We both thank Maura Roessner for her support in shepherding this book through to publication as well as her assistance with the book series. We also thank members of the Criminology Explains Advisory Board for their valued input.

CRIMINOLOGY EXPLAINS

Robert A. Brooks and Jeffrey W. Cohen, Editors

This pedagogically oriented series is designed to provide a concise, targeted overview of criminology theories as applied to specific criminal justicerelated subjects. The goal is to bring to life for students the relationships among theory, research, and policy.

Criminology Explains Police Violence, by Philip Matthew Stinson, Sr.

Criminology Explains School Bullying, by Robert A. Brooks and Jeffrey W. Cohen

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2020 by Robert A. Brooks and Jeffrey W. Cohen

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brooks, Robert Andrew, author. | Cohen, Jeffrey W., author.

Title: Criminology explains school bullying / Robert A. Brooks and Jeffrey W. Cohen.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020001535 | ISBN 9780520298262 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520298279 (paperback) | ISBN 9780520970465 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Bullying in schools. | Criminology. | Bullying in schoolsSocial aspects. | School violenceSocial aspects.

Classification: LCC LB 3013.3 . B 766 2020 | DDC 371.5/8dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020001535

Manufactured in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Introduction

We began our research on school bullying in about 2010 when we noticed the disparate coverage of two bullying-related youth suicides in Massachusetts. In the first case, an eleven-year-old African American boy named Carl Walker-Hoover died by suicide on April 6, 2009, in Springfield. In the second case, a fifteen-year-old Irish immigrant girl named Phoebe Prince died by suicide on January 14, 2010, in South Hadley. In both cases, the suicide was linked to bullying victimization. The two suicides occurred less than one year apart and in towns separated by less than twenty miles, and both youths possessed characteristics supporting an ideal victim construction (e.g., young, vulnerable, defenseless, and worthy of sympathy). However, only the Prince case evolved into a signal crime, that is, involving events that, in addition to affecting the immediate participants ... impact in some way upon a wider audience ... caus[ing] them to reconfigure their behaviors or beliefs in some way (Innes 2004, 52). The Prince suicide led to the filing of charges against nine individuals, massive news coverage, and Massachusettss enactment of a new antibullying law. The media gave the Carl Walker-Hoover suicide relatively scant attention. In conference papers and presentations, we explored issues of gender, race, and criminalization around this differing coverage.

We also rapidly expanded our research to include media reports of bullying more generally, which led to the publication of the book Confronting School Bullying: Kids, Culture, and the Making of a Social Problem (Cohen and Brooks 2014). In that book, we explored how the media constructed the phenomenon of school bullying from a relatively minor, localized problem through to its emergence as a major national and international public health concern. We noted that the linking of school bullying to retaliatory violence (e.g., school shootings) and to suicide had by 2013 become a dominant discourse in mainstream news media. Emphasizing such extreme outcomesand linking them together to suggest first a trend and then an epidemicis an important factor contributing to how school bullying came to be perceived as a serious social problem. This contrasts with the early 1990s, when the threat of bullying was usually constructed in rather mild terms. While few dismissed bullying entirely with a kids will be kids attitude, descriptions like the following 1993 excerpt from Lawrence Kutners New York Times Parent and Child column were not uncommon: A 10-year-old who is extorting milk money or threatening to chase a child home after school can loom large in the fears of an 8-year-old. Handing over a quarter a day to avoid possibly being beaten up seems a small price to pay (October 28, 1993, C12). By 2010, bullying had been elevated to a threat of catastrophic proportions; John Quiones opened a segment of NBCs Prime Time Live by asking, Harmless bullying? A simple part of growing up? Or a tragic epidemic that leaves entire schools heartbroken, parents childless and families torn apart? (October 29, 2010).

The confluence of exhaustive media reports, an explosion of academic research, and increased concerns from school systems led to the creation of an antibullying industry marked by consultants, experts, corporate entities, and entertainment celebrities and vehicles. The rise of the antibullying industry helped solidify bullying as a national social problem and also created a risk of cynicism and burnout (Cohen and Brooks 2014).

