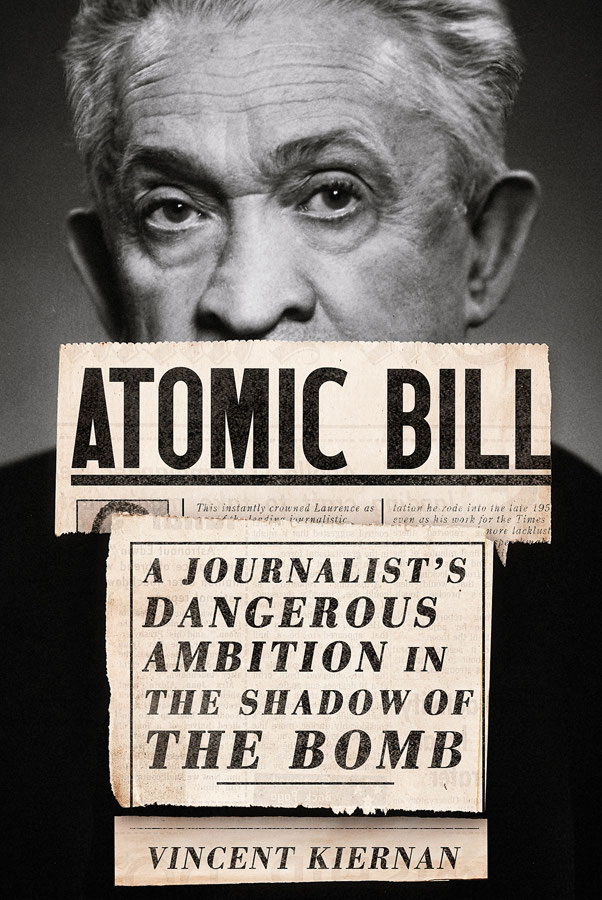

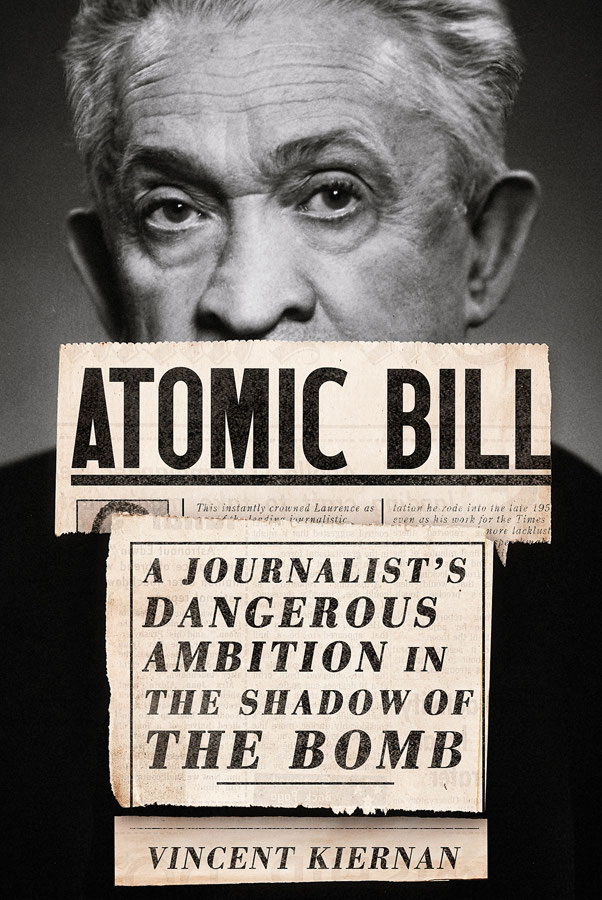

Atomic Bill

A Journalists Dangerous Ambition in the Shadow of the Bomb

Vincent Kiernan

Three Hills

an imprint of

Cornell University Press

Ithaca and London

For Terri, Emily, and Matthew

Contents

Introduction

A Moth to the Flame

In just less than one year, an extravaganza of science and technology would be opening on a former garbage dump in Queens, New York: the 196465 New York Worlds Fair, expected to attract 55 million visitors with a gleaming vision of the future. For years, William Leonard Laurence, the famed science writer for the New York Times, had been quietly paid by fair president Robert Moses to help plan and promote the fair even as Laurence still worked for the papera glaring ethical violation for Laurence. But on that day in April 1963 Laurence committed an even worse infraction: while the papers editorial-page editor was out of town, Laurence had the paper run an editorial calling on New York City to fund a permanent science museum at the fairgroundsand proudly shared the editorial with Moses before it appeared in print. The next day, Laurence doubled down on his ethical trespass by testifying before a city appropriating board in favor of the expenditure. It was all of a piece for Laurence, who throughout his storied career, covering the atomic bombings of Japan as well as many other landmark stories in science and technology, ignored ethical and professional rules in order to satisfy his thirst for status and money and his desire to cozy up to the powerful and rich.

