Lawrence Wright

IN THE

NEW WORLD

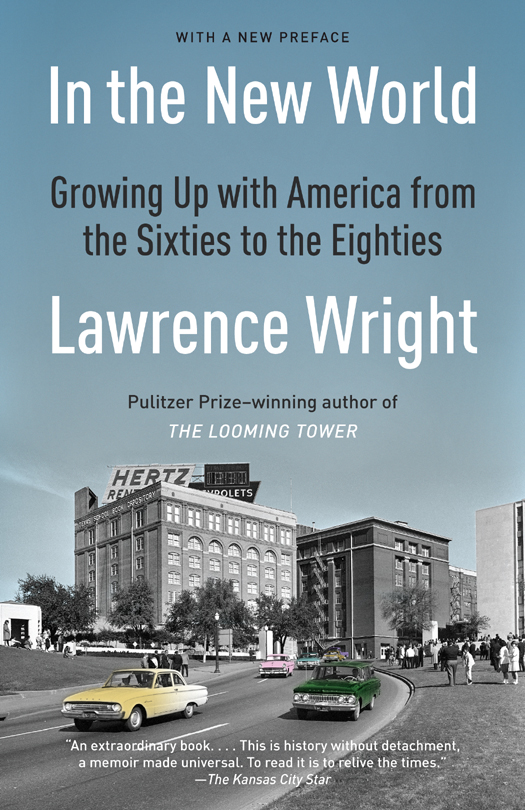

Lawrence Wright graduated from Tulane University and spent two years teaching at the American University in Cairo, Egypt. He is a staff writer for The New Yorker and a fellow at the Center on Law and Security at New York University School of Law. The author of five works of nonfiction, including the the Pulitzer Prizewinning The Looming Tower, he has also written a novel, Gods Favorite, and was cowriter of the movie The Siege. He and his wife are longtime residents of Austin, Texas.

BOOKS BY LAWRENCE WRIGHT

The Looming Tower

Gods Favorite

Twins

Remembering Satan

Saints and Sinners

In the New World

City Children, Country Summer

SECOND VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, FEBRUARY 2013

Copyright 1983, 1986, 1987, 2013 by Lawrence Wright

All right reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in slightly different form in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1987.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Portions of this book were originally published in slightly different form as Why Do They Hate Us So Much in the Texas Monthly.

The Nixon Age was originally published in slightly different form as Why We Liked Dick in The Washington Monthly.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Chappell & Co., Inc.: Excerpt from the song lyrics Camelot by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe. Copyright 1960 by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe. All rights administered by Chappell & Co., Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Decay Music: Excerpt from the song lyrics Riot by the Dead Kennedys.

Copyright 1982 by Decay Music.

Tree International: Excerpt from the song lyrics Okie From Muskogee by Merle Haggard and Roy Edward Burris. Copyright 1969 by Tree Publishing Co., Inc. Used by permission of the publisher. International copyright secured. All rights reserved.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Wright, Lawrence.

In the new world.

Bibliography: p.

1. United StatesCivilization1945

2. United statesSocial conditions19601980.

3. United StatesSocial conditions1980

4. Wright, Lawrence [date]. I. Title.

E169.12.W75 1987 973.92 87-45234

eISBN: 978-0-345-80296-5

Author photograph Matt Valentine

www.vintagebooks.com

Cover photo: The clock atop the Texas School Book Depository Building in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1964, flashes the exact time snipers bullets fired from the building mortally wounded President F. Kennedy one year ago. At 12:30 P.M., on Nov. 22, 1963 AP Photo

v3.1_c1

To my father and mother,

Don and Dorothy Wright

For there is a new world to be wona world of peace and good will, a world of hope and abundance; and I want America to lead the way to that new world.

JOHN F. KENNEDY

(July 4, 1960)

My friends, it is because we are on the side of right: it is because we are on Gods side: that America will meet this challenge and that we will build a better America at home and that that better America will lead the forces of freedom in building a new world.

RICHARD NIXON

(Last speech of the 1960 campaign)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book tells the story of a young American living an unremarkable life in the middle of the twentieth century, in a place rarely noticed by scholars or writers or journalistsuntil John F. Kennedy died there, and the world he inhabits suddenly becomes the subject of universal, microscopic, and scathing examination. It may seem strange, fifty years after the event, that such a moment could so define an age. There were other, greater events in the 1960snotably, the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam Warbut the Kennedy assassination seemed to have opened a door to the social turmoil that followed. It also posed a permanent unanswered question about the country we might have been, had the president chosen not to go to Dallas on that fateful day.

Twenty years after Kennedys death, I began an account of what it was like to be in Dallas at that time. I did not see my life as being extraordinary in any way, but it was in some respects exemplary. I represented a generationthe Baby Boomerswhose outsized presence has dominated American society from our conception in the exuberant postwar years, and no doubt will continue to do so until our final obituary is written. I was also a product of a vast migration to the Southwest, which would become the new political center of the United States, a region with different values, morals, and attitudes from what we resentfully called the Eastern Establishment.

My father was a pioneer in this new world. Like Kennedy, he was a minor hero in the Second World War, although in other respects they led utterly different lives. Kennedy came from wealth and privilege; Don Wright came from a desolate farm in Kansas, in the middle of the Dust Bowl. Instead of Harvard, my father had attended a teachers college in Oklahoma, sharing a bed with two other male students, and went on to law school at the state university, becoming the only member of his family to escape the narrow existence that broke the spirits of his other siblings, leading to bouts of alcoholism, abuse, and mental illness.

My fathers generation faced the challenges of the Depression and world war, and in the process they turned America into the most formidable economic, military, and political force in history. Naturally, they were concerned about the reliability of their heirs. We were far better off, better educated, and more sheltered from need than our parents had been. They had wanted to make the world a better place for their children, but having done so, they worried about the generation they had created, whom they saw as soft and privileged, as well as arrogant and ungratefulwhich, being young, we were. The damaging quarrel that erupted between my father and me was characteristic of the argument the two generations were having in households all across America.

The quarrel began with the war his generation gave mineVietnamwhere the first casualty was our standing as a noncolonial power with a special hold on universal moral values. There was also the stain of racism that has discolored our national honor since its beginning. The civil rights movement was the greatest social transformation in American history, and it marked another political divide between the generations. My parents werent racists, although they were informed by their own provincial backgrounds and were slow to see the need for profound reform. As a young reporter for the Race Relations Reporter in Nashville, Tennessee, I followed the progression of the movement from the streets to the courtrooms and the voting booths of Mississippi and Louisiana. Ive watched with pride as the movement passed into the state legislatures and city halls around the country, before finally arriving at the Oval Office. That is not to say that the struggle is over, but it will prevail.