Emerald Publishing Limited

Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley BD16 1WA, UK

First edition 2021

Copyright 2021 Dariusz Dziewanski

Published under exclusive licence by Emerald Publishing Limited.

Reprints and permissions service

Contact:

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. Any opinions expressed in the chapters are those of the authors. Whilst Emerald makes every effort to ensure the quality and accuracy of its content, Emerald makes no representation implied or otherwise, as to the chapters' suitability and application and disclaims any warranties, express or implied, to their use.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-83909-731-7 (Print)

ISBN: 978-1-83909-730-0 (Online)

ISBN: 978-1-83909-732-4 (Epub)

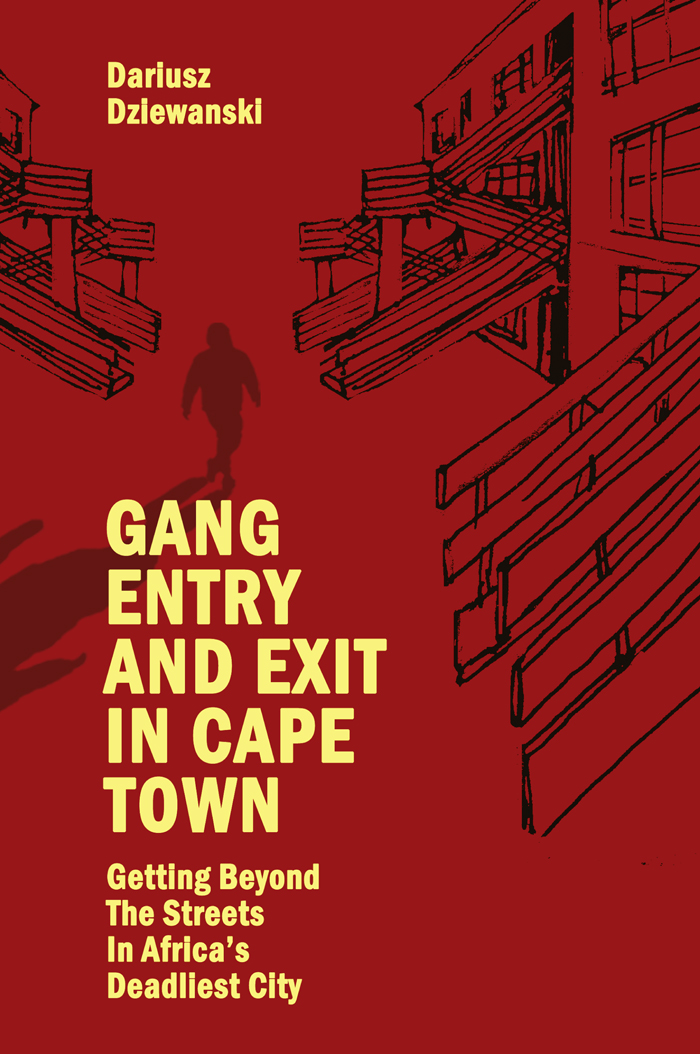

Preface

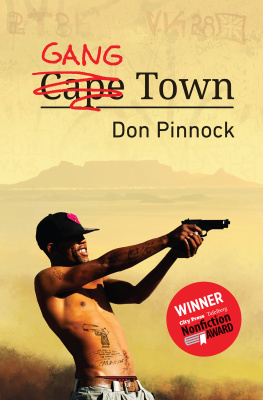

At the heart of it, ethnography is about stories. The ethnographic research this book is based on is a collection of personal histories from young people attempting to leave gangs and rebuild their lives in Cape Town, South Africa one of the most segregated and deadliest cities in the world. Their stories connect to a more profound narrative about a country that itself is still attempting to recover after losing generations to the tyranny of racial persecution under apartheid. Anybody insisting that characters, setting, plot and conflict must necessarily find a satisfying resolution at the end of a story might find the following pages vexing. They are full of frustrated intentions and unresolved endings. Each person in this publication has left gangs, sure. But each is to this day in his or her own way wrestling with a familiar list of personal and social issues; the joblessness, racism, isolation and hopelessness that drove them into gangs in the first place, still to a large extent continue to define their lives as ex-members. That such difficulties persist even after exit makes their narratives no less compelling. One could argue persuasively, actually, that it is all the more necessary for this reason to give voice to stories like these. They serve as a lamentable reminder of the tragedy and bravery that define the existence for the majority of young men and women in Cape Town both inside and outside of the streets.

