REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF THE CRATER

REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF

THE CRATER

War as Murder

KEVIN M. LEVIN

Copyright 2012 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 405084008

www.kentuckypress.com

16 15 14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Levin, Kevin M., 1969

Remembering the Battle of the Crater: war as murder / Kevin M. Levin.

pages cm (New directions in Southern history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-3610-3 (hardcover: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-3640-0 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8131-4041-4 (epub)

1. Petersburg Crater, Battle of, Va., 1864. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Participation, African American. 3. United States. ArmyAfrican American troopsHistory19th century. 4. African American soldiersHistory19th century. 5. United States. Colored Troops. 6. Collective memory. I. Title.

E476.93.L48 2012

973.736dc23

2012012438

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

For Ela

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

IN DECEMBER 2003 moviegoers were treated to a vivid re-creation of the battle of the Crater in the movie Cold Mountain, directed by Anthony Minghella. Though the battle, which was fought just outside Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864, was not included in the original work of fiction by Charles Frazier, it was used in the film as a dramatic opening to set the stage for Inman (played by Jude Law) and his decision to leave the Confederate army and head back to his lover (played by Nicole Kidman), still living in western North Carolina and working desperately to make ends meet. The opening sequence presents the important stages of the battle, including the initial massive detonation of explosives under a Confederate salient, the advance of Federal soldiers into the crater, and the hand-to-hand combat that left thousands dead and wounded, resulting ultimately in a decisive victory for General Robert E. Lees Army of Northern Virginia.

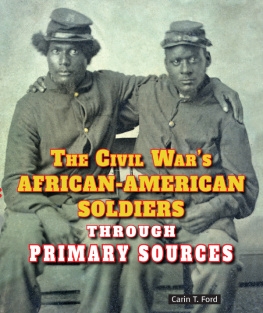

The movie accurately portrayed the bloody fighting in and around the crater and probably satisfied the demands of most Civil War enthusiasts. The movie also briefly acknowledged the presence of United States Colored Troops (USCTs). At one point in the battle sequence, a black Union soldier and a Native American in Confederate uniform exchange glances. Minghellas negotiation of the race issue, however, avoids any references to the well-documented executions of many black soldiers after their surrender.

Minghellas historic representation of the battle of the Crater takes its place in the long and complex history of race and Civil War memory stretching back to the accounts that the soldiers themselves wrote after the battle. If we step back, however, it is impossible not to acknowledge the wide gulf, with regard to race, between the accounts the soldiers wrote and the way subsequent generations remembered and commemorated the event, from the nineteenth century up to the eve of the Civil War sesquicentennial.

It is the absence of race, exemplified here in Cold Mountain, that is the subject of this book: this process of preserving a certain kind of memory that moves to minimize or ignore the participation of USCTs in one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. Understanding how memory of this racial component was shaped at various points during the 150 years since the end of the war allows us the opportunity to peer into the changes and challenges experienced by the nation at large. More important, the study of memory allows us to understand the extent to which previous interpretations of the past were subject to political, social, and economic pressures, and how difficult it was for individuals and communities outside of dominant power structures to preserve and commemorate their preferred understanding of the past.

This book has benefited from the vast amount of research that has been done over the past few decades on the Civil War and historical memory. It is not surprising that historians have embraced the study of Civil War memory. The Civil War is ideally suited to an examination of the cultural, social, and political shifts that have shaped our understanding of this nations defining moment. One does not need to look far for evidence of the competing claims on history made by different social groups active in the decades following the war. From research on the influences of the Lost Cause to the role of national reconciliation to the examination of individual battles, monument dedications, textbooks, childrens literature, and commemorative rituals, the focus on memory has aided in uncovering the fluid cultural, political, and racial factors that, in large part, determined whose understanding of the past became legitimized and integral to the formation and maintenance of an evolving national identity.

In many ways this book builds on the scholarship of David Blight, whose book Race and Reunion introduced a readership to the subject of historical memory, a subject extending beyond the narrow confines of the academy. In Blights view, the veterans on both sides of the Potomac chose to assign the deepest meaning of the war to the heroism and valor of the soldiers on the battlefield. The shared experiences of soldierhood was a theme that could bring former enemies together peacefully on old battlefields.

Readers will find elements of Blights thesis throughout this book, but my analysis of memory at the Crater will reveal places where his examination of the multiple traditions that came out of the Civil War does not go far enough in explaining the interplay of race and politics in national reconciliation as well as the deep divisions between former Confederates and white Virginians. Confederates who fought in the Virginia brigade at the Crater were united in their defense of Petersburg from black Union soldiers. This was the first time that Lees men were forced to fight former slaves, and the rage they feltwhich led to the well-documented slaughter of captured black soldiers after the battlereflected, like nothing else could, just what was at stake in the event of Confederate defeat. Confederates experience at the Crater, including their participation in one of the final decisive victories in Virginia, served as a foundation for reunions among the veterans of the brigade in the 1870s on the old battlefield. However, these continued bonds of affection were not immune from the political disputes connected to Virginias fragile postwar racial hierarchy.

Next page