Also by Michael Burleigh

The Racial State: Germany 193345

Death and Deliverance

Germany Turns Eastward

The Third Reich: A New History

Earthly Powers

Sacred Causes

Blood and Rage

Moral Combat

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

Copyright Michael Burleigh, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

First published in Great Britain by Macmillan, an imprint of Pan Macmillan

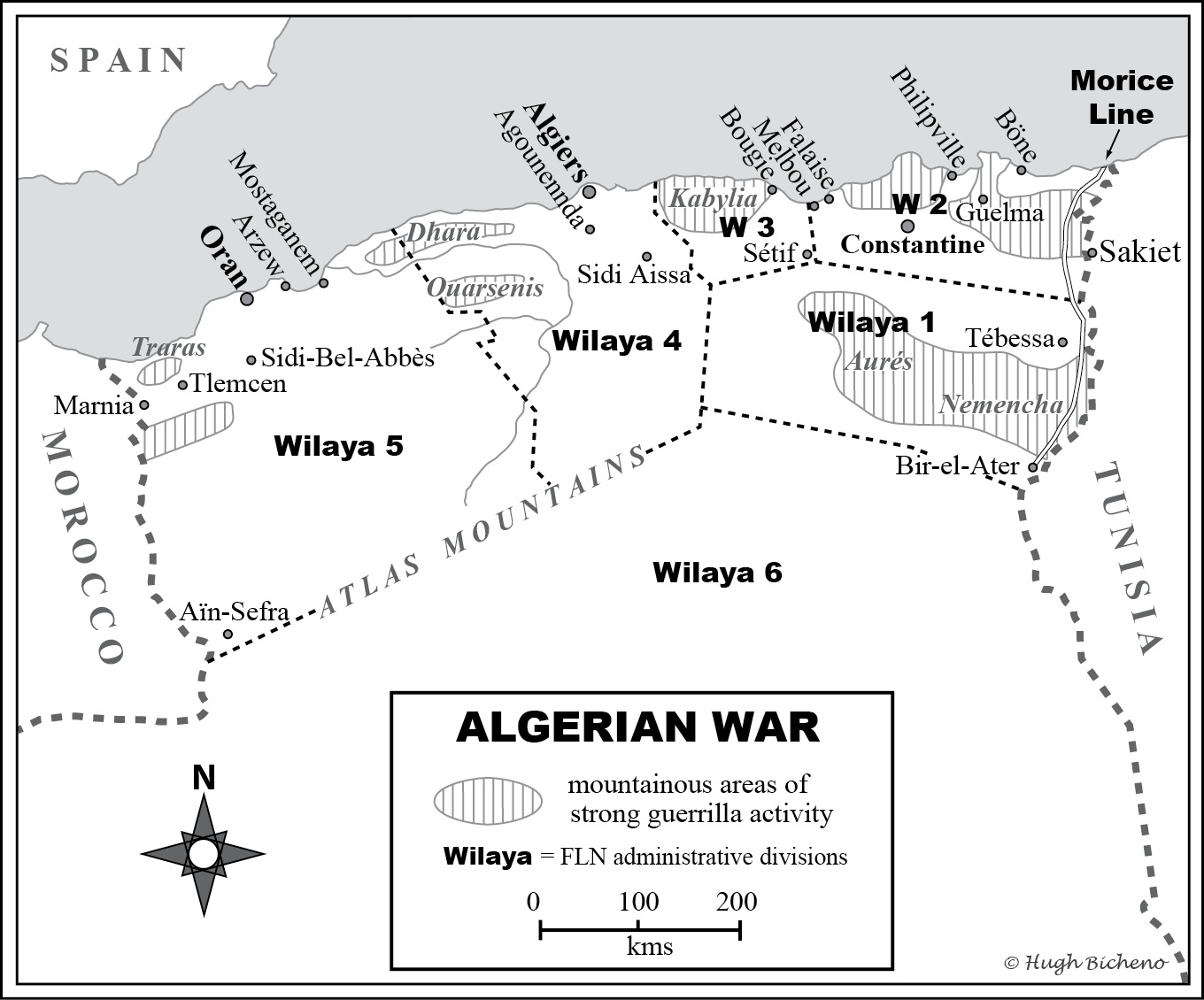

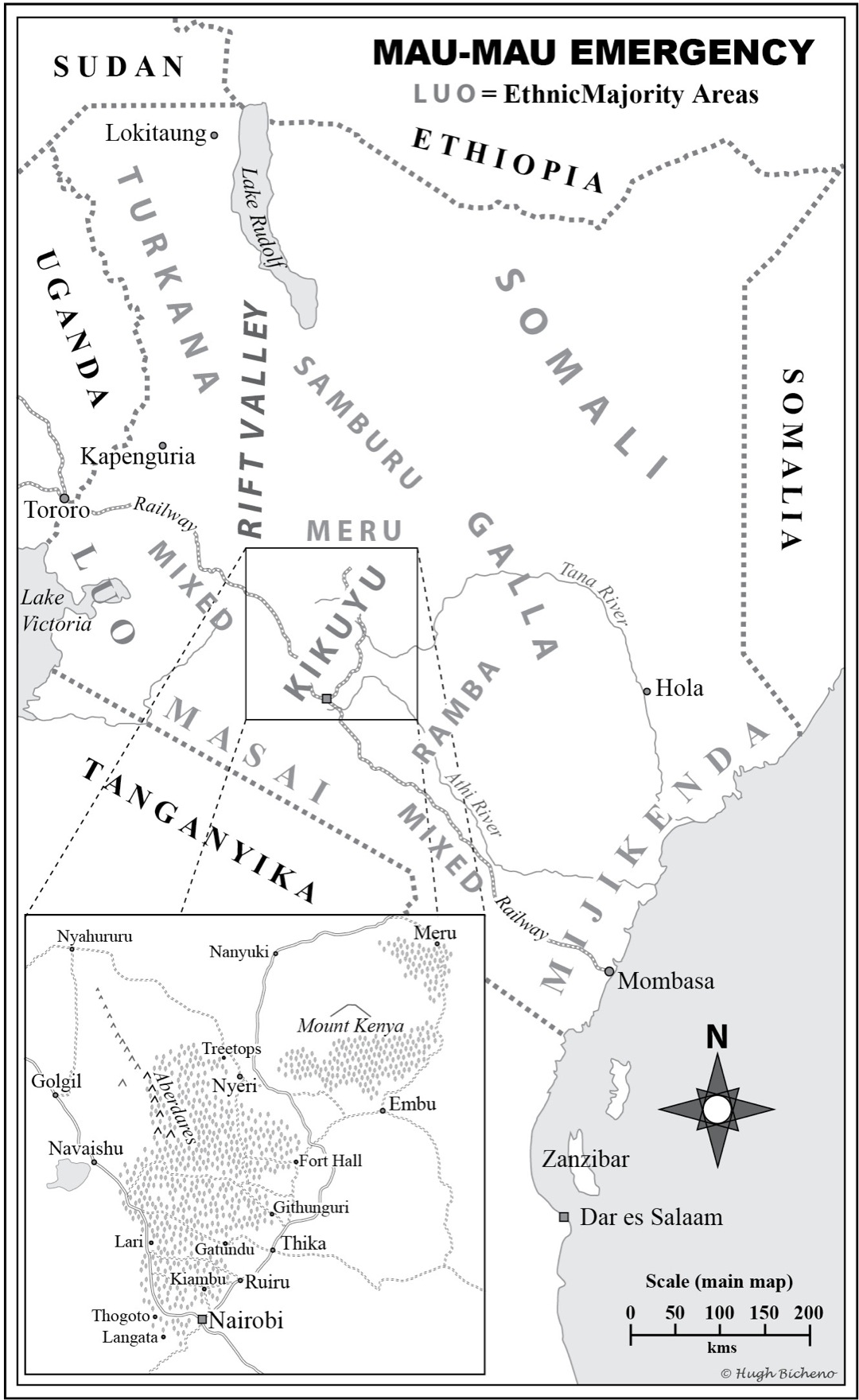