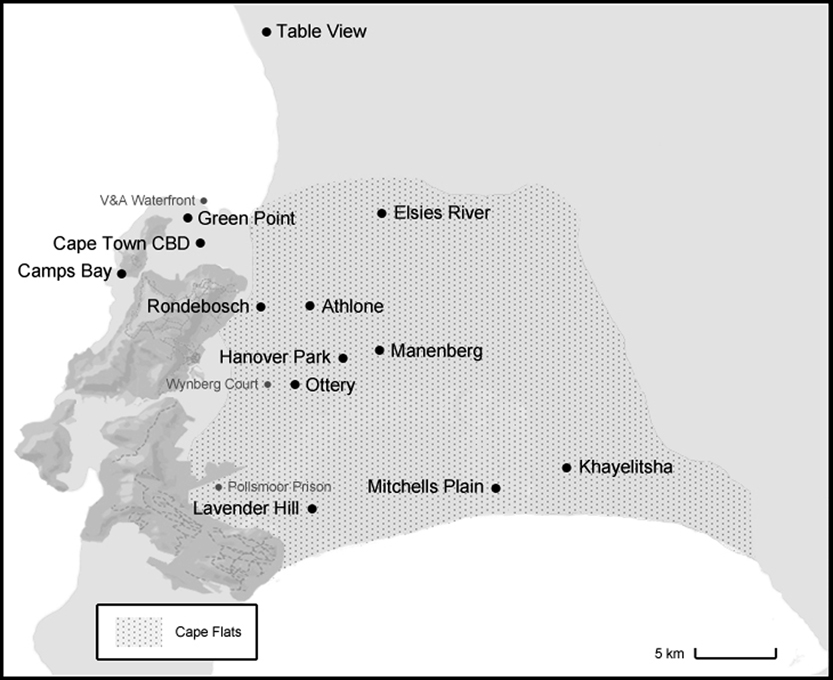

Let us recognise one person, in particular, whose story is central to this book. Gavin (Ottery male, 30 years)1 had spent over half of his life in gangs when I met him. He was still, at that point, a prominent member of both the Mongrels street gang and the 28s prison gang. Our introduction came at a halfway house Gavin was released to after serving a ten-year murder sentence in the notorious Pollsmoor Prison, a maximum security penal facility that holds some of South Africa's most dangerous criminals. That was in 2013, shortly after I landed in Cape Town to begin this project. Our paths would proceed to intertwine over the next years in the labyrinth of sheet metal, distressed wood and dust that make up the patchwork of squatter camps or kampies 2 hidden in and around the Capetonian suburb of Ottery. The predominately poor and working-class neighbourhood is situated some 20 minutes by car southeast of downtown, and is the place where Gavin's gang, the Mongrels, have their headquarters. The Mongrels are one of the city's biggest and oldest gangs, tracing their origins back to Cape Town's historical District Six neighbourhood. Today, their MG insignia claims walls, buildings and bodies in their stronghold of Ottery, just as the names of gangs like the Americans, Sexy Boys, Hard Livings, Junky Funky Kids, Laughing Boys and the Ghetto Kids dominate communities such as Hanover Park, Manenberg, Mitchells Plain and Delft. I would come to know many of these areas well, spending hundreds of hours talking to and hanging out with the men and women who live there. Our shared interactions offered a vivid view of the physical contexts and felt experiences of Cape Town's township communities, helping to dispel some of the preconceptions that inevitably arise when outsiders like me attempt to break into, comprehend and depict an unfamiliar moral universe.

One of my first entries into a township was with Gavin, in fact. I accompanied him on a trip to a kampie near Ottery, where he was controlling sales of tik, unga, dagga and buttons3 for the Mongrels. It is a part of Cape Town where my white face was undoubtedly as unusual to the residents there as their community was to me. Gavin offered some words in preparation as we entered the settlement. Don't be scared [when we arrive]. You must be a motherfucker. You must just be like: I don't give a fuck; like, gangster bro, he declared with a laugh. You musn't show people you [have] fear or they will take you for poes.4 I dismissed his advice as good-natured teasing, and did not give it much thought, preoccupied as I was with maintaining my footing as we snaked through the kampie's dim and uneven passages. I would later come to appreciate that Gavin was conveying to me a very important lesson: there are places in Cape Town where your security cannot be taken for granted, where you have to nonstop stand up for yourself or you risk being labelled vulnerable and being made into a victim. I do not mean to sensationalise our trip that night. It passed without trouble. Yet, it was also undeniably saturated with a series of small, spirited provocations. Most were projected through the haze of smoke, voices, bodies and beats of a shebeen,5 where Gavin's gang brothers intermittently goaded me into fictitious quarrels and confrontations, trying to see if I would take up their theatrical displays of aggression. It was also in the shebeen where a group of women demanded that I show them how the white man dances, their insistence punctuated by laughter and suggestive gyrations. Another group of tipsy middle-aged men kept insisting that my foreignness and presumed affluence obligated that I buy them a bottle. Underlying their jocularity seemed to be a hope that I would relent as the joke wore on. I almost did.

Others pushed and prodded in their own ways. Occasionally Gavin would interject protectively. Sometimes he would leave me to fend for myself, or would physically and verbally urge me towards the tumult, to the great delight of onlookers. As the night progressed I started to suspect that what I was being pulled into was a type of trial, to ascertain if I could establish myself as a motherfucker according to the logic Gavin outlined beforehand. This suspicion was confirmed when he later confessed at one point intentionally leaving me alone, when going to tend some business matters in another part of the settlement. Yeah, I left [you], just to see how you handle it see if you could be a motherfucker, he revealed with a smirk.