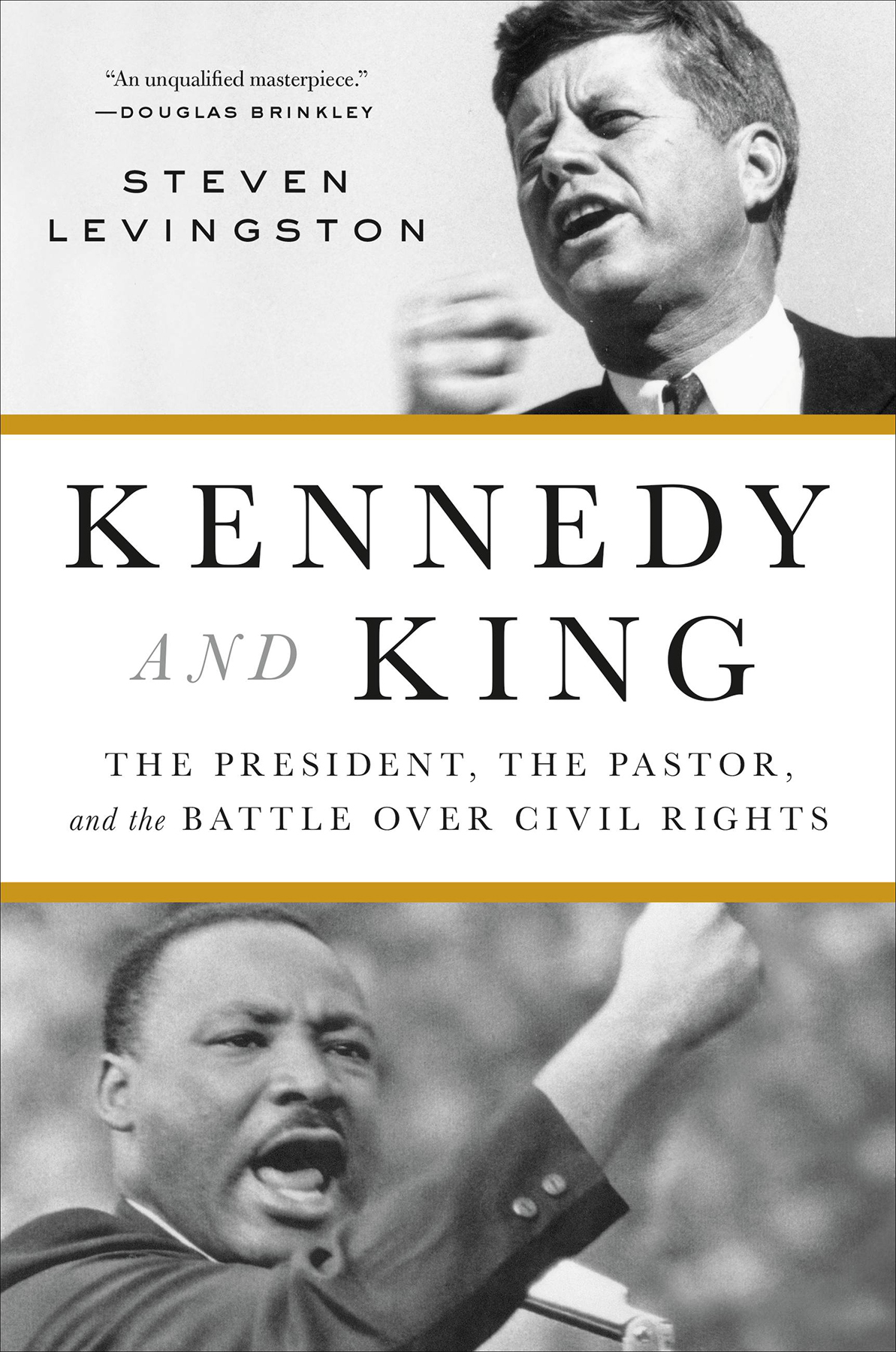

O N T UESDAY EVENING , June 11, 1963, President John F. Kennedy settled in behind his Oval Office desk, a pillow supporting his ailing back. Floodlights blazed, thick cables snaked across the floor, a bulky television camera stared at him. In minutes he was going live. Just three hours earlier, he had decided to speak to the nation. His speech had been hurriedly cobbled together, and was somewhat incomplete. But he knew what he wanted to say and, if necessary, hed ad lib it. Looking down at his text, the president scratched out a few words and wrote in his own. Setting down his pen, he was ready. Although he was not fully conscious of it, President Kennedy had been building up to this moment for two and a half years. A technician called out a thirty-second warning.