ACADEMIC INTEREST IN SCHOOL BULLYING

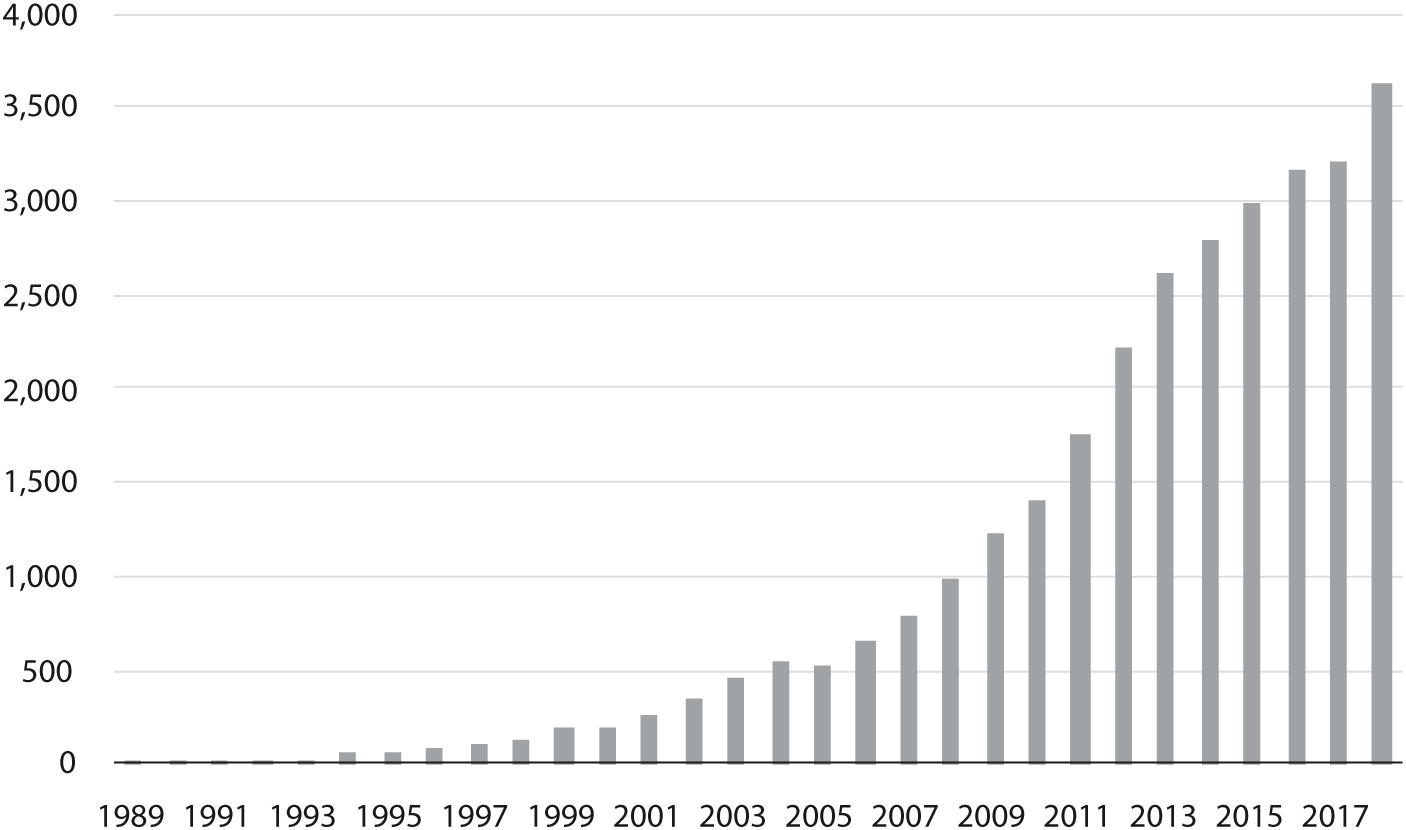

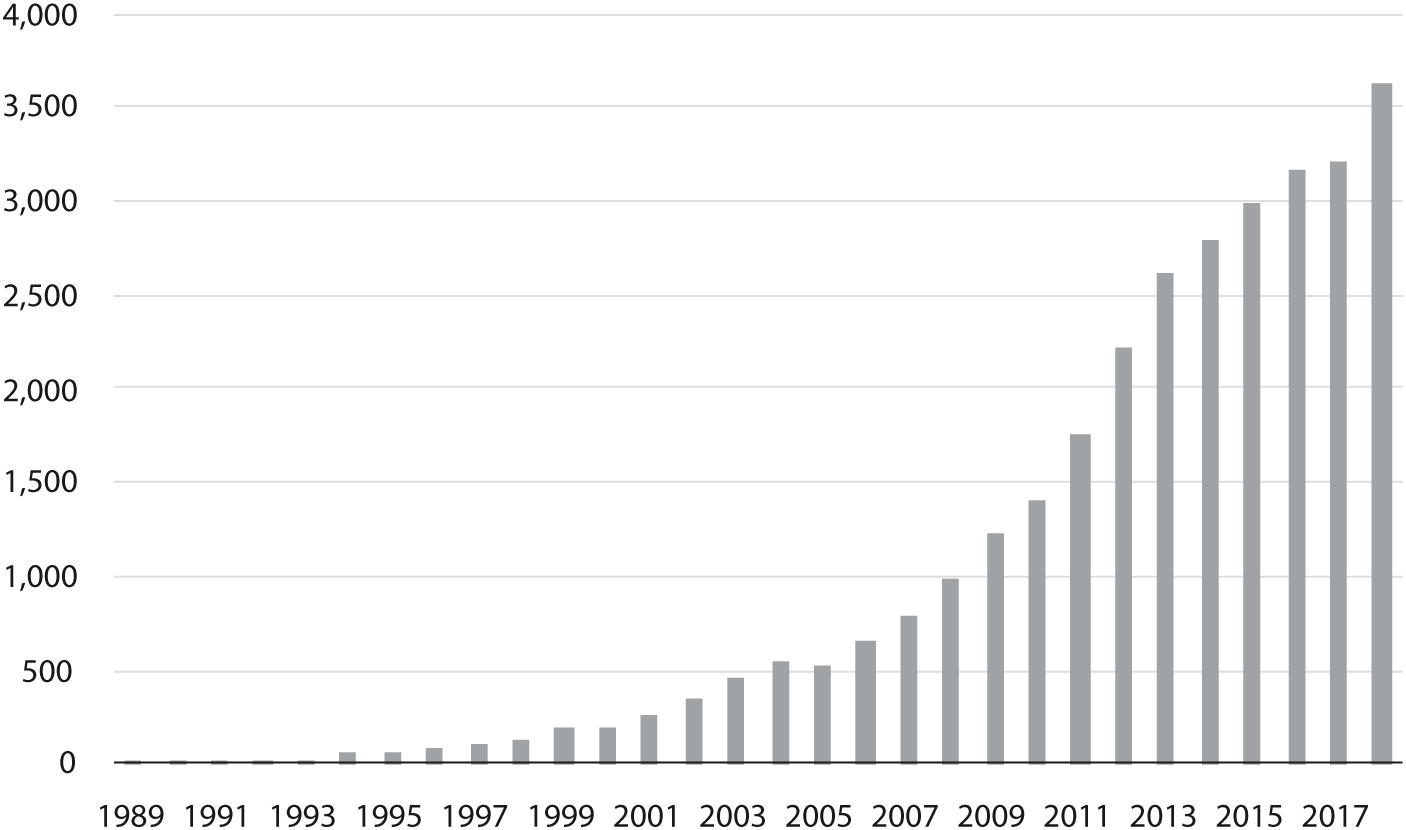

Interestingly, academic interest in school bullying is said to have begun in earnest after several suicides in Norway were linked to bullying (Beaty and Alexeyev 2008). The research was pioneered by Olweus (1993), who in addition to researching the causes and consequences of bullying also developed a leading bullying prevention program. Academic interest quickly spread to neighboring European countries and then additional ones. Research in the United States was slower to start, increasing dramatically after about 2007. Figures 1 and 2 provide representative examples of the steep increase in academic publications concerning school bullying. Each figure represents the number of academic publications returned from a search on the comprehensive academic search engine Google Scholar using the search term school bullying (in quotation marks). Figure 1 shows the number of academic works (e.g., articles, monographs, book chapters, and books) that were added each year, from 10 in 1989 to 3,620 in 2018. Figure 2 shows the yearly cumulative number of academic works, beginning with 10 in 1989 and increasing to 30,399 in 2018. As large as these recent numbers are, they are a vast understatement considering that many academic works on school bullying do not necessarily use the words school bullying in that order. A search of the term without quotation marks yielded 614 hits for 1989 and a cumulative 358,000 hits for the period 19892018. Many of these results are not on point (some results use the two terms but in an unrelated way), so it is not possible to know the precise number of publications.