A PEOPLES GUIDE TO

LOS ANGELES

A PEOPLES GUIDE TO

LOS ANGELES

Laura Pulido Laura Barraclough Wendy Cheng

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

Every effort has been made to identify the rightful copyright holders of material not specifically commissioned for use in this publication and to secure permission, where applicable, for reuse of all such material. Credit, if and as available, has been provided for all borrowed material either on-page, on the copyright page, or in a credit section of the book. Errors or omissions in credit citations or failure to obtain permission if required by copyright law have been either unavoidable or unintentional. The authors and publisher welcome any information that would allow them to correct future reprints.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2012 by The Regents of the University of California

Photos by Wendy Cheng unless credited otherwise.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pulido, Laura.

A peoples guide to Los Angeles / Laura Pulido, Laura Barraclough, Wendy Cheng. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-27081-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Los Angeles (Calif.)Guidebooks. 2. Los Angeles Region (Calif.)Guidebooks. 3. Los Angeles (Calif.)Social conditions. 4. Los Angeles (Calif.)History. I. Barraclough, Laura R. II. Cheng, Wendy, 1977 III. Title.

F869.L83P85 2012

979.4'94dc23 2011039098

Manufactured in the United States of America

21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 2002) (Permanence of Paper).

To the people of Los Angeles: past, present,

and futureespecially those in the struggle,

those who teach, and those who learn;

and to Leela, Amani, and Alessandro

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the

generous support of the Lisa See Endowment Fund

in Southern California History and Culture of the

University of California Press Foundation.