Journalists like Laurence have always been societys chroniclers of the momentauthors, in the phrase of uncertain provenance, of the first rough draft of history. During the Civil War, reporters trekked along with the battling Union and Confederate armies and raced to get their dispatches to their newspapers by telegraph. At the turn of the nineteenth century, muckraking journalists horrified and disgusted readers with stories of filthy meatpacking plants and corrupt politicians, triggering crusades to clean up both. Today journalists sit in meeting rooms or watch streaming video feeds to keep tabs on the work of city councils and congressional committees.

For decades these authors of historys rough draft were usually uneducated scribblers, with no special expertise in the specific stories or topics they covered. Often moving together in a pack, these reporters from various publications scrambled from one story to the next, like the band of jabbering reporters memorialized in the 1928 Broadway play and 1931 film The Front Page. These reporters needed no particular expertise because their work had no particular focus: one day a reporter might cover a downtown fire; the next day, a municipal scandal. The work was all about the big story of the day, whatever it might be, and the reporters often seemed largely interchangeable with one another.

That was just fine with their editors and publishers, who sought to publish newspapers and magazines that appealed to the largest audience possible. Although occasional journalistic stars would emerge, reporting by and large was a fairly anonymous, blue-collar job with little job securityreporters knew that scores of would-be reporters would jockey after every position and were perfectly qualified (or as unqualified as anyone else) for it.

Around the start of the twentieth century, the modernizing of society began to wreak ripple effects on this journalistic ecosystem in many ways. One was the fact that the emergence of modern science created new products and technologies that touched the lives of Americanselectric lighting, aviation, early physics, the beginnings of modern medicine. During World War I, technology was a terrible and potent sword in the hands of both the Allies and the Central Powers. Chemical warfare, radio, and machine guns were among the technological advances that soldiers and their families back home came to know about. Editors and publishers began to perceive a public hunger for news about science, medicine, and technologyand with that hunger, a market opportunity, if only the publishers could employ reporters with the skills needed to find and report those stories. Gradually, a new generation of reporters focusing on science, medicine, and technology began to emerge. For example, Herbert B. Nichols was named natural science editor of the Christian Science Monitor in 1928, and Thomas R. Henry became science writer for the Washington Star in 1929. New York Times reporter Alva Johnston covered the 1922 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for which he received a Pulitzer Prize.

It was the beginning of an essential era in journalism. In light of the degree to which todays society is drenched in science and technology, journalism and journalists truly would have been guilty of professional malpractice if they had not developed the ability to identify, interpret, and report on developments in science and technology. But with that task came great responsibility, a responsibility that journalists have not always satisfied.

Physics, for example, was one of the most exciting fields of science at the start of the twentieth century. The structure of the atom, not to mention its potential for releasing enormous quantities of energy, was completely shrouded in mystery. While schoolchildren today can relate the basics of the atom, with the nucleus at its center and electrons spinning around it like planets orbiting the sun, the worlds top scientists spent the early decades after 1900 debating and refining what exactly was happening in the atom. Meanwhile, soon after 1900, Albert Einstein formulated special relativity and general relativity, two theories that set theoretical physics and astronomy back on their heels.

At this time, Laurence was an up-and-coming aviation reporter at Joseph Pulitzers New York World, a pioneer of yellow journalism, the extensive use of sensationalism and scandal to build readership. The forty-one-year-old had spent his early career in a zig-zag, combining time at Harvard University with a trial run in journalism at the Boston American, army service in World War I, and attainment of a law degree before finally resolving to enter journalism full time at the World. On New Years Eve in 1929 he caught the assignment of covering a lecture by James MacKaye, a Dartmouth professor who claimed he could disprove Einsteins theory of relativity. Although Laurence privately realized that MacKaye knew little about Einstein, Laurence plunged ahead with a story with the style that he would perfect at the Times, combining breathless enthusiasm for unreliable research with a didactic approach that would land his story on the front page. He made MacKaye look like a genius, stating that MacKaye had presented a new theory of the universe pronounced by scientists and philosophers as epoch-making and far-reaching in its consequences, and differing radically from the Einstein theory of relativity. Then Laurence described the scientific reaction to the lecture: After a moment of impressive silence as he finished reading, the staid academic halls resounded to the sound of hearty applause. On the following Sunday, Laurence followed up with a lengthy feature story describing MacKaye and his theories.

Within months, the Times would hire Laurence, and he would promptly begin writing stories about atomic research. Encountering each other again and again at scientific conferences and events across the country, Laurence and science reporters from other newspapers and wire services would forge a new type of journalistic pack, one focused on the reporting of science and technology. They realized that being scooped by others in the pack would draw criticism from faraway editorsmuch more than the praise an editor would make for having a scoopso they often would agree among themselves about what was newsworthy and what was not about a story, and when it could be released as news, so that they all knew what the others were going to do.

Next page