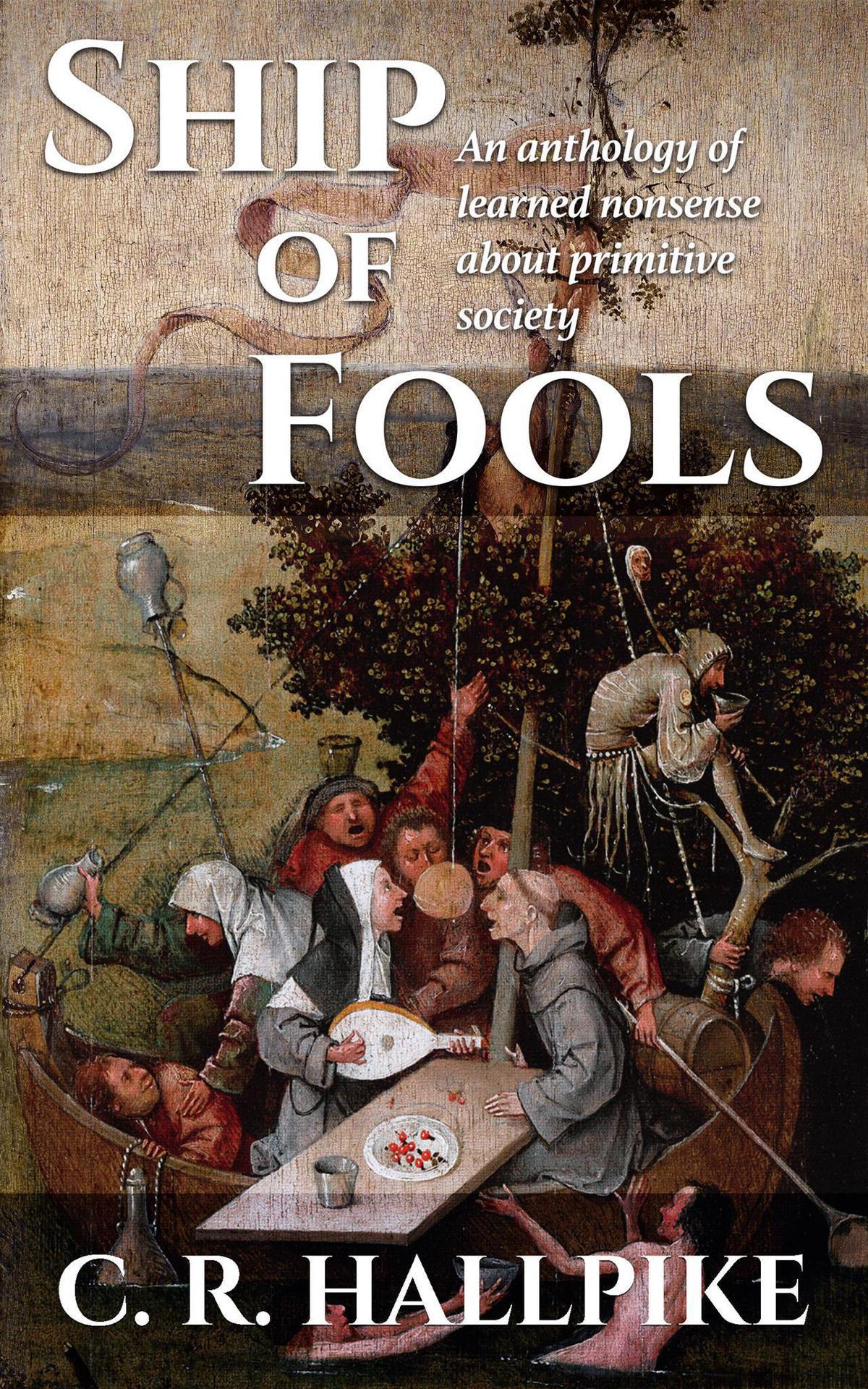

Ship of Fools

An anthology of learned nonsense

about primitive human societies

C. R. Hallpike

Copyright

Ship of Fools: An anthology of learned nonsense about primitive human societies

C. R. Hallpike

Castalia House

Kouvola, Finland

www.castaliahouse.com

This book or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwisewithout prior written permission of the publisher, except as provided by Finnish copyright law.

Copyright 2018 by C. R. Hallpike

All rights reserved

Version: 002

Contents

The crew are all quarrelling with each other about how to navigate the ship, each thinking he ought to be at the helm; they know no navigation and cannot say that anyone ever taught it them, or that they spent any time studying it; indeed they say it cant be taught and are ready to murder anyone who says it can. They spend all their time milling round the captain and trying to get him to give them the wheel. They have no idea that the true navigator must study the seasons of the year, the sky, the stars, the winds and other professional subjects, if he is to be really fit to control a ship.

