CONTENTS

by Mark Winne

by David Hanson

The Neighborhood Garden

The Farm as Therapy

The Historic Farm

The Garden as Community

The Farm forProfit

Backyards of Bounty

The Education and Production Farm

The Nonprofit, For-Profit Farm

The Rooftop Farm

The Alternative Curriculum Farm

The Job Training Farm

The Peri-urban Farm

by Edwin Marty

FOREWORD

MARK WINNE

As a kid growing up in northern NewJersey, I acutely felt the tension between urban development and the fleetingremnants of a pastoral landscape. Living at the retreating edge of the GardenStates former agrarian glory, I often wondered how Mother Earth could survivethe onslaught of macadam, concrete, plastic, steel, and rubber. I wouldeventually find a kind of perverse solace in the hearty blades of grass andindefatigable dandelion shoots that muscled their way through the fissures inroadways and parking lots. They told me better than any science textbook couldthat no matter what abuse humankind may heap on our planet, nature will not onlysurvive but one day triumph.

Yet we dont need to wait (or, in bleakermoments, hope) for some kind of Armageddon to wash away our mess, the satisfyingand edifying stories told in Breaking ThroughConcrete make it abundantly clear that humanitys need to allownature to flourish may matter even more than natures will to survive. Urbanfarming, gardening, and growingor whatever you want to call the phenomenon thatis altering the definition of conventional food productionis catching on fasterthan veggie wraps. Turning over manicured sod at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue,removing rubble and covering old parking lots with compost in Rust Belt Detroit,and raising growing beds on Brooklyn rooftops the way a community used to raisebarns are the stories of the day.

Skeptics, of course, abound. Spokespersonsfor Big Farming and Big Food have turned their noses up at these so-called urbanaesthetes and utopian farmers whose acreage is so small that it can barelysupport a rototiller. But with a billion of the globes people hungry, a secondbillion undernourished, and another billion obese, conventional and industrialforms of agriculture have hardly earned bragging rights. Urban food productionmay not feed a hungry world, but as Breaking ThroughConcrete amply demonstrates, it can feed a hungry spirit and a hungerfor both nature and human connection. And as the world becomes less food secureevery day, growing food in unconventional places will be thought of no longer asa nicety, like a flower box of petunias slung from a brownstones windowsill,but as a necessity born out of the looming realization that there will be ninebillion of us to feed by 2050. At the very least, urban farming can be thoughtof as an insurance policy with a modest monthly premium, or as a hedge fund withno downside risk.

As a child of the sixties, my worldview wasshaped as much by the devastation of the moment as it was by a wild, fantasticalnotion of the future. While Joni Mitchell may have told us, They paved paradiseand put up a parking lot, Breaking ThroughConcrete reminds us that we can also rip up the parking lot andliberate paradise.

PREFACE

DAVID HANSON

Edwin Marty and I started talking abouta book on urban farms at the Garage Caf in the Southside neighborhood ofBirmingham, Alabama. It is one of those eccentric dives that seem to populatethe South more than any other region. The back courtyard is shaded by old treesthat force their way out of the uneven patio and stretch their twisted branchesover the chunky concrete tables and wobbly benches. Rooms filled with teeteringstacks of wrought-iron antiques and statuary only sometimes for sale are closedoff by sliding glass doors that look into the courtyard.

Its the kind of place where ideas hatch.Ive known Edwin for years because we both worked for the samemagazine-publishing group in town. Edwin eventually went full-time into JonesValley Urban Farm and urban agriculture consulting, and I began to followsmart-growth developments with the magazine I worked for at the time. We bothsaw the trends happening: new farmer visionaries planting their ideas inneighborhoods and towns around the country, and an emerging market of consumersseeking a connection to their food. And the scenes and the stories and thepeople were inspiring.

But we didnt see any publications thatcelebrated the new American urban farm movement. The buzz around urban farms isflourishing, as expected considering the increase in farmers markets, the trendof farm-to-plate restaurants, and the food-focused media in many cities. Butmany farms and food-garden projects around the country still exist in their ownlittle bubbles, and the large percentage of Americans who have recently come toappreciate the idea of organic seem unaware of not only the presence of urbanfarms in most American cities but also the discussion within the farm movementof what an urban farm is. And the urban farm ismany things.

