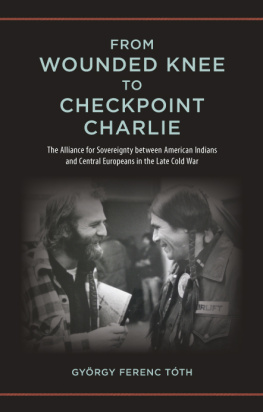

From Wounded Knee to Checkpoint Charlie

SUNY series, Tribal Worlds: Critical Studies in American Indian Nation Building

Brian Hosmer and Larry Nesper, editors

From Wounded Knee to Checkpoint Charlie

The Alliance for Sovereignty between American Indians and Central Europeans in the Late Cold War

Gyrgy Ferenc Tth

Cover photo courtesy of Dick Bancroft and Claus Biegert; photo archive of the Gesellschaft fur Bedrohte Volker, Gottingen, Germany.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2016 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Diane Ganeles

Marketing, Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tth, Gyrgy Ferenc, 1976

Title: From Wounded Knee to Checkpoint Charlie : the alliance for sovereignty between American Indians and Central Europeans in the late Cold War / Gyrgy Ferenc Tth.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, 2016. | Series: SUNY series, Tribal worlds : critical studies in American Indian nation building | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015027729 | ISBN 9781438461212 (hardcover : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9781438461236 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Indians of North AmericaPolitics and government20 th century. | Indians of North AmericaGovernment relationsHistory20 th century. | Indians of North AmericaCivil rightsHistory20th century. | SovereigntyHistory20th century. | Anti-imperialist movementsHistory20th century. | United StatesRelationsEurope, Central. | Europe, CentralRelationsUnited States. | United StatesPolitics and government19451989. | Europe, CentralPolitics and government20th century.

Classification: LCC E98.T77 T68 2016 | DDC 323.1197dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015027729

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In honor of the transatlantic activists for American Indian sovereignty.

Dedicated to my mentors, parents, and grandmother.

Contents

Preface

I was born in 1976in the year of the U.S. Bicentennial. My parents did not get to attend the anniversarys festivities because we lived on the other side of the iron curtainin Communist Hungary. We were far away from the official celebrations sponsored by the U.S. government, and from the counter-commemorations and alternative ceremonies staged by dissenting groups and movements, who reflected, reenacted, and challenged the meaning of U.S. national history and identity.

Yet, in spite of Hungarys official anti-U.S. propaganda, we did engage with American culture. My grandmother, a Baptist faithful even under the toughest dictatorship, was elated when she heard that Jimmy Carter, a Southern Baptist, was elected president of the United States. As for me, some of my earliest memories are of my mother reading to me at bedtime some of Karl Mays novels, in which a young German protagonist goes to the Wild West, strikes up a friendship with an Apache warrior, and together they fight against the evil Kiowa Indians and white bandits. When I was a little older, I acted out some of these stories with a friend of mine. Around this time and later, I would go with my parents to the cinema to watch Westerns made in the Eastern Bloc about the nineteenth-century resistance by American Indians to the U.S. Army and land grabs by white capitalists. Their star, Gojko Mitic, was from Yugoslavia, but for us he was an American Indian. Later still, in the early 1990s, I met a Hungarian hobbyist who told me about the people who had been reenacting American Indian cultures in their summer camps in the hills.

However, no one told me about the American Indian Movements struggles when I was growing up. It was only much later, after long years of learning English at school and at home on TV, after the transition of my country to democracy and capitalism, and once I was majoring in American Studies at university, that I learned about the American Indian radical sovereignty movement. At first I did not make any connections between the Indian fantasies of my childhood and the Native activism on the other side of the Atlantic. As I increasingly used my academic training about the United States to critically examine my own society, I became interested in just what I and millions of other Hungarians (and indeed, Central Europeans) were doing with those fantasies. From recent scholarship I learned to recognize and appreciate the multiplicity of motivations and functions of this Indian play among Europeans. However, what kept intriguing me was the possibility that some of the people who engaged in playing Indian could also perhaps fight for Indian rights. As I became a Hungarian scholar of the politics of U.S. culture in Cold War Central Europe, I embarked on a project to show that cultural consumption and creative engagement with America can lead to not only intercultural encounters, but also to political activism and alliances for social justice across geographical, ideological, and racial divides. Set in the period of my childhood, this is the history of the transatlantic coalition for American Indian sovereignty.

Acknowledgments

This book was written about a select group of people who worked hard for their ideals. As such, the project benefited from the contributions of a select group of peoplefriends, colleagues, and professionals.

During my research trips I received in-kind logistical assistance from Su Zhang, Carlton Rounds and Michael Cabbie Caban, Leslie Holland and Jack Lamb, Carmen Samora, Betsy Loyd and Kol Harvey, Colleen Kelley, Abby Kaiser, and Danielle Dahl.

My research benefited greatly from the assistance of Anna Bnhegyi, Colleen Kelley, Vera Grabitzky, Adrienn Kcsor, Zsuzsanna Horvth, Claus Biegert, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, H. Glenn Penny, Martin Klimke, Trudy Peterson, and anonymous Hungarian hobbyists of American Indian cultures.

During my research trips I relied on the professional services of the staff of the Minnesota Historical Society; Leah Jehan and the staff of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University; the staff of the National Archives II in College Park, Maryland; the staff of the United Nations Archives in New York City; Donald Burge and the staff of the Center for Southwest Research of the University of New Mexico; the staff of the Library and the Archives Registry Sub-Unit at the United Nations Palace of the Nations in Geneva, Switzerland; the staff of the Federal Archive, Reich and GDR Department, Archive of the Parties and Mass Organizations of the GDR; and the staff of the Federal Commissioner for the files of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic, Berlin, Germany.

My research of the organizational records of the transatlantic sovereignty alliance would not have been possible without the kind help of Alberto Saldamando and the staff of the International Indian Treaty Council, San Francisco; Pirrette Birraux and the staff of the Indigenous Peoples Documentation Center in Geneva, Switzerland; Helena Nyberg and the staff of INCOMINDIOS in Zrich, Switzerland; and Yvonne Bangert, Tilman Zlch, and the staff at the Gesselschaft fr Bedrohte Vlker in Gttingen, Germany.