Freedom, summarizes all that this book tries to express. I also thank my colleagues at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and those at Georgetown University. In particular, I want to thank Diana Lady Dougan, chief of the center's international communications studies program, and Peter Krogh, former dean of Georgetown's School of Foreign Service. Both of them gave me the space, time, and other resources to finish this work.

Among others who helped me were Anne Branscomb, Scott Chase, Roger Cochetti, George Codding, Fred Cote, Jan J. van Cuilenberg, Everett Dennis, William Drake, Charles Firestone, Robert Frieden, Gladys Ganley, Linda Garcia, Michael O'Hara Garcia, William Garrison, Henry Geller, Robert Kinzie, Anton Lensen, David Lieve, David Lytel, William McGowan, Tedson Myers, Russell Neuman, Eli Noam, Joseph Pelton, Kenneth Phillips, Michael Potter, Monroe Price, Marek Rusin, Michael Ryan, Rick Schultz, Gregory Staple, Ann Stark, John Vondracek, Ernest Wilson III, and Yvonne Zecca. My sonsJohn, Stephen, Wilson, and Markprovided useful comments.

Finally, I extend a special acknowledgment again to my resident editor and thoughtful critic on works in progress, Lynn Wood Dizard.

Wilson Dizaid Jr.

1

BUILDING THE GLOBAL INFORMATION HIGHWAY

It will be the biggest construction job of all time. It is being built now all over the worldin cities and villages, under the oceans and in outer space. The project will be the largest concentration of high technology ever assembled. Its cost, between now and the time it is completed early in the twenty-first century, will be more than $2 trillion.

It is an advanced global communications network, a telecommunications and information grid that will eventually make every place reachable by telephones, computers, facsimile machines, data banks, and all the other paraphernalia of the information age.

It is the Meganetwork. Meganet.

This book reports on the progress (and setbacks) in expanding Meganet resources to everyone on earth. Meganet is a project of vast contrasts. At one level, it involves linesmen stringing wire through South American jungles to connect with a village's single phone. At another level, it includes Motorola executives riding herd on Iridium, a $4-billion project to link millions of mobile phones between any two places around the globe. Iridium will use sixty-six communications satellites, orbiting the earth hundreds of miles up in space, to transfer the calls.