Contents

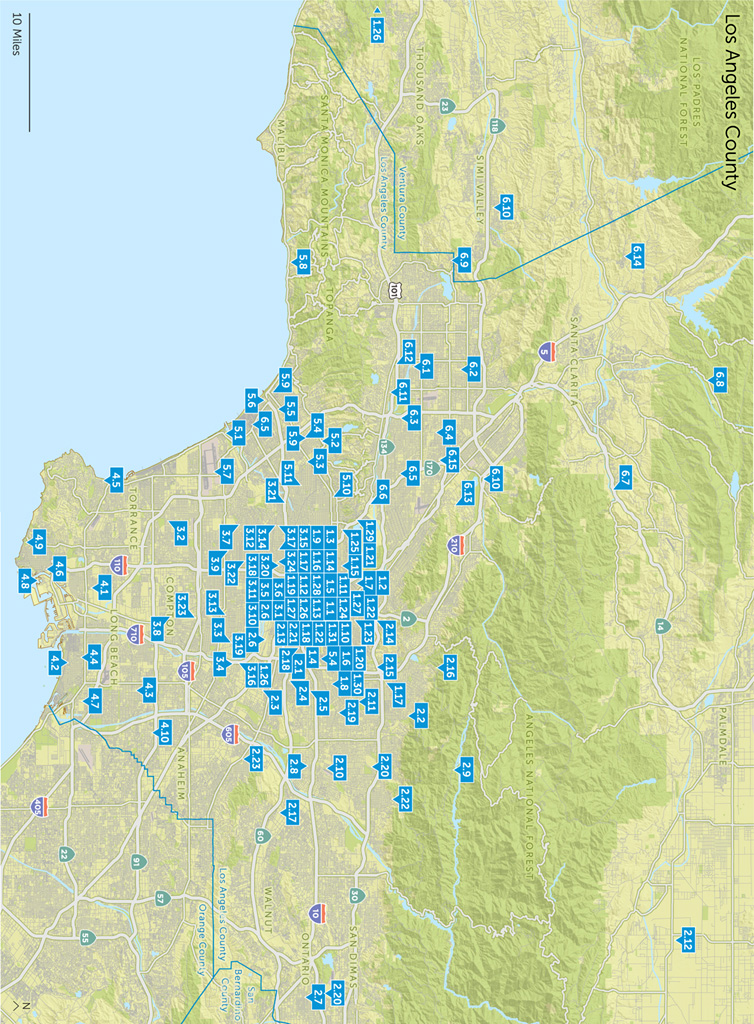

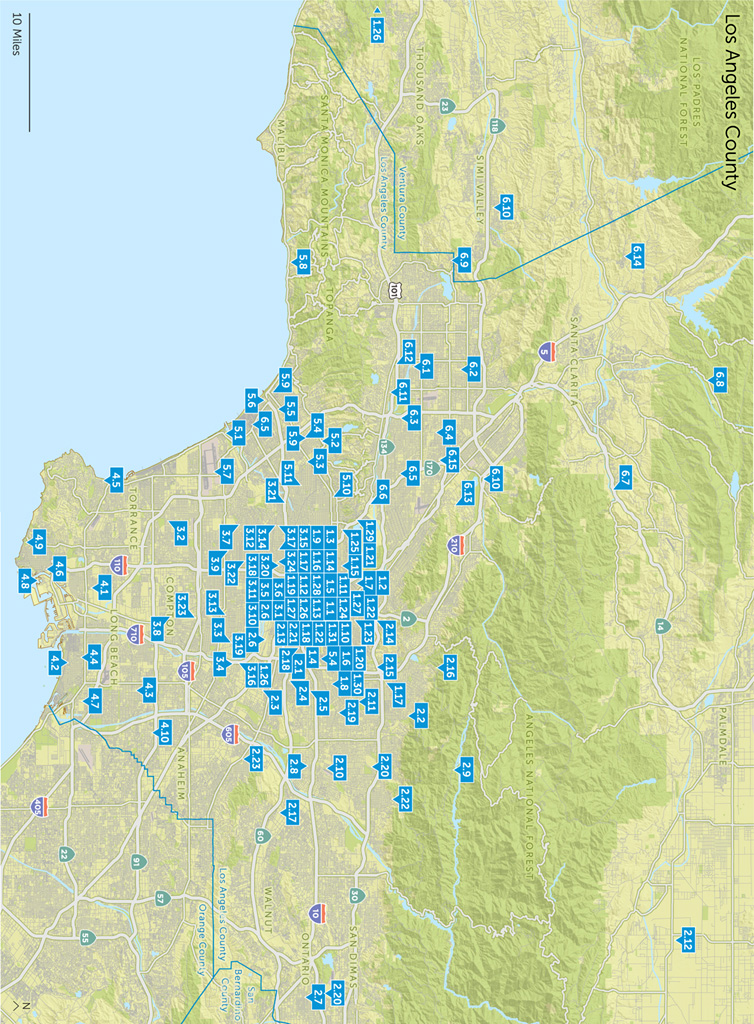

Maps

Paved lot at 4115 South Central Ave., 2009.

An Introduction to A Peoples Guide to Los Angeles

In the middle of the day, the sun shines indifferently on the paved lot at 4115 South Central Avenue. The north side of the long, narrow lot at this address faces a two-story strip mall painted yellow. Hand-painted lettering and vinyl banners slung over the railings advertise photo services, seven-dollar haircuts, and toda clase de herramientas (all kinds of tools). The south side of the lot abuts a faded brick building with frutas y verduras [fruits and vegetables], 99 cents & up hand-painted on the wall. A row of small, irregular metal squares runs along the topfasteners of support beams meant to prevent the walls from collapsing in the event of an earthquake. The squares testify to the buildings age, since this type of reinforcement was often used for brick buildings built before 1933; this is an old neighborhood, and these buildings have been around for a while. This brick building, currently home to a corner grocery store and a hardware store, once had a twin, which filled the now empty lot. In that lost building, in the late 1960s, the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP) made its headquarters. But on one fateful morning in December 1969, in a predawn raid that turned into a four-hour gun battle, hundreds of Los Angeles police officers fired thousands of rounds into the building, used a battering ram and helicopter, and trashed the inside, causing the roof of the building to cave in. Six people were injured and eleven Panthers were arrested, resulting in the retreat of party members to Oakland and the eventual demise of the Southern California chapter. Today on this stretch of Central Avenue, a man lifts the receiver of the pay phone in front of the market, replaces it, and walks away. Cars pass, stopping briefly in traffic and then moving on, in a constant stream. Three men rest on repurposed office chairs and a worn couch in the empty lot, enjoying an afternoon nap. Someone has planted a triangular patch of roses in the raised curb of a parking lot divider. The Panthers, and the building in which they did their work, are long gone.

Less than a mile to the east of the former BPP headquarters, an immense field filled with nothing but weeds and dirt and enclosed by chain-link fence affords an open view of the high-rises of downtown Los Angeles. If you look hard, you might find a few nopal plantsevidence that, not long ago, this was the site of the South Central Farm, the largest urban farm in the nation, and before that, it was the site of a successful community-led struggle to prevent the building of a toxic incinerator. But if you dont look closely or know these histories, this is just another ugly, abandoned industrial lot in South L.A.

In a park five miles farther east, teenagers bounce a basketball back and forth. On this weekday, the swing sets and slides of the modest playground are empty and the dirt baseball field goes unused. There is no trace of the footsteps and chants of the tens of thousands of people who filled this park on a hot day in August 1970 to protest the Vietnam War. The Chicano Moratorium, as it is known, was the largest antiwar action on the part of any ethnic community in the United States. Nor would you know that the tiny clothing store on nearby Whittier Boulevard was once a caf where the renowned Mexican American journalist Rubn Salazar was shot and killed by an L.A. sheriffs deputy during his coverage of the event, and that that is why the parkformerly known as Laguna Parkhas been named Ruben Salazar Park, in his honor.

Los Angeles is filled with ghostsnot only of people, but also of places and buildings and the ordinary and extraordinary moments and events that once filled them. There are many such places throughout the region; still others are being created while you read this. This book is a guide to such landscapes, moments, and events. Taking the form of a tourist guidebook, it both celebrates the victories occasionally won through popular struggles and mourns those struggles that have been lost.

A Peoples Guide to Los Angeles is a deliberate political disruption of the way Los Angeles is commonly known and experienced. A guidebook may seem an unusual or unlikely political intervention, but as representations of both history and geography, guidebooks play a critical role in reinforcing inequality and relations of power. Guidebooks select sites, put them on a map, and interpret them in terms of their historical and contemporary significance. All such representations are inherently political, because they highlight some perspectives while overlooking others. Struggles over who and what counts as historic and worthy of a visit involve decisions about who belongs and who doesnt, who is worth remembering and who can be forgotten, who we have been and who we are becoming. Since all historic processes occur somewhere, these questions inherently involve geographic priorities, biases, and exclusions, as some places are celebrated, others are de-emphasized, and still others are literally left off the map. Thus, while not usually thought of as political, guidebooks contribute to inequality in places like Los Angeles, not only by directing tourist and investment dollars toward some places and not others, but also by socializing visitors and locals alike about who and what is valuable, andby implicationwho and what is not.