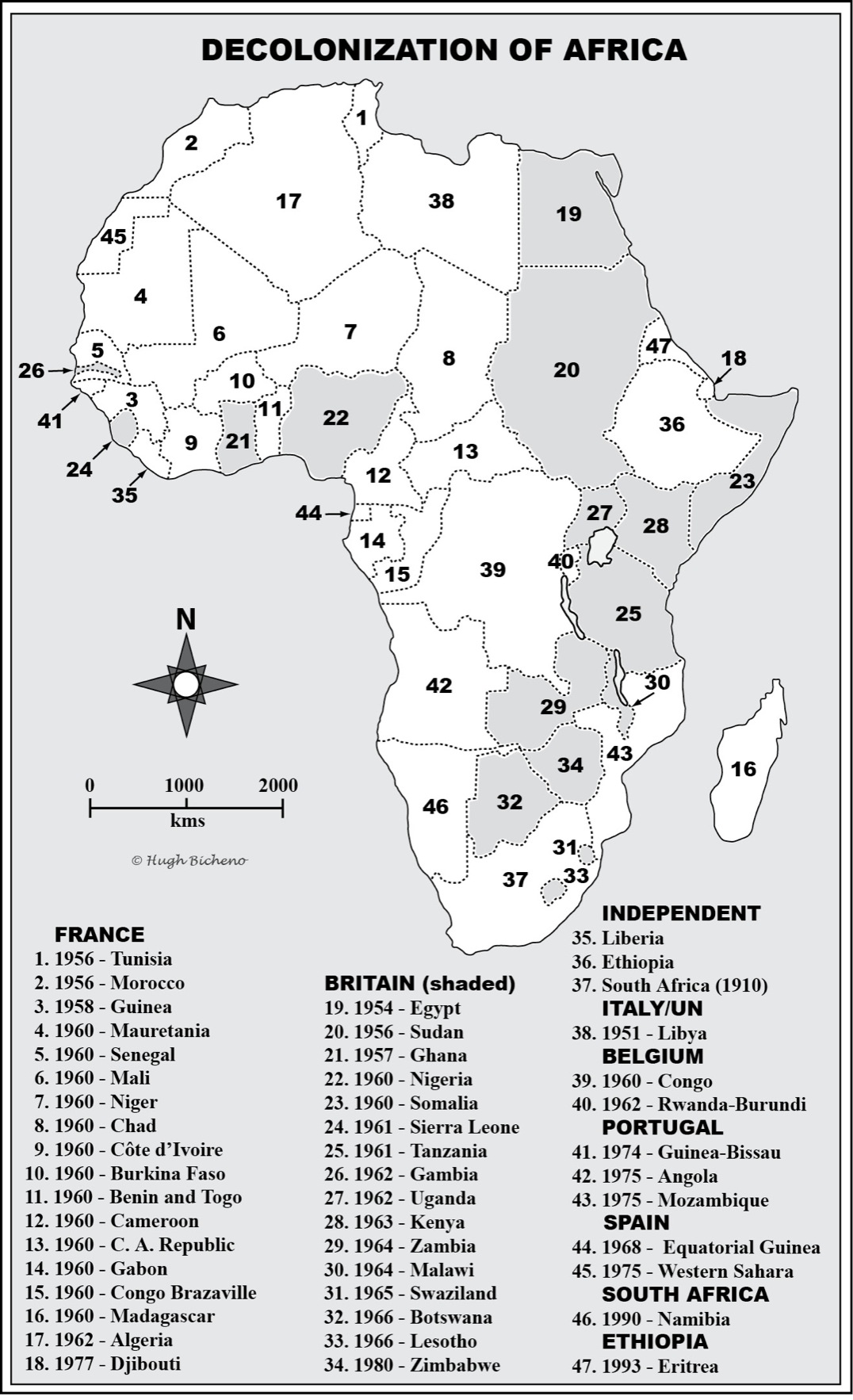

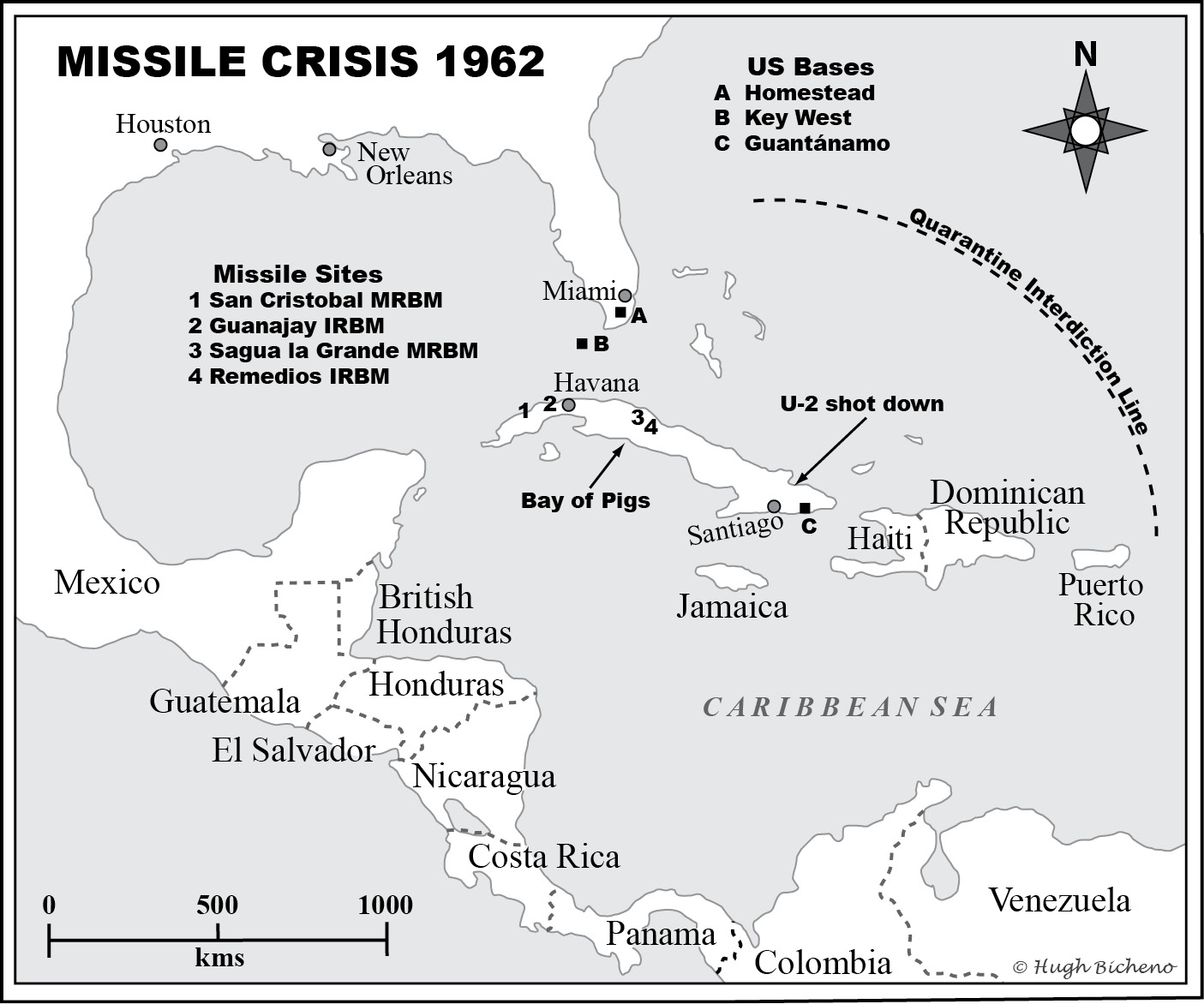

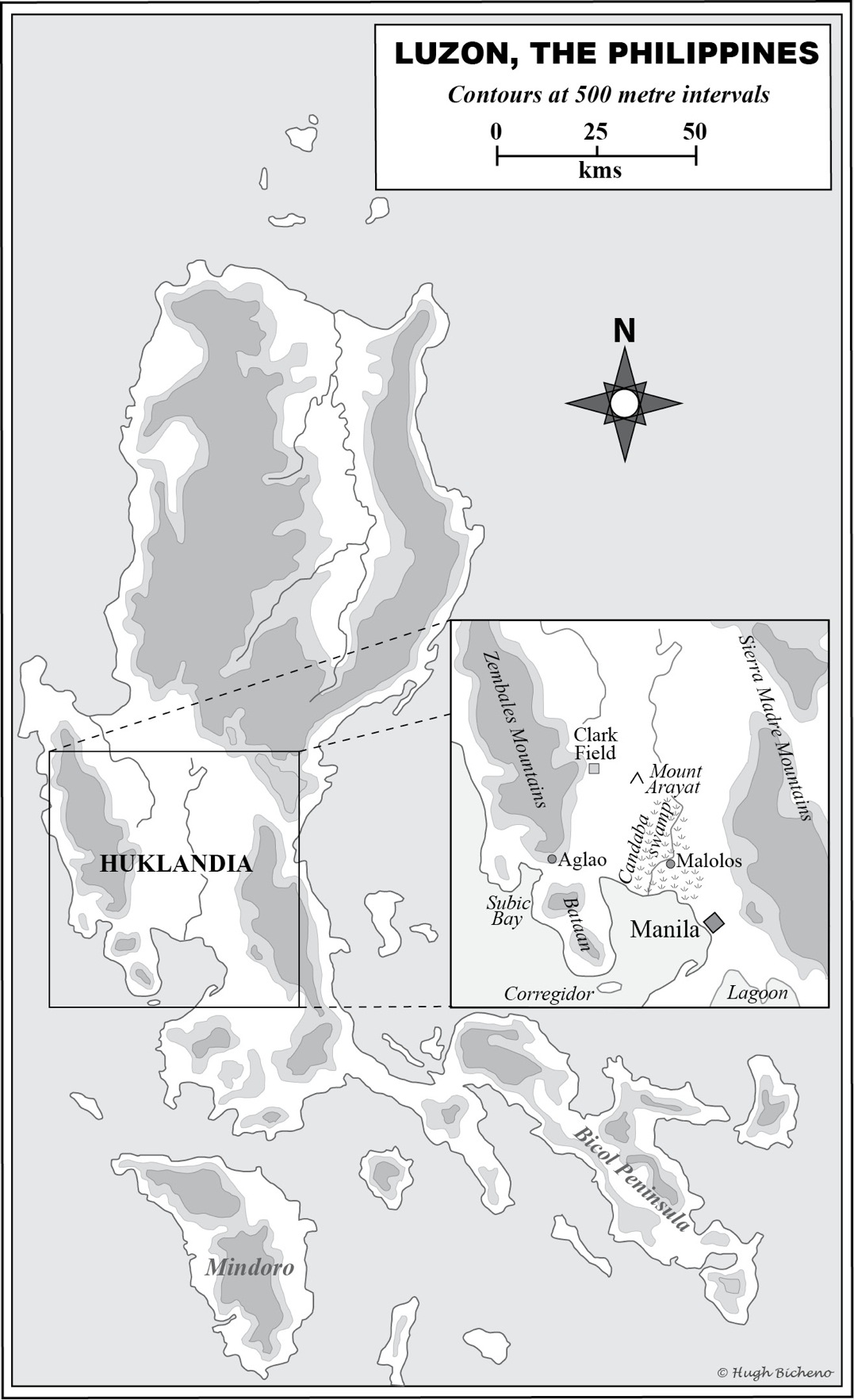

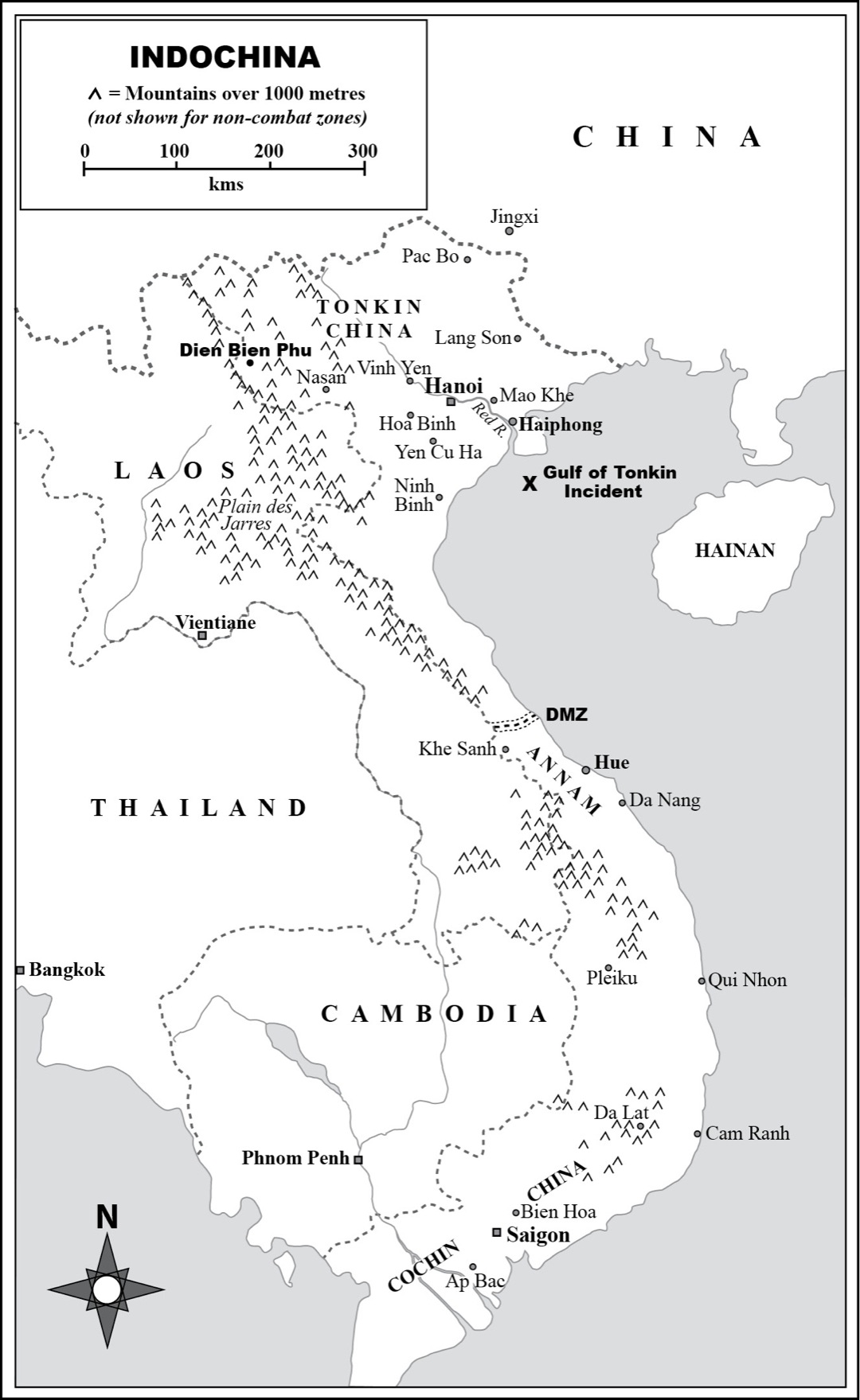

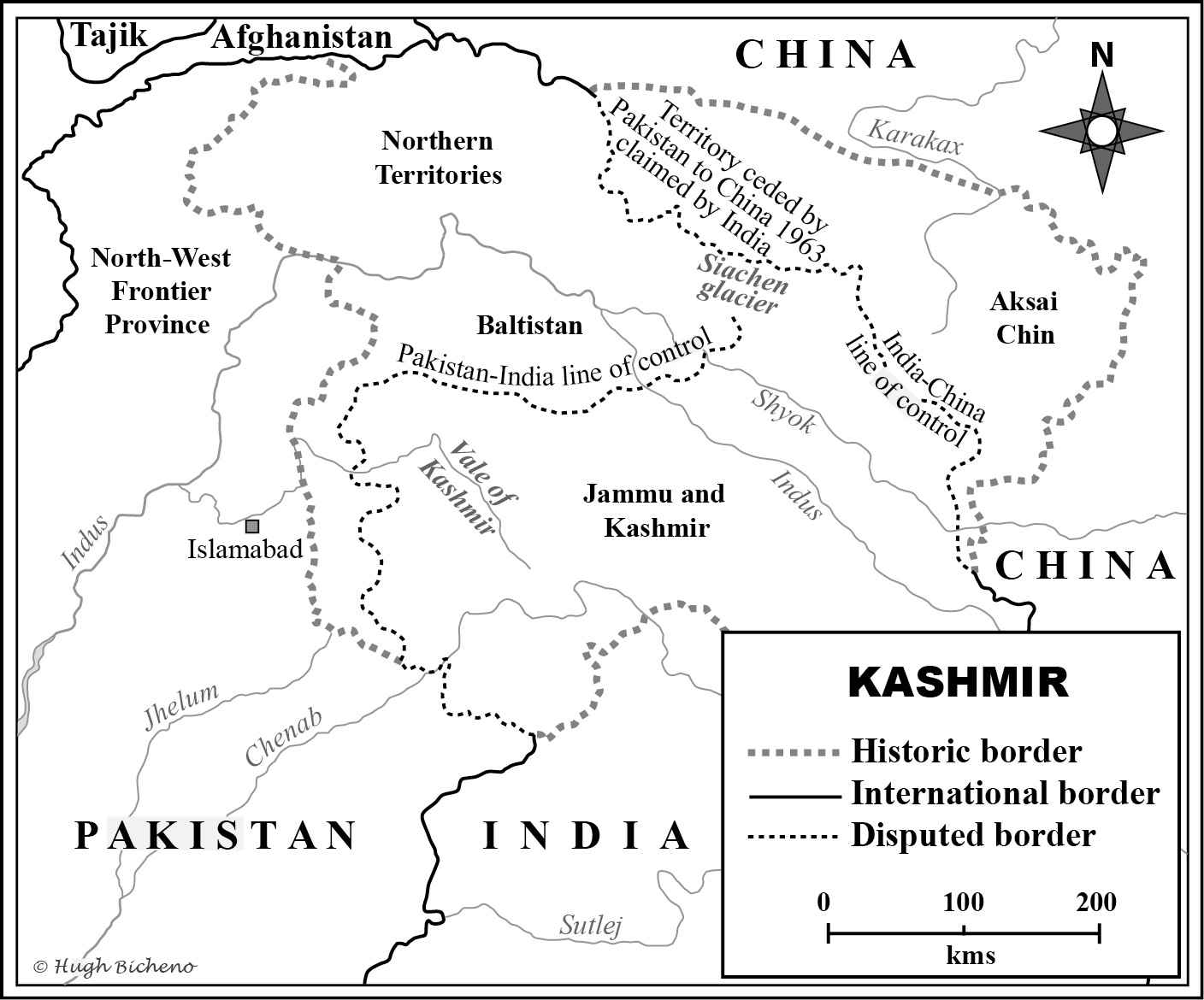