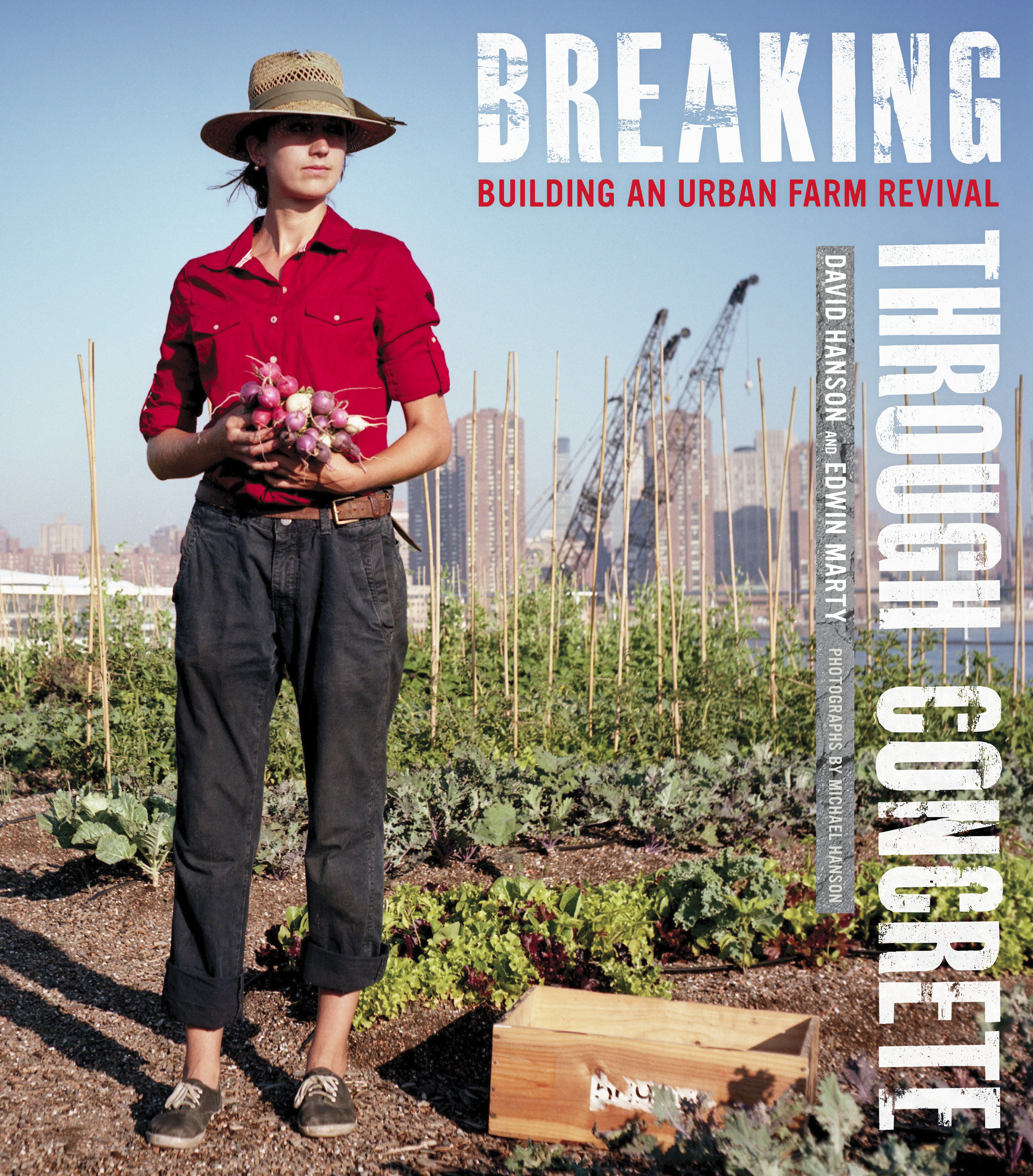

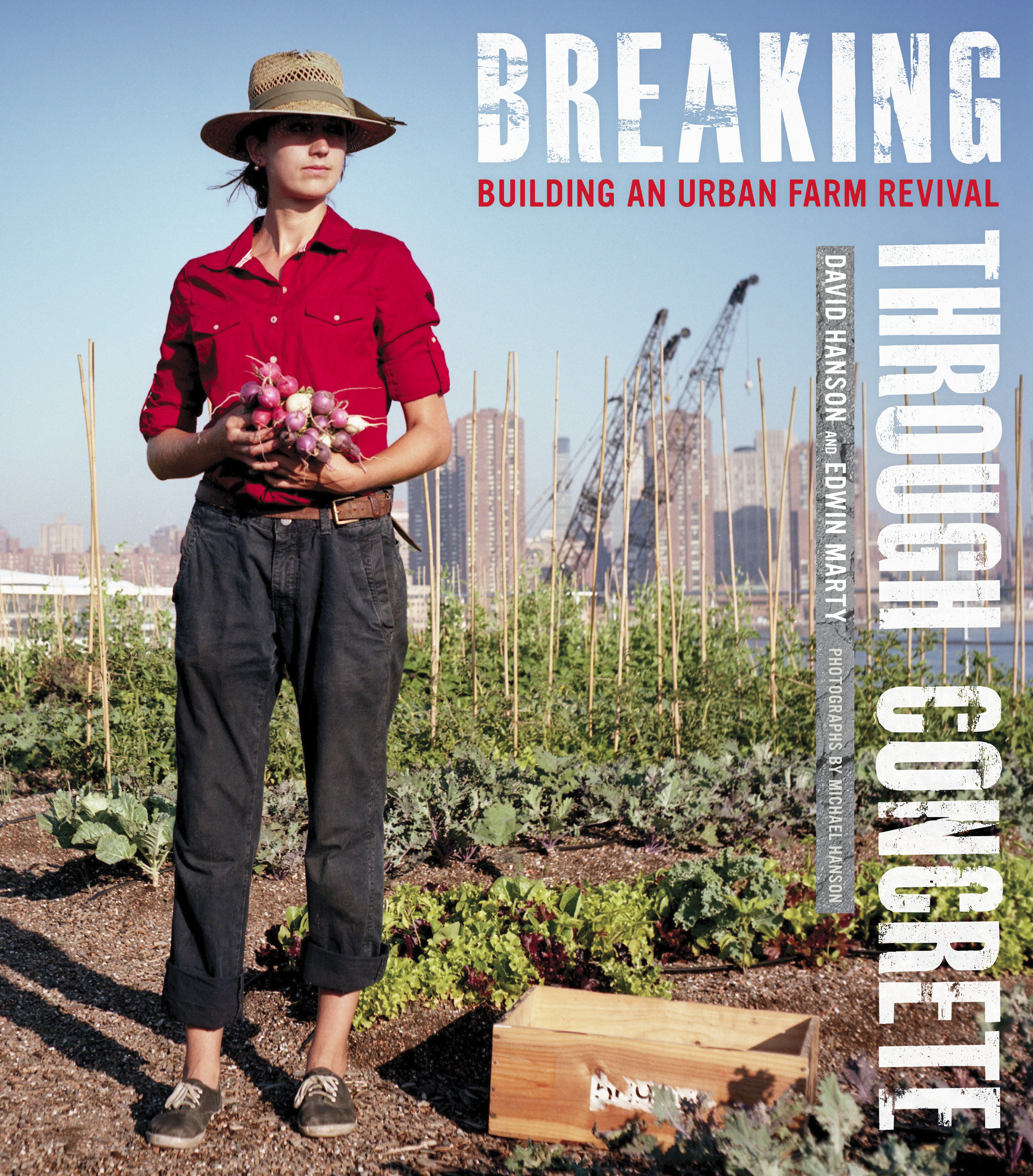

So, back in the Garage, we decided we shouldcollect the stories and images from a representative selection of American urbanfarms as they exist in 2010. We searched the country for the best examples ofthe diverse ways urban farms operate and benefit their communities. We put itall down in a big book proposal and the University of California Press bit.

Uh-oh. Now we actually had to make thishappen. This was January 2010. On May 19, 2010, my brother, photographer MichaelHanson; videographer and friend Charlie Hoxie; and I left Seattle, Washington,in a short Blue Bird school bus named Lewis Lewis. The remodeled interior sleptthree and had a kitchen and two work desks. The engine ran on diesel andrecycled vegetable oil. We had two months and over a dozen cities to visitbetween Seattle, New Orleans, Brooklyn, and Chicago.

The journey took us into a rich vein ofAmerican entrepreneurialism. The old spirit of opportunity and optimism wasbursting at the seams in the farms we encountered. Each stop along ourcounterclockwise cross-country ramble inspired us with new ideas and differentfaces speaking eloquently and passionately about helping their communities.

There might not be a better way to seeAmerica right now than via a short bus smoking fry grease. We connected withurban farmers, of course. But we also spent (too much) time with dieselmechanics, with cops in small-town Arkansas, and with biodiesel greasers sellingor giving away their salvaged fuel. In Vona, Colorado, while eating dinnerbesides Lewis Lewis and watching the setting sun light up a grain silo, we metthe families of large-scale agriculture. More than once, we were rousted fromsleep in the middle of the night and kicked out of mall parking lots. A schoolbus spray painted white and traveling at 55 miles per hour sparks the curiosityof many of the people it passes, and thats mostly a good thing.

Unfortunately, Lewis Lewis refused to budgefrom Birminghams Jones Valley Urban Farm, which was appropriate. You see, thebus was named after Edwins first employee, Lewis Nelson Lewis, a homeless manin Birmingham who began helping Edwin at the Southside garden. He worked hard,if sporadically, and Edwin eventually hired him. Lewis became a staple of anyfarm activity, and its not a stretch to say that Edwin and the farm were hislifeblood. Lewis Lewis passed away on April 20, 2009 . Its no wonder Lewis Lewis the Busdid not want to leave his farm. We continued on our route up the East Coast in awhite minivan, though we undoubtedly lost a spirit of adventure.