FULL COURT

PRESSRace, Rhetoric, and Media Series

Davis W. Houck, General Editor

FULL COURT

PRESS

Mississippi State University, the Press, and the Battle to Integrate College Basketball

Jason A. Peterson

University Press of Mississippi / Jackson

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2016 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2016

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

978-1-4968-0820-2 (hardback)

978-1-4968-0821-9 (ebook)

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Contents

Acknowledgments

I would like to begin by acknowledging the contributions of the many journalists and athletes cited in this volume, some of which displayed great courage and foresight. Even now, I marvel at the conviction of many of the individuals featured in this book, and I thank them for making social progress a priority in the face of such adversity. Wilbert Jordan Jr., Perry Wallace, Joe Dan Gold, Dr. Douglas Starr, Jimmie McDowell, Joe Mosby, Rick Cleveland, and Bob Hartley all contributed to an overall understanding of the civil rights era, and the commentary offered by each validated my exploration into this topic.

I would also like to thank my friends and mentors David R. Davies and Brian Carroll. Both men were instrumental in my completion of this volume, and without their guidance and wisdom, I doubt I would have completed such a task. Also, in no particular order, I would also like to thank the following individuals for their assistance and guidance: Art Kaul, Gene Wiggins, Dan Fultz, Thomas Keating, Bob Frank, Curt Hersey, Diane Land, Kevin Kleine, Thomas Kennedy, Kim LeDuff, Cheryl Jenkins, Christopher Campbell, Ginger Carter Miller, Mary Jean Land, William Griswold, Louis Benjamin, Mazharul Haque, Bradley Bond, Louis Kyriakoudes, Willie Pierce, Betty Self, Jennifer Ward, John Wall, Andrew Sharpe, Pristina Armstrong, Jennifer Brannock, Cindy Lawler, and Xiaojing Zu.

On a personal note, I would like to thank my parents, William and Sandy Peterson, for fueling my thirst for knowledge over the years, and my brother, Billy Peterson, who jokingly doubted my sanity during my years as a journalist, yet never questioned my dreams and aspirations. He has remained a steady and supportive influence in my life and, for that, I will always be grateful.

Last, but not least, I would like to thank my wife and my two children. An endeavor of this magnitude would not be possible without their unconditional love, support, and encouragement. My wife has never questioned my desires to achieve this goal and lovingly followed me on a trek through the southern United States. She is my best friend and my biggest fan. There is no doubt that I would have been unable to complete such an arduous task without her. Joy, Addison, and Connor, this is for you. I love you.

FULL COURT

PRESSIntroduction

The civil rights era in Mississippi was a dark and violent time in our countrys history. While the rest of the southern states moved on from the heated debate concerning the extent of states rights and began to catch up with their northern brethren, Mississippi held firm in its believed right to segregate. Notions like equality and integration into the traditionally white customs and social structure of the Magnolia State were cast aside with vigor and rage. While the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision was supposed to alleviate some of the dominance of Mississippis white elite, the groundbreaking legal precedent only helped strengthen the foundation on which the Closed Society was built. Governor Hugh White responded to what has been called Mississippis Second Reconstruction by continuing with his plan to develop segregated, white-only schools rather than integrating existing educational establishments.

From the mid-1950s through the late 1960s, Mississippis white-dominated caste system, dubbed the Closed Society by historian James Silver, permeated every segment of society and, for better or worse, had a profound influence on how whites and blacks in the state lived. The social and political atmosphere emphasized a belief in white supremacy through segregation, which was rationalized by an appeal to states rights.journalism during the civil rights era and assist in the deconstruction of the Closed Society.

In 1955, after Jones County Junior Colleges football team lost to the integrated Tartars of Compton Junior College in the Junior Rose Bowl, the states political elite banded together with the State College Board to create the unwritten law, a gentlemans agreement, that would keep Mississippis athletic venues segregated and in compliance with the Closed Society. Despite the legal failures of other southern states, the unwritten law endured in Mississippi and was the only one of its kind in the South.