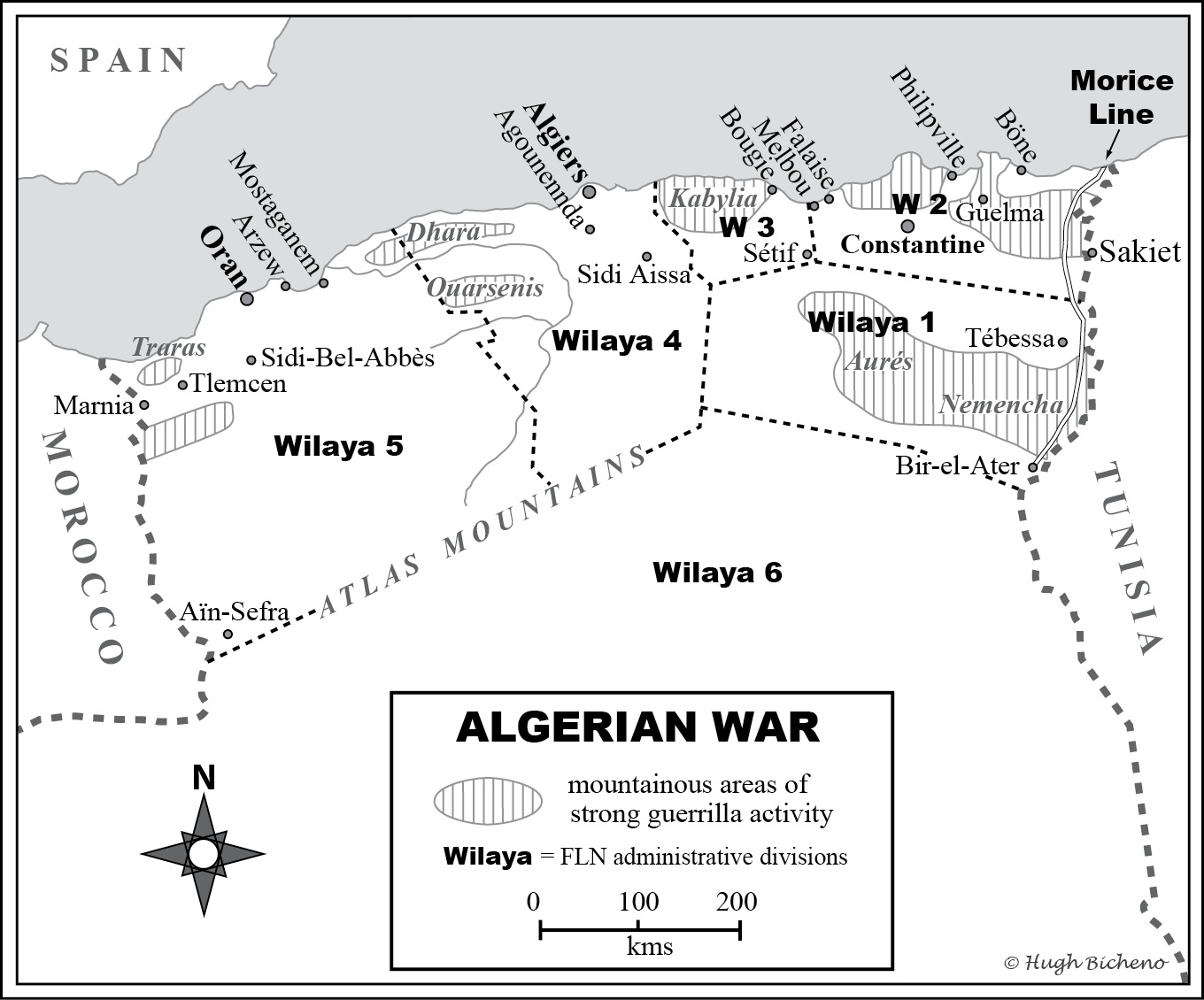

Map illustrations by Hugo Bicheno

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burleigh, Michael, 1955

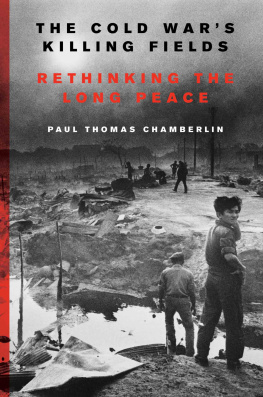

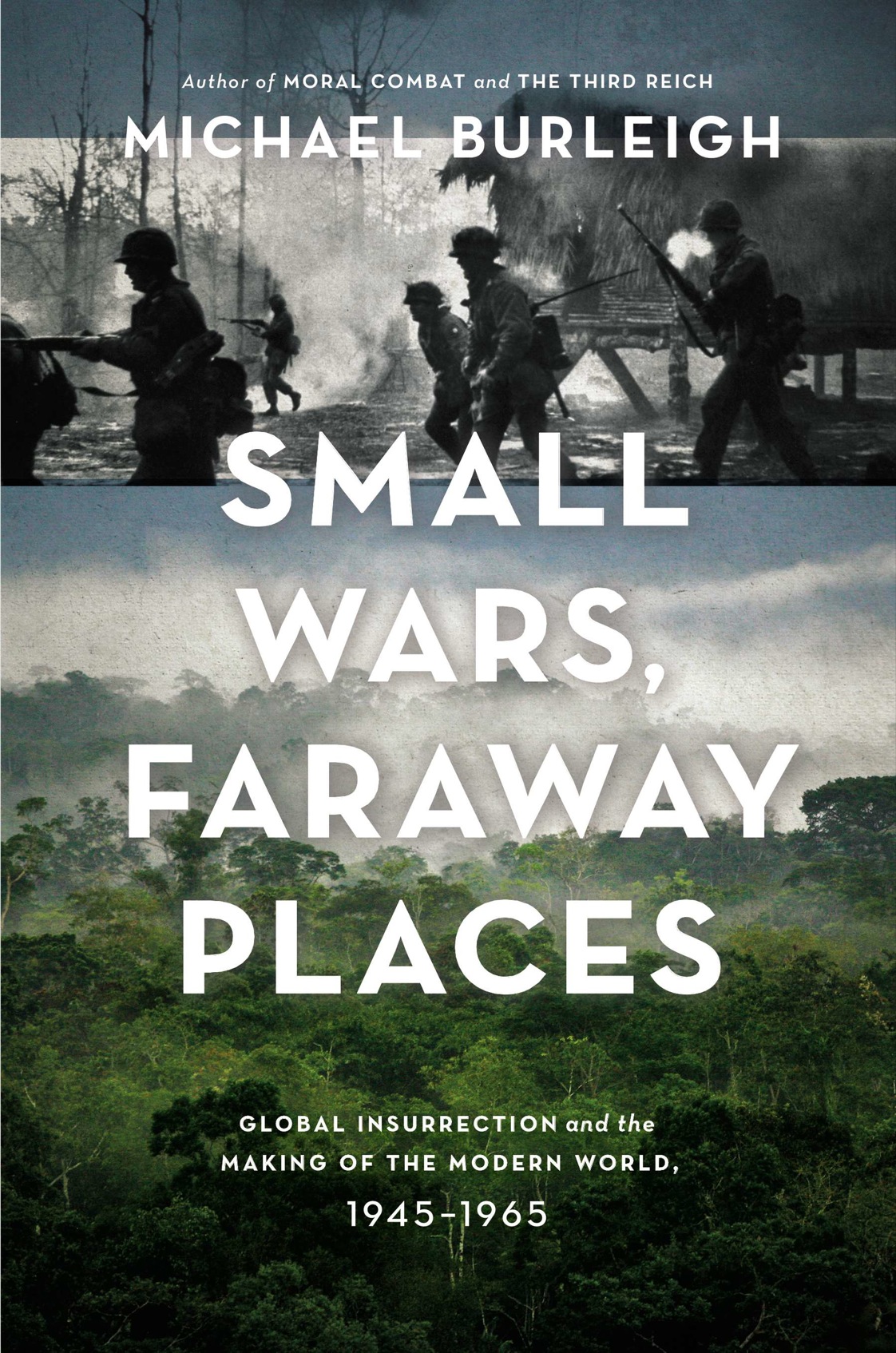

Small wars, faraway places : global insurrection and the making of the modern world, 19451965 / Michael Burleigh.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-101-63803-3

1. Low-intensity conflicts (Military science)History20th century. 2. Military history, Modern20th century. 3. United StatesMilitary policyHistory20th century. 4. World politics20th century 5. Imperialism. 6. Cold War. I. Title. II. Title: Global insurrection and the making of the modern world, 19451965.

