Table of Contents

For Marjorie, Ben and Francine Achbar

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people were involved in the process of putting this book in your hands.

My sincere thanks to:

Peter Wintonick and Francis Miquet, my friends and partners, for allowing this project to usurp some of Necessary Illusions meager resources;

Linda Barton and Dimitrios Roussopoulos of Black Rose Books, for their encouragement and confidence;

Rodolfo Borello and Andrew Forster, for their design sensitivity and their professionalism in working to an impossible deadline;

Jane Broderick, for copy editing the book and creating the index, to the same impossible deadline;

Merrily Weisbord and Robert Del Tredici, my mentors in the medium of print;

Caroline Voight, Stacy Chappel, and Robert Kwak for their command of the keyboard, and Susan Grey, for her additional research;

Blake Gulband and Nat Klym, for their practical advice;

The National Film Board of Canada, especially Steven Morris, Trevor Gregg, Maurice Paradis and David Verrall, for their cooperation and technical support;

David Pollack, of Inframe Productions, and Colin Pearson, for their generous contribution of image grabbing technology, and Jason Levy for his time;

Martine Cote and Kate McDonell, for their help in processing the images;

Tom Tomorrow, for his illustrated attitude;

James McGillivray, for finally delivering the cards;

Cha Cha Da Vinci and Leah Lger for keeping their zapper on the pulse of Springfield;

Christine Burt, for her tactful assessments;

Elaine Shatenstein and Cleo Paskal, whose editorial comments substantially improved the quality of this effort;

John Schoeffel, for his useful suggestions throughout;

David Barsamian, whose interviews added so much to the film and this book;

Carlos Otero, for his example and help with setting priorities;

Sabrina Mathews, whose curiosity guided much of the substance of the additonal material and whose stamina kept the machine running;

Edward S. Herman, whose chapters in Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media provided the unifying concepts behind much of our film;

Carol Chomsky, for her generosity in providing and reproducing family photos for the film and for her support and corrections on the rough cuts.

And to Noam Chomsky, whose work has been the focus of mine for over six years, for his encouragement, his inexhaustible energy, his willingness to respond to all our questions and requests, and for his bemused tolerance of our cameras, which made possible the film on which this book is based.

INTRODUCTION

Having been active in the peace and anti-nuclear movements in the early 1980s, I was drawn, in 1985, to a talk entitled The Drift Toward Global War, by Noam Chomsky. The speakers name was familiar to me but the ideas it represented were not. The long, oak-paneled hall at the University of Toronto was filled well beyond capacity. I set up my tape recorder near the podium just in time for the superlative-strewn introduction. Applause, then Chomsky, and down to business. Every 45 minutes I quickly flipped my cassette, or inserted a new one, anxious not to miss a word.

That night, a soft-spoken man with a dark, ironic sense of humor, and a command of facts I had never before encountered, irrevocably shifted my political paradigm. After what seemed like minutes of sustained applause, I apprehensively approached the mild-mannered speaker with others for whom two and a half hours was not enough. For a moment, no one spoke. There was an awe-struck lull, which I shattered, intruding on his personal space with my microphone for the first of many times. I found a tolerant, empathetic man prepared to patiently rearrange the oxide on my cassetteand my understanding of the abuse of power in the world.

Regardless of the ineloquence of the question, Chomsky immediately grasped the intent, and answered, I later came to realize, at the same level at which he would answer a historian interviewing him for the BBC. I was struck by his utter lack of condescension. That moment, and many others Ive since witnessed and filmed, are, I believe, deep reflections of Chomskys faith in the ability of so-called ordinary people to understand and act on the issues he raises. He actually tries to live the egalitarian philosophy he espouses.

I listened to the cassettes I recorded that night many times over the next two years. And I kept an eye and an ear out for Mr. Chomsky, regularly scanning the mass media. But he was nowhere to be found. You could dig up his books if you hunted in the right stores, but he wasnt out there in any appreciable way.

Fortunately, in 1987, at the invitation of Dimitri Roussopoulos, the publisher of this book, Chomsky came to speak at Concordia University in Montreal, the city I then called home. Again, the hall was filled to overflowing. I sat with Terri Nash, whose Oscar-winning film, If You Love This Planet, based on a a lecture by anti-nuclear activist Helen Caldicott, was reaching substantial audiences in schools and on television. I remember thinking, Maybe I can do for Noam what Terri did for Helen.

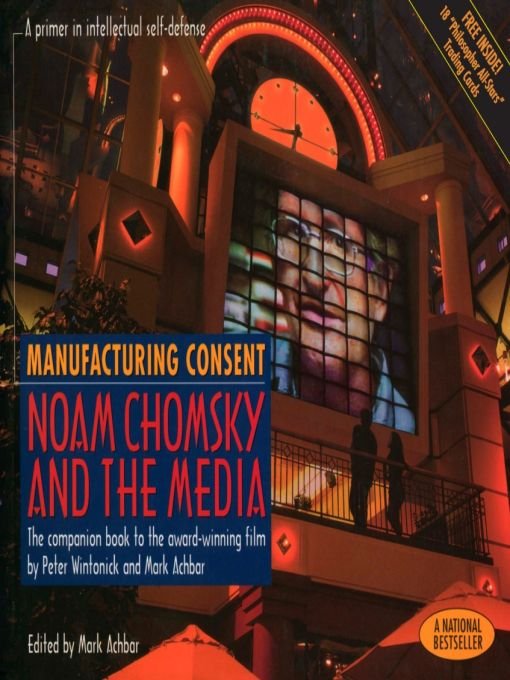

This book, like the film on which it is based, is designed as a stepping-stone to related texts by Chomsky, Edward S. Herman, and others and to organizations active in a range of issues. I have presented a complete transcript of the film, and, as topics arise, have sought out relevant passages from different sources, though mainly from Chomskys writings, talks and interviews, which offer further insight, with the hope of enticing the reader back to the source. The Resource Guide, beginning on page 239, lists several non-mainstream organizations and sources of information in print, audio, film, video, and on computer networks. I consider this Resource Guide as a work-in-progress and welcome suggestions for additions and improvements in future printings.

In reviewing an early draft of this book, Chomsky expressed reservations about the utility of the format. Although several collections of his talks and interviews have been published, to my surprise he questioned the ability of the spoken word transcribed, as compared to the written word in articles and books, to clarify issues: The more considered and careful versions that reach print in the normal course of affairs, he wrote, are far preferable. He voiced this concern along with eight single-spaced pages of much-appreciated notes aimed at improving this book. Several are included verbatim.

While they are more precise and detailed than extemporaneous talks can be, Chomskys writings are also more complex, dense with references, grammatically sophisticated, and often assume substantial prior knowledge. Chomsky is an impressive yet plain-spoken verbal communicator and many find those words transcribed to be an accessible route to his thinking. The popularity of his talks and interviews published in various forms attests to this. Both have value, I think, and are mutually reinforcing.

As in the interview excerpt which follows, Chomsky also expressed concern about the personalization of issues. This posed a dilemma for Peter Wintonick and me as filmmakers and has again to some degree with this book. In making the film, we felt it was impossible, indeed undesirable, to divorce the man and his ideas from the personal history that helped shape those ideas. Our basic criterion for inclusion of biographical information was: does it bear on Chomskys political formation?