America was at a crossroads on civil rights. Protesters opposed to segregationsome as young as sixhad lately poured into the streets of Birmingham, Alabama, and were bullied by snarling police dogs and blasted off their feet by fire department water cannons. Demonstrations sprang up across the nation in solidarity. Earlier in the day, in Tuscaloosa, Governor George Wallace stood theatrically in the schoolhouse door to block the admission of two black students to the University of Alabama.

Just before 8 p.m., as the president put the finishing touches on his speech, Martin Luther King Jr. took a seat in front of his television in Atlanta, Georgia, joining millions of Americans coast to coast. Since Kennedys razor-thin victory in 1960, King had implored the president to commit fully to the cause of racial equality. In telegrams and phone calls to the White House, in television interviews and newspaper articles, in face-to-face meetings, and in fiery rhetoric from the pulpit, the pastor pressed the president to confront racist Southern politicians and end the indignity of segregation. But Kings pleas had been largely ignored.

In the Oval Office, the television cameras red light blinked on and President Kennedy went live. He began by chiding Governor Wallace for his puffed-up defiance in the schoolhouse door that afternoon; he expressed his regret that the Alabama National Guard had to be called out to enforce a court order to desegregate the states classrooms. But he was pleased by the outcome: that two qualified black students were now going to attend the University of Alabama.

The president reminded the nation that while Abraham Lincoln had freed the slaves a hundred years earlier, their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free. He said America faced a moral crisis over race, and he called on all citizens to change the way they treated each other. It was time, he said, for action in Congress. Having refused to challenge lawmakers on this explosive issue, he now promised legislation to ensure equal treatment for black Americans. At last President Kennedy had found his voiceand his courageon the most pressing domestic matter of the day: civil rights.

Watching in Atlanta, King leapt out of his chair. On the phone with friends, he wept. Hurriedly he shot off a telegram to the White House, calling the speech the clearest cry for black justice ever uttered by a president. It was a triumph not only for black Americans but for King himself. Although never claiming credit, King had played an instrumental role in Kennedys transformation. He had directed his civil rights campaigns at the White House, knowing no real change was possible without the moral leadership of the president. His oratory, his pitched street battles, and his repeated jailings forced a distant president to pay attention. As John Lewis, the veteran civil rights activist and long-serving U.S. congressman, put it: The very being, the very presence, of Martin Luther King Jr. pricked the conscience of John F. Kennedy.

In thirteen minutes on that June evening, Kennedy became the nations first civil rights president. Looking back, King marveled at his evolution. We saw two Kennedys, he explained, a Kennedy the first two years and another Kennedy emerging in 1963. The second Kennedy, in Kings view, was a man who not only saw the moral issues but who was now willing to stand up in a courageous manner for them.

* * *

The civil rights story of the early 1960s is a tale of sit-ins, street protests, massive arrests, police brutality, church bombings, and unsolved murders. It is also a tale of two menJohn F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.and their complicated relationship. Kennedy and King towered over the national landscape, and their interactions defined the early years of the civil rights era. While broad, forceful trends propel the trajectory of history, prominent personalities like Kennedy and King ultimately guide the course of human life. The nineteenth-century thinker Thomas Carlyle believed that great individuals, or heroes, shaped the worlds destiny. Historian Margaret MacMillan explains: Leaders have choices and the capacity to take history down one path rather than another.

Although Kennedy and King shared the historical stage, the two men inhabited vastly different worlds. One was a wealthy New England Irish Catholic, the other a black Southern Baptist preacher. Kennedy was leader of the free world, King spoke for Americas twenty million blacks. The men had little natural rapport. When they met face-to-face, their social styles clashed: Kennedy was cool and witty, King taut and high-minded. But they had much in common, too: Both men benefited from their oratorical brilliance and from the profound love of domineering fathers; and both knew the pangs of discriminationthe Kennedys as Irish Catholic immigrants in Protestant Boston, the King family as descendants of slaves.