Plato, The Republic , Bk. VI, Tr. H.D.P. Lee

Preface

I spent my first ten or so years as an anthropologist either living with mountain tribes in Ethiopia and Papua New Guinea or writing up my research for publication. These more primitive types of society are small-scale, face-to-face, without writing, money, or the state, organized on the basis of kinship, age, and gender, and with subsistence economies. As such they are very different from our own modern industrialised societies and it takes a good deal of study to understand how they work. But since all our ancestors used to live like this, understanding them is essential to understanding the human race itself, especially when speculating about our prehistoric ancestors in East Africa. Unfortunately a variety of journalists and science writers, historians, linguists, biologists, and especially evolutionary psychologists think they are qualified to write about primitive societies without knowing much about them, or, even worse, think that a political agenda justifies them in falsifying the record. The result in many cases has resembled a Ship of Fools, True Believers in some pet ideology like extreme neo-Darwinism, or social justice, or some will o the wisp of their own imaginations, and many of their speculations have about as much scientific credibility as The Flintstones. So the various critical studies in this little book are offered as a sort of bouquet or anthology of nonsense about primitive man, and I only hope my readers derive as much entertainment from them as I have had in writing them.

C.R.H.

Shipton Moyne

Gloucestershire

August 2018

Chapter I: Talking nonsense about early Man

1. What primitive societies are actually like

Before joining the Ship of Fools I thought it might be useful if I began with a rough guide to what primitive societies are like.

The most powerful impact of primitive society on the anthropologist is what I can only call the sheer immediacy and intimacy of the physical world, even in comparison with rural life in Europe or North America. In our WEIRD culture (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic), we experience the physical world to a great extent indirectly through our technology. So instead of walking we encounter the countryside through our cars, we talk to family, friends and neighbours over the telephone, and when we want water we turn on a tap, which brings it from some fairly distant part of the country by a huge system of reservoirs, pumping stations and pipes. In primitive societies, however, someone, almost invariably a woman, has to go and fetch it themselves from a water-hole, or stream, or well, in a bamboo or gourd container, or perhaps in a clay pot and carry it wearily home, sometimes several times a day. (Even in our own society just within living memory the village women would congregate at the pump or well on the green to get their water.)

In the primitive world everything is made by the people themselves, not out of metals and plastic in remote factories in other countries but out of familiar local materialswood, plants to use for thatching, thread, baskets, gourd or bamboo containers, stones for building and tools, and animal products like hide, sinew, and bone. The primitive world is also very small and human-sized. There are no great cities or gigantic multi-storey concrete buildings, just villages of small huts thatched with grass or palm leaves, the roof held up by wooden posts and maybe some wattle and daub to keep the draughts out, and with no furniture like tables, chairs and beds, let alone anything comfortable like sofas and armchairs. Just the bare ground to sleep on, except for a cowskin or some leaves, and nothing to sit on either, except perhaps for some stones or a piece of wood, and with no tables to put anything on. People grow the food they eat, probably very limited in variety, in the gardens and fields they own, and bring it home, usually on the womens backs, though in some societies there may be donkeys or other beasts of burden.

So life is extremely hard, and the food is usually dreadful. Members of our intelligentsia who chatter about the joys of this kind of life would probably have to be medically evacuated after a few weeks if they actually had to live with them under their traditional conditions of existence. The basic Konso meal, for example, mainly consisted of boiled sorghum dough and tree leaves, eaten three times a day, and sorghum is an unappetising cereal that is regarded by northern Ethiopians as t only for cattle. Chaqa , the beer made from it, is a sour alcoholic grain soup, usually served hot, which compares unfavourably with Ethiopian tej (honey wine) or beer made from barley. While Konso coffee is excellent, traditionally it was not drunk but the beans were roasted and eaten on ritual occasions, and honey was not used to make a drink either. Milk, if available, is drunk only by children, and butter, which is very expensive, is used more as a cosmetic than as an item of diet. Meat, to be sure, is sold in the markets as a luxury, but there is a notable absence in Konso of the spices which elsewhere in Ethiopia are used to produce a range of appetising dishes. Chickens were kept in the traditional society, but only for their feathers, since it was forbidden to eat any kinds of bird or their eggs.

The Tauade of Papua New Guinea grew sweet-potatoes, which are a good deal tastier than sorghum, and much easier to prepare, as well as yams and taro, with pork and smoked pandanus nuts as treats. But since meat in farming societies is a luxury, people are none too fussy about its quality. Garide, my Konso cook, and I had been up to the market one day to buy some meat and had brought it back in a plastic bag. In the hot season in Africa this is not a good idea, and when we came to open it some hours later the stench was appalling. A man happened to be passing the doorway of my house, however, and was very keen to buy it for the small sum we were asking and snapped up his bargain with alacrity. In Papua New Guinea the people are even less fastidious about their pork when it is stinking, even cutting it up under water when the smell is too bad. And yes, sometimes they died from it. Biologists often tell us that we are protected by the vomiting reflex from eating meat that has begun to smell as it goes bad, but no one seems to have told primitive peoples about this.

![C.R. Hallpike - On Primitive Society and other forbidden topics [notes fixed]](/uploads/posts/book/62486/thumbs/c-r-hallpike-on-primitive-society-and-other.jpg)