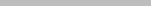

THE

WORLD

UNTIL

YESTERDAY

ALSO BY JARED DIAMOND

Collapse

Guns, Germs, and Steel

Why Is Sex Fun?

The Third Chimpanzee

JARED DIAMOND

THE

WORLD

UNTIL

YESTERDAY

WHAT CAN WE LEARN

FROM TRADITIONAL SOCIETIES?

VIKING

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North 2193, South Africa

Penguin China, B7 Jaiming Center, 27 East Third Ring Road North, Chaoyang District,

Beijing 100020, China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2012 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright Jared Diamond, 2012

All rights reserved

Photograph credits appear on .

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Diamond, Jared M.

The world until yesterday : what can we learn from traditional societies? / Jared Diamond.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-1-101-60600-1

1. Dani (New Guinean people)History. 2. Dani (New Guinean people)Social life and customs. 3. Dani (New Guinean people)Cultural assimilation. 4. Social evolutionPapua New Guinea. 5. Social changePapua New Guinea. 6. Papua New GuineaSocial life and customs. I. Title.

DU744.35.D32D53 2013

305.89912dc23

2012018386

Designed by Nancy Resnick

Maps by Matt Zebrowski

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

To

Meg Taylor,

in appreciation for decades

of your friendship,

and of sharing your insights into our two worlds

Contents

List of Tables and Figures

| Locations of 39 societies that will be discussed frequently in this book |

| Objects traded by some traditional societies |

| Membership of two warring Dani alliances |

| Causes of accidental death and injury |

| Traditional food storage around the world |

| Some proposed definitions of religion |

| Examples of supernatural beliefs confined to particular religions |

| Religions functions changing through time |

| Prevalences of Type-2 diabetes around the world |

| Examples of gluttony when food is abundantly available |

PROLOGUE

At the Airport

An airport scene  Why study traditional societies?

Why study traditional societies?  States

States  Types of traditional societies

Types of traditional societies  Approaches, causes, and sources

Approaches, causes, and sources  A small book about a big subject

A small book about a big subject  Plan of the book

Plan of the book

An airport scene

April 30, 2006, 7:00 A.M . Im in an airports check-in hall, gripping my baggage cart while being jostled by a crowd of other people also checking in for that mornings first flights. The scene is familiar: hundreds of travelers carrying suitcases, boxes, backpacks, and babies, forming parallel lines approaching a long counter, behind which stand uniformed airline employees at their computers. Other uniformed people are scattered among the crowd: pilots and stewardesses, baggage screeners, and two policemen swamped by the crowd and standing with nothing to do except to be visible. The screeners are X-raying luggage, airline employees tag the bags, and baggage handlers put the bags onto a conveyor belt carrying them off, hopefully to end up in the appropriate airplanes. Along the wall opposite the check-in counter are shops selling newspapers and fast food. Still other objects around me are the usual wall clocks, telephones, ATMs, escalators to the upper level, and of course airplanes on the runway visible through the terminal windows.

The airline clerks are moving their fingers over computer keyboards and looking at screens, punctuated by printing credit-card receipts at credit-card terminals. The crowd exhibits the usual mixture of good humor, patience, exasperation, respectful waiting on line, and greeting friends. When I reach the head of my line, I show a piece of paper (my flight itinerary) to someone Ive never seen before and will probably never see again (a check-in clerk). She in turn hands me a piece of paper giving me permission to fly hundreds of miles to a place that Ive never visited before, and whose inhabitants dont know me but will nevertheless tolerate my arrival.

To travelers from the U.S., Europe, or Asia, the first feature that would strike them as distinctive about this otherwise familiar scene is that all the people in the hall except myself and a few other tourists are New Guineans. Other differences that would be noted by overseas travelers are that the national flag over the counter is the black, red, and gold flag of the nation of Papua New Guinea, displaying a bird of paradise and the constellation of the Southern Cross; the counter airline signs dont say American Airlines or British Airways but Air Niugini; and the names of the flight destinations on the screens have an exotic ring: Wapenamanda, Goroka, Kikori, Kundiawa, and Wewak.

The airport at which I was checking in that morning was that of Port Moresby, capital of Papua New Guinea. To anyone with a sense of New Guineas historyincluding me, who first came to Papua New Guinea in 1964 when it was still administered by Australiathe scene was at once familiar, astonishing, and moving. I found myself mentally comparing the scene with the photographs taken by the first Australians to enter and discover New Guineas Highlands in 1931, teeming with a million New Guinea villagers still then using stone tools. In those photographs the Highlanders, who had been living for millennia in relative isolation with limited knowledge of an outside world, stare in horror at their first sight of Europeans (). I looked at the faces of those New Guinea passengers, counter clerks, and pilots at Port Moresby airport in 2006, and I saw in them the faces of the New Guineans photographed in 1931. The people standing around me in the airport were of course not the same individuals of the 1931 photographs, but their faces were similar, and some of them may have been their children and grandchildren.

Next page

Why study traditional societies?

Why study traditional societies?