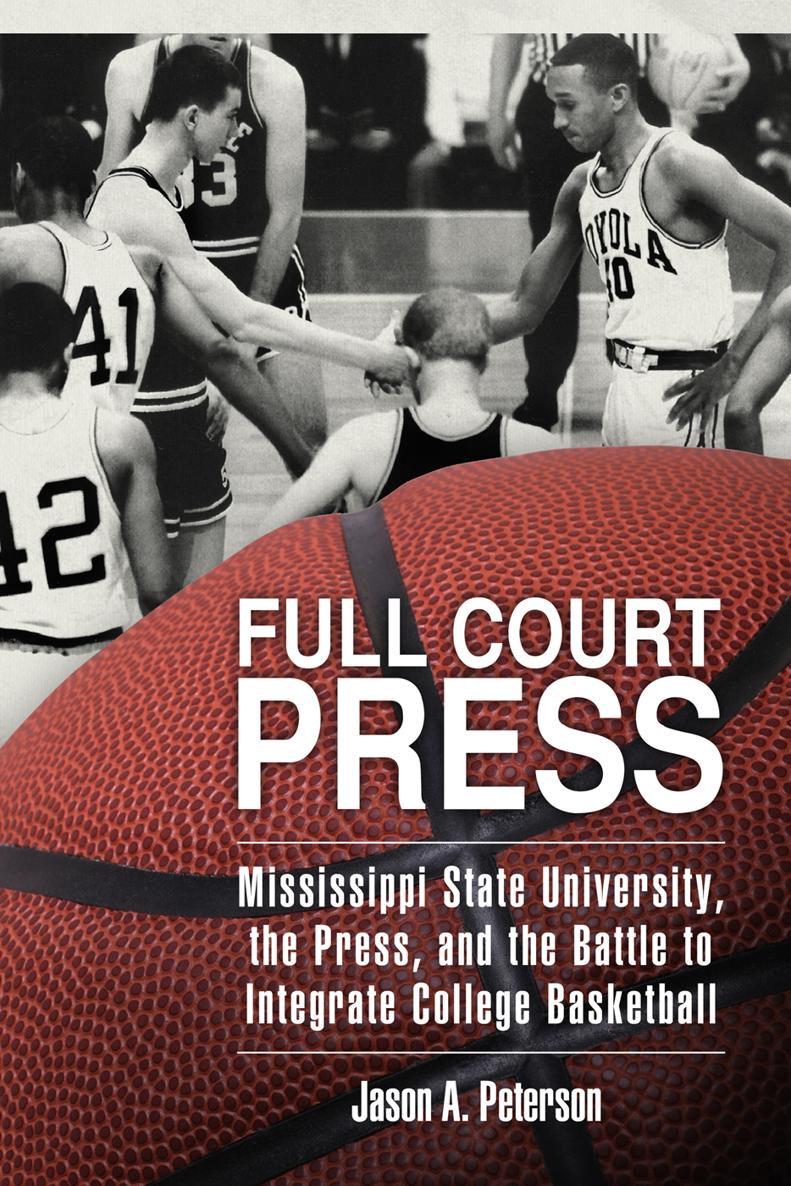

While the Magnolia State was covered in a veil of oppression, a surprising enemy of white supremacy emerged in the small college town of Starkville. Mississippi State University was at the forefront of the battle for equality in the state with the schools successful collegiate basketball program. When Mississippi State was granted university status in 1958, the Maroons won four consecutive Southeastern Conference championships from 1959 through 1963 and created a championship dynasty in the Souths preeminent college athletic conference. However, in all four title-winning seasons, the press feverishly debated the possibility of an NCAA appearance for the Maroons, culminating in Mississippi State Universitys participation in the 1963 NCAAs National Championship basketball tournament, where they lost to the integrated Loyola of Chicago.

During the unwritten laws eight-year existence, the hardwood of Mississippis college basketball courts brought forth multiple challenges to the Closed Society, all of which were debated with fervor and spite in the pages of Mississippis newspapers. While the basketball teams from the University of Mississippi, the University of Southern Mississippi, and Jackson State College would all experience the repercussions of the unwritten law, it was Mississippi State that was the most frequent challenger of Mississippis segregated athletic standard. Mississippis editors and journalists overall expressed polarizing opinions on the merit of integrated athletics, which ultimately damaged the Closed Societys racial united front.

An examination of Mississippi newspapers during the eight-year existence of the unwritten law shows that the various challenges placed before the gentlemans agreement, specifically those posed by Mississippi State University, generated three primary responses from Mississippis journalists. Reporters and editors either condemned or dismissed any threats to the unwritten law, voiced no opinion on the possibility of integrated competition and published little or no original material on the matter, or supported a venture into integrated play, more often than not only to better Mississippis chance at a championship. For each expression of outrage, the press gave the unwritten law a degree of credibility as a vital and crucial part of Mississippis white way of life, and helped enforce the segregated standard. Furthermore, the legitimacy of the unwritten law was perpetuated by the silence from Mississippis sports writers, who typically hid in the comfortable confines of athletics and rarely addressed the racial controversy surrounding each of these challenges. While silence from the press can be taken to mean different things, Richard Iton argues that intentional silences also have significance: to say nothing suggests acceptance of, or satisfaction with, existing arrangements, and implicitly represents the expression of a political preference. The emergence of racial connotations in athletic endeavors, in this case MSU basketball, was ignored because it forced the Closed Society to question its own superiority and unity. Consequently, the sports scribes of the state found little news value in the pioneering presence of Jordan, of Coolidge Ball at Ole Miss in 1970, or of Larry Fry or Jerry Jenkins at Mississippi State in 1971, rarely identifying the athletes skin color. The silence that once served the journalistic stalwarts of the Closed Society slowly became a nod to the social progress made by the members of the press, as the integration of sports was no longer a source of polarizing opinion from reporters and editors.