D431.B87 2013

909.825dc23

2013017207

For Vidia and Nadira Naipaul,

Nancy Sladek and Andrea Chiari-Gaggia

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

From the Halls of Montezuma to the Green Zone of Baghdad

At the height of President George W. Bushs 2003 intervention in Iraq, bold spirits urged the United States to do as Rudyard Kipling once urged in 1899, following the lightning US conquest of the Spanish overseas empire:

Take up the White Mans burden

Send forth the best ye breed

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives need...

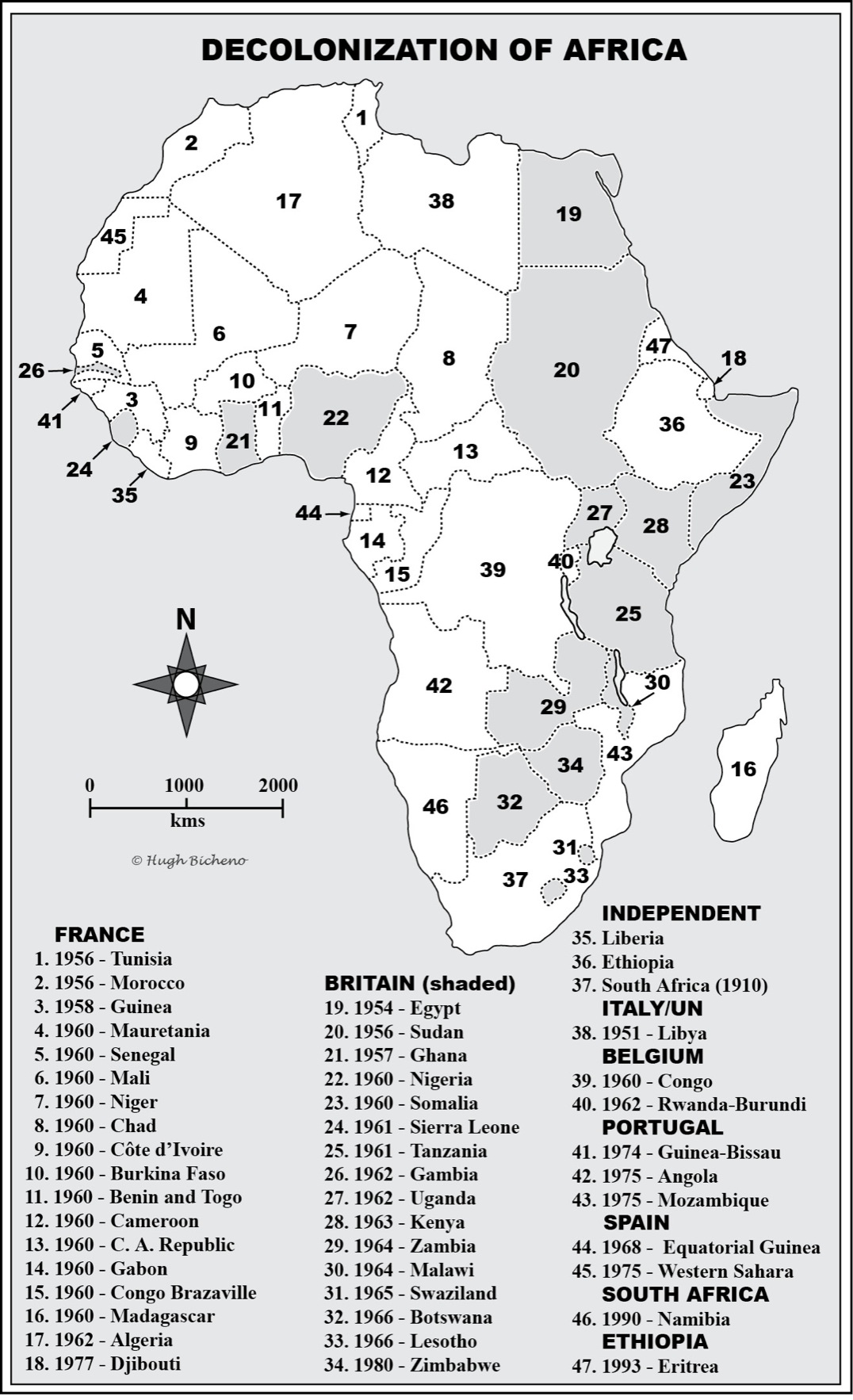

Yet in mid-1945, when the US assumed leadership of the free world, half a century after Kipling wrote and another before President Bush acted, history and tradition rendered such a choice a more equivocal affair for Americans than it is often made to seem. The pitifully needy condition of Europe after 1945, resembling the continents million wandering orphans, sealed the fate of its distant colonies. In Asia these fell like ninepins to the marauding Japanese from early 1942 onwards. The example of Nazism more generally discredited the notion that race determined political destinies, as did Imperial Japans occupation of Asia, with which this book begins.

