Crime & Social Organization

Advances in Criminological Theory

Volume 10

Crime & Social Organization

Editors

Elin Waring & David Weisburd

with a foreword by Jeremy Travis

First published 2002 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor and Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2002 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

ISSN: 0894-2366

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0064-0 (hbk)

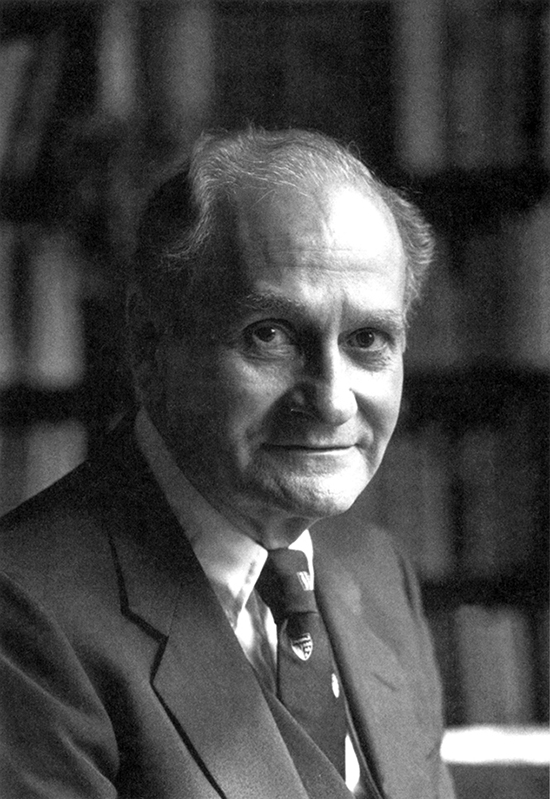

To Albert J. Reiss, Jr.

Contents

Elin Waring and David Weisburd

Diane Vaughan

Joan McCord and Kevin P. Conway

Elin Waring

David F. Greenberg, Robin Tamarelli,and Margaret S. Kelley

Robert J. Sampson

Beat Mohler and Felton Earls

Peter K. Manning

Stephen D. Mastrofski

David Weisburd

Lawrence W. Sherman

EDITORS

Freda Adler

Rutgers University

William S. Laufer

University of Pennsylvania

EDITORIAL BOARD

Kenneth Adams

Sam Houston University

Celesta Albonetti

University of Iowa

James Byrne

University of Lowell

Albert K. Cohen

University of Connecticut

Simon Dinitz

Ohio State University

Delbert Elliott

University of Colorado

Hans Eysenck

University of London

James O. Finckenauer

Rutgers University

Daniel Georges-Abeyie

Florida State University

John J. Gibbs

Indiana University (PA)

Don Gottfredson

Rutgers University

Stepehen D. Gottfredson

Indiana University

Kate Hanrahan

Indiana University (PA)

Patricia Harris

University of Texas

Nicholas Kittrie

American University

Pietro Marongiu

University of California

Joan McCord

Temple University

Joan Petersilia

University of California: Rand Coporation

Marc Riedel

Southern Illinois University

Diana C. Robertson

Emory University

Robin Robinson

George Washington University

Kip Schlegel

Indiana University

Stephen D. Walt

University of Virginia

David Weisburd

Hebrew University

Elmar Weitekamp

University of Tubingen

It is difficult today to imagine a time when criminologists or criminal justice policy makers did not recognize the importance of social organization in understanding crime and the criminal justice system. But this was indeed the case before Albert J. Reiss, Jr. began his pathbreaking work in sociology, criminology, and criminal justice research more than four decades ago. Back then, with few exceptions, criminologists took a unidimensional approach, viewing crime as a series of isolated events, focusing solely on the offender and the offense, with scant attention to the broader social context in which crime is committed. What practitioners might learn from research was accordingly limited. It is no wonder that the response to crime was based on a similar approach, with little thought to the complex web of factors essential to consider in crafting prevention and other crime control strategies.

Today, thanks to Al Reisss pioneering work, policy makers as well as criminologists use this fundamental conceptsocial organizationas a standard analytical tool. What we at the National Institute of Justice refer to as understanding the nexus of crime and other social variables has become a major objective in research and practice. Analyses of the social, organizational, and even the physical environment of crime and the justice system response are now the rule rather than the exception. The same perspective animates policy making and practice. This type of analysis has caused the bar to be raised, with research becoming more complex (and difficult), but with the payoff well worth the effortrichly textured, finely nuanced results, more inspired conclusions.

There is space here to cite only a few of the ways Al Reiss introduced and investigated the study of crime and justice in their social context. He was among the first scholars to plead for shifting the emphasis from studying offenders and their crimes in isolation toward a perspective that includes the networks of relationships binding offenders one to another. What he termed co-offending is a construct that has helped clarify what happens when people act in concert to commit crime. He introduced new ways of thinking about crime control, demonstrating that the way the police go about the job of reducing crime is itself a function of how they are organized and of (ever-changing) external factors. He used a similar organizational focus to alert researchers to why the data they trust so implicitly may not be as reliable and valid as they would like to think. Data are generated by organizations shaped by forces that affect the quality of the information produced. Drawing again on his grounding in sociology, Al gave criminologists a valuable field research tool, systematic social observation, used for the study of policing. More recently, he was a major force in shaping the design of the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, a long-term study of how community, family structure, ethnicity, gender, and a host of other variables influence the origins of criminal behavior. He called the investigators attention to the dynamic nature of communities and of the consequent need to track change over time, and he created a new set of measures for the processes that put people at risk for crime. These and other products of Al Reisss fertile imagination continue to have incalculable heuristic effects.

It is no exaggeration to say that innovations like problem-oriented policing, community-based approaches to crime prevention, the analysis of hot spots, crime mapping, and more recent constructs like collective efficacy, which sees the informal social control mechanisms of neighborhoods as potent forces for preventing crime, have gained currency in large part because of Al Reisss groundwork. A large part of NIJs portfolio is a testament to his influence on criminal justice research.