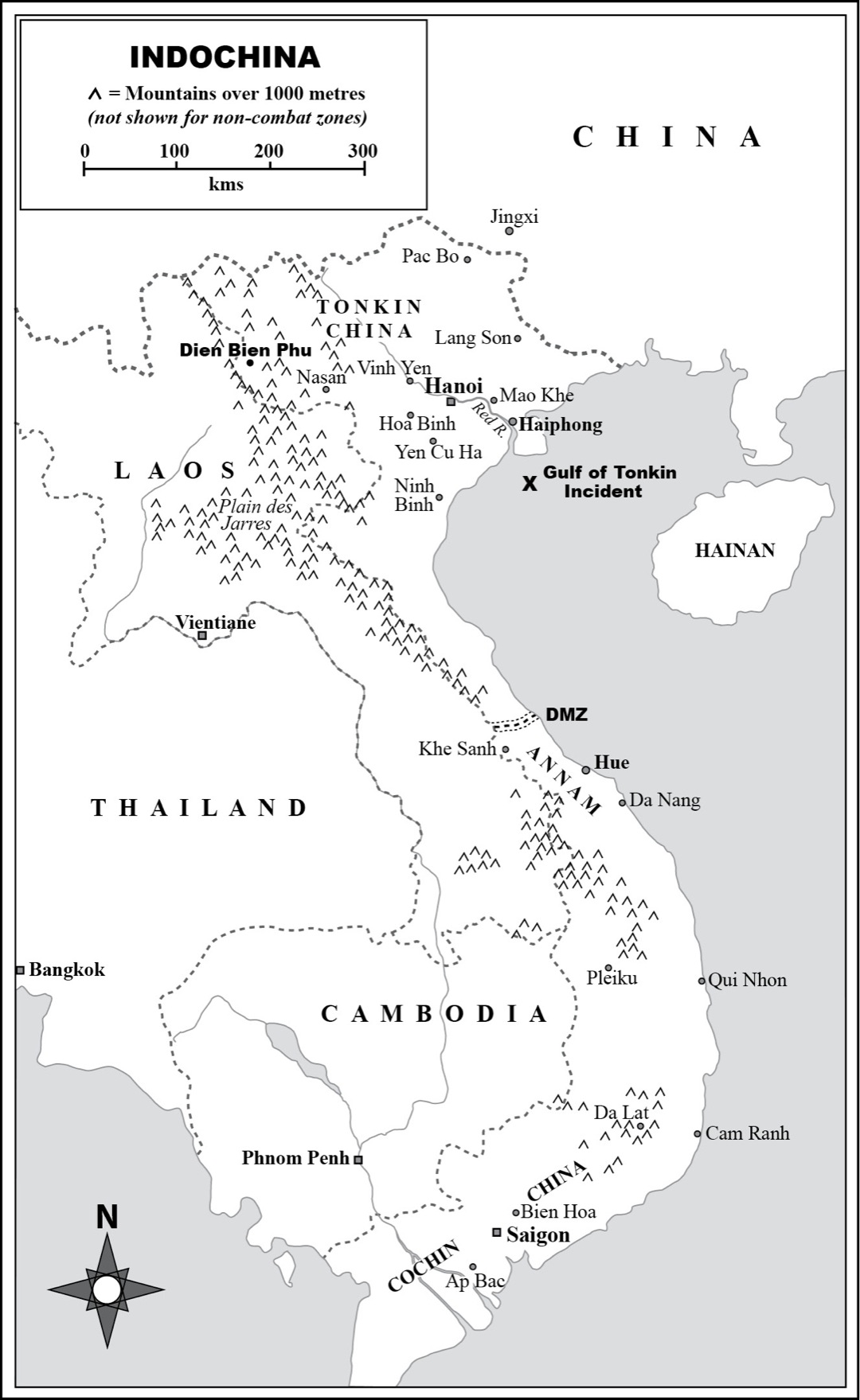

It tells the story of the eclipse of those empires, of the birth of some of the nation states that replaced them, and of how the US (and the Soviet Union) reacted to these developments. These struggles for independence, in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, coincided with the intense superpower competition called the Cold War. The Americans had to suppress a long-standing disinclination to meddle in other countries a view caricatured as isolationism and an inherent dislike of colonial rule stemming from their own freedom fight against the British. That was notwithstanding an imperialist spasm of the Republics own just before and after the dawn of the twentieth century, or intensified interference in Mexico and the Caribbean. Colonies shocked Americans, from the Presidents downwards, and despite racial segregation in the Southern states. After a wartime visit to Gambia, President Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote to his son Elliott: Dirt. Disease. Very high mortality rate. I asked. Life expectancy youd never guess what it is. Twenty-six years. These people are treated worse than livestock. Their cattle live longer! In the case of French Indochina, Roosevelt agreed with Stalin that French rule there was rotten to the core. As an article in Life magazine had it in October 1942: One thing we are sure we are not fighting for is to hold the British Empire together.

However, by the late 1940s, when the Cold War had begun in earnest, the United States calculated that propping up colonial empires was cheaper than deploying US troops, while accepting the argument that European metropolises economically weakened by decolonization would become as susceptible to Communist subversion as their colonies. Because the Soviet Union was the sole Communist state, it was assumed that its directing hand was responsible for subversion everywhere: it had after all established the Communist International, or Comintern, for that purpose in 1919. In fact, despite being Lenins former Commissar responsible for nationalities, Stalin was uninterested in the Third World. A red mist clouded the vision of Americas governing class, even when Yugoslavia and then China took another route. State Department experts also sometimes failed to detect reds under every bed and President Dwight Eisenhower warned of the dangers to democracy of a militaryindustrial complex. Of course, American inability to discriminate between Communist regimes was as nothing compared with the incapacity of successive Communist regimes to learn from the disasters of those who went before them, so that Mao repeated many of the same errors meaning murderous experiments in collectivization as Stalin, whose own radicality was eclipsed by Cambodias Pol Pot.

Not all Americans were enamoured of their new world role. US Congressmen routinely opposed any spending on new embassy buildings the State Department thought commensurate with post-war US power, because they and their constituents resented striped pants elitists bent on squandering their hard-earned cash on glass ziggurats in faraway places. Actually, foreign service officers often worked in dangerous places, where the air they breathed or the water they drank could kill them, not to speak of air travel, which was far more lethal than it is now. The resentments were reciprocal. US Secretary of State Dean Acheson, an East Coast elitist and Anglophile, once gave the game away by publicly remarking: If you truly had a democracy and did what people wanted, youd go wrong every time. That is more relevant than ever at a time when Western intervention in Afghanistan is massively unpopular in